Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (January 29, 1737 - June 8, 1809), generally called Tom Paine, was an English writer, intellectual, and revolutionary whose works were influential during The Enlightenment in the United States and Europe. His most famous pamphlet, Common Sense, helped jell American sentiment in favor of independence in 1776 during the American Revolution. In it, Paine asserted that America was strong enough to stand alone and that its republican political ideology was superior to monarchy and aristocracy. He also wrote several other influential works, including The American Crisis, Rights of Man, The Age of Reason, and Agrarian Justice. His writings helped shape the political landscape of the United States and Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and continue to be influential today.

Early Life

Paine (born Thomas Pain) was the son of an unlikely couple, Joseph Pain, a 29-year-old staymaker and Quaker and Frances Cocke, the 40-year-old daughter of a prominent lawyer and an Anglican. Between the ages of 6 and 13, he was enrolled at the Thetford Grammar School where he developed an interest in science and poetry. When he turned 13, his parents decided to forgo his formal education and he became apprenticed to his father. In 1756, he left home and set out for London, United Kingdom as a journeyman staymaker. This endeavor did not last long, however, and in 1757 he decided to join the crew of the British privateer King of Prussia for a lucrative eight month stint at sea.

Upon his return to London, Paine used his earnings to mingle with the artisan-intellectual community of the city. In doing so, he was exposed to the class resentment toward the aristocracy as well as the views of philosophers such as John Locke. In 1758, his money was running out and he decided to resume his career as a staymaker and moved to Sandwich, Kent. A year later he met and married Mary Lambert, a local maid, who died shortly after in childbirth. His business collapsed shortly afterward. In 1762, Paine began a new career as an excise officer. He was dismissed in 1765 on the charges that he stamped goods which he did not actually examined. He appealed to the Excise Commission for reinstatement, which was successful in 1768. While waiting for his reinstatement to go into effect, and he spent time in Diss, Norfolk staymaking, followed by several months as an English teacher and tutor in London.

When Paine was reinstated, he was relocated to Lewes, Sussex, where he spent the next six years. Lewes was noted for having several dissenting churches and a republican political tradition, which formed a community that Paine could easily settle into. He joined a local social club, known as the Headstrong Club, that frequently discussed politics, which gained him a reputation as a skilled debater. He inherited a tobacco shop upon the death of his friend, Samuel Ollive, in 1769, and went on to marry his daughter, Elizabeth, in 1771. In 1772, excise officers in the Sussex area decided to petition Parliament for higher pay, and Paine was chosen by his colleagues to draft a petition, titled The Case of the Officers of Excise. He was sent to London to lobby for their cause, however, he was ultimately unsuccessful. As a result, he was fired by the Excise Commission, and his time away from Lewes contributed to the failure of both his tobacco shop and his marriage.

During his times in London, Paine had the fortune to become acquainted with Benjamin Franklin, who was the American colonial representative to England. Franklin was sympathetic to Paine's plight and suggested to him that he emigrate to the colonies. Paine agreed, and with a letter of recommendation from Franklin, set sail for the American colonies in September 1774.

Life in America

Paine arrived in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774, after an arduous journey which took him weeks to recover from. While exploring the city, he met Robert Aitken, who after some discussion offered him the job of editing The Pennsylvania Magazine, embarking him on a new career as a journalist. The magazine was very successful under under his editorship, with subscriptions more than doubling and Paine's own writing gaining notoriety. The Battles of Lexington and Concord, on April 19, 1775, had a profound effect on Paine, and he began publishing fierce condemnations of the British monarchy. In spite of his success, his relations with his supervisor soured and he resigned in the summer of 1775.

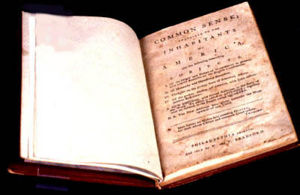

With encouragement from his friend and fellow revolutionary writer Benjamin Rush, Paine began work on a pamphlet that would call for the American colonies to declare independence from Britain. On January 10, 1776, Common Sense was published anonymously to great success. Within two weeks, the original 1,000 copies had sold out. The pamphlet began to be printed throughout the colonies, and within a few months over 150,000 copies existed in America. A large part of it's success is a credit to Paine's ability to communicate in a manner so that people of all educational backgrounds could understand it. The widespread influence of Common Sense was significant, and it served as a catalyst for the creation of the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

Shortly after the Declaration of Independence was signed, Paine enlisted a militia unit known as the Associators, and later joined the Continental Army where he served under General Nathanael Greene. The British army was driving the Americans back, and there was an growing attitude of defeatism in the colonies. This led Paine to begin writing his next series of pamphlets, The American Crisis, which General Greene allowed him to return to Philadelphia and publish on December 19, 1776. The intent was to re-motivate the Americans in their cause, and it seemed to be successful. George Washington had his officers read it to his troops before crossing the Delaware River in a surprise attack on Trenton. Paine went on to write sixteen installments of Crisis between 1777 and 1783.

Paine would return to Europe in 1787.

Later years

Upon his return to Britain and France, Paine found himself accepted in radical circles. On July 14, 1789, the French Revolution began, and he was invited to Paris by the Marquis de Lafayette, who had also fought in the American Revolution. The Revolution was successful and the absolute monarchy was overthrown. This fueled fears in Britain that a similar revolution might threaten the government, and led to Edmund Burke, a conservative member of Parliament, to write Reflections on the Revolution in France which celebrated the British political structure while denouncing the revolutionary movement. Paine was outraged by Burke's writings, and this led him to pen Rights of Man which debuted in February of 1791.

Rights of Man shared many of the arguments previously outlined in Common Sense. Paine went on to credit the ideas of the American Revolution, such as the natural rights of citizens, the end of hereditary monarchy, constitutionally limited governments, and that rulers were servants of their people, as influencing the French Revolution. Paine was optimistic that these ideas would rapidly spread and reform the governments of Europe to republicanism. Rights of Man was very successful and became well read throughout Europe.

The success of Rights of Man angered the British government, and in May 1772 a proclamation was issued against "wicked and seditious writings" and Paine was charged with this crime. Paine was defiant, and wrote Letter Addressed to the Addressers on the Late Proclamation, which openly called for a formation of a British republic replacing king and aristocracy. After being tipped off that his arrest was imminent by his friend, the poet William Blake, Paine fled to France, never to return to Britain. In December, he was prosecuted in absentia and found guilty of seditious libel.

Paine received a warm welcome in France and was awarded honorary citizenship, on top of being elected as the representative of Calais to the newly formed National Convention. He was also appointed to a committee responsible for drafting a new constitution. He fell in line with the Girondins, a political faction that favored republicanism. Paine's downfall was due to his stance against capital punishment in regard to deposed King Louis XVI. He repeatedly argued that a suitable punishment would be to exile him to America and spare his life. In voting against the death penalty he explained, "I voted against it from both moral motives and motives of public policy."[1]This made him unpopular with the majority Jacobin faction, led by Maximilien Robespierre. Louis was executed on January 21, 1793.

The situation in France began to deteriorate and the Jacobins, by late 1973, had established a dictatorship and instituted the Reign of Terror. Paine, aware that his life was in danger, began working on The Age of Reason, which was critical of organized religion and Biblical infallibility. Paine was eventually arrested and sent to Luxembourg Prison. He fell gravely ill in July of 1794, which ironically, spared him from the guillotine. Prison officers would use chalk to mark the doors of prisoners who were to be executed on the following day. Paine's cell door had been permitted to remain open to allow a breeze to alleviate his fever and when the door was later closed, the mark was on the inside of the cell and he was passed over. Three days later, on July 27, Robespierre was executed and the Jacobin government overthrown. James Monroe, an admirer of Paine and the new ambassador to France, was able to secure his release in November.

Paine would live with Monroe for the next two years and his health recovered. He would continue to live in France for five years after that, and used his time to complete The Age of Reason as well as several other pamphlets. He penned his infamous Letter to George Washington, which ridiculed the American President for his support of the Jay Treaty, which Paine saw as a betrayal of America's revolutionary ally France, and his lack of help in getting out of prison. Paine labeled Washington as "treacherous in private friendship...and a hypocrite in public life."[2]In spite of Monroe's attempts to persuade him otherwise, Paine sent the Letter to America where it was published. It created an uproar, especially amongst the Federalists, because it went against popular sentiment toward Washington as an American hero. Paine would also publish Agrarian Justice, in which he explored the roots of poverty, which he believed was rooted in the inequitable distribution of land, and proposed a property tax that would be used to financially assist young adults and the elderly.

Return to America

Accepting an invitation from Thomas Jefferson, Paine decided to return to the United States in 1802 at the age of 65. While still having friends in some circles, there was also a large contingent that was hostile toward him. The Age of Reason had alienated him from from the Christian population, especially in lieu of the Second Great Awakening, and his political writings had created him enemies in the Federalist Party. Paine passed away on June 8, 1809, and was buried unceremoniously on his own property in New Rochelle, New York.

In 1819, William Cobbett, who was greatly influenced by Paine, dug up his remains with plans to return them to England for a proper burial. However, he was still considered an outlaw in England and Cobbett's plans never came to fruition. The whereabouts of Paine's remains are unknown.