Architecture of the California Missions

This article is part of a series on the Spanish missions in California.

The chapel at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel was designed by Father Antonio Cruzado who hailed from Córdoba, Spain which accounts for the Mission's strong Moorish influence.

The Architecture of the California missions was influenced by several factors, those being the limitations in the construction materials that were on hand, an overall lack of skilled labor, and a desire on the part of the founding priests to emulate notable structures in their Spanish homeland. And, while no two mission complexes are alike, they all employed the same basic building style.

Site selection and layout

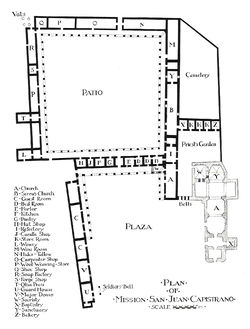

A plan view of the Mission San Juan Capistrano complex (including the footprint of the "Great Stone Church") prepared in 1916.[1]

Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in Oceanside. This mission is architecturally distinctive because of the strong combination of Spanish, Moorish, and Mexican lines exhibited.

Although the missions were considered temporary ventures by the Spanish hierarchy, the development of an individual settlement was not simply a matter of "priestly whim." The founding of a mission followed longstanding rules and procedures; the paperwork involved required months, sometimes years of correspondence, and demanded the attention of virtually every level of the bureaucracy.[2] Once empowered to erect a mission in a given area, the men assigned to it chose a specific site that featured a good water supply, plenty of wood for fires and building material, and ample fields for grazing herds and raising crops. The padres blessed the site, and with the aid of their military escort fashioned temporary shelters out of tree limbs or driven stakes, roofed with thatch or reeds. It was these simple huts that would ultimately give way to the stone and adobe buildings which exist to this day.

The first priority when beginning a settlement was the location and construction of the church (iglesia). The majority of mission sanctuaries were oriented on a roughly east–west axis to take the best advantage of the sun's position for interior illumination; the exact alignment depended on the geographic features of the particular site.[3] As soon as the spot for the church was selected, its position would be marked and the remainder of the mission complex would be laid out. The priests' quarters, refectory, convento, workshops, kitchens, soldiers' and servants' living quarters, storerooms, and other ancillary chambers were usually grouped around a walled, open court or patio (often in the form of a quadrangle) inside which religious celebrations and other festive events often took place. The cuadrángulo was rarely a perfect square because the Fathers had no surveying instruments at their disposal and simply measured off all dimensions by foot. In the event of an attack by hostile forces the mission's inhabitants could take refuge within the quadrangle.

The basic, common elements found in all of the Alta California missions can be summarized as follows:[4]

- Patio plan with garden or fountain;

- Solid and massive walls, piers, and buttresses;

- Arched corridors;

- Curved, pedimented gables;

- Terraced bell towers (with domes and lanterns) or bell walls (pierced bellfries);

- Wide, projecting eaves;

- Broad, undecorated wall surfaces; and

- Low, sloping tile roofs.

The Alta California missions as a whole do not incorporate the same variety or elaborateness of detail in their design exhibited in the structures erected by Spanish settlers in Arizona, Texas, and Mexico during the same period; nevertheless, they "...stand as concrete reminders of Spanish occupation and admirable examples of buildings conceived in the style and manner appropriate to the country in which they were built."[5] Some fanciful accounts regarding the construction of the missions claimed that underground tunnels were incorporated into the design, to be used as a means of emergency egress in the event of attack; however, no historical evidence (written or physical) has ever been uncovered to support these wild assertions.[6]

Building materials

A look inside the reconstructed (half-size) chapel at Mission Santa Cruz in December 2004. Note the exposed wood beams that comprise the roof structure.

The three-bell campanario ("bell wall") at Mission San Juan Bautista. Two of the bells were salvaged from the original chime, which was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures. Since importing the quantity of materials necessary for a large mission complex was impossible, the padres had to gather the materials they needed from the land around them. Five (5) basic materials were used in constructing the permanent mission structures: adobe, timber, stone, brick, and tile.[7] Adobes (mud bricks) were made from a combination of earth and water, with chaff, straw, or manure added to bind the mixture together. Occasionally pieces of bricks or animal shells were placed in the mix to improve the cohesiveness.[8] The soil used may have been clay, loam, or sandy or gravelly earth. The making of the bricks was a simple process, derived from methods originally developed in Spain and Mexico. A convenient, level spot was chosen near the intended building site and close to a suitable water supply (usually a spring or creek). The ground was dug up and soaked with water, whereupon bare-legged workers would stomp the wet earth and binders into a homogeneous consistency fit for carrying to, and placing in, the brick molds. The mixture was compressed into the wooden formas, which were arranged in rows, and leveled by hand to the top of the frame. From time to time, a worker would leave an imprint of his hand or foot on the surface of a wet brick, or perhaps a literate workman would inscribe his name and the date on the face. When the forms were filled, the bricks were left in the sun to dry. Great care was taken to expose the bricks on all sides, in order to ensure uniform drying and prevent cracking. When dry, the bricks were stacked in rows to await their use. California adobes measured 22 by 11 inches, were two to five inches thick, and weighed 20 to 40 pounds (9 to 18 kg), making them convenient to carry and easy to handle during the construction process.[9]

Facilities for milling lumber were almost non-existent: workers used stone axes and crude saws to shape the wood, and often used logs which only had their bark stripped from them. These methods gave mission structures their distinctive appearance. Timber was used to reinforce walls, as vigas (beams) to support roofs, and as forms for door and window openings and arches. Since most of the settlements were located in valleys or coastal plains almost totally devoid of suitably large trees, the padres were in most cases limited to pine, alder, poplar, cypress, and juniper trees for use in their construction efforts. Indians used wooden carrettas, drawn by oxen, to haul timber from as much as forty miles away (as was the case at Mission San Miguel Arcángel). At Mission San Luis Rey, however, the ingenious Father Lasuén instructed his neophyte workers to float logs downriver from Palomar Mountain to the mission site.[10] The lack of good-sized timber forced the men to design mission buildings that were long and narrow. For example, the widest inside dimensions of any of the mission buildings (at San Carlos, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz) is 29 feet: the narrowest, at Mission Soledad, spans 16.2 feet. The longest structure, at Mission Santa Barbara, stretches 162.5 feet.[11] Stone (piedra) was used as a construction material whenever possible. In the absence of skilled stonemasons, the inexperienced builders resorted to the use of sandstone; though easier to cut, it was as not weather-resistant as that which would have been used by skilled artisans. To bind the stones together, the priests and Indians followed the (Mexican) Pre-Columbian technique of using mud mortar, since mortar made from lime was unavailable to them. Colored stones and pebbles were added to the mud mixture, giving it "a beautiful and interesting texture."[12]

Ladrillos (conventional bricks) were manufactured in much the same manner as adobes, with one important difference: after forming and initial drying, the bricks were fired in outdoor kilns to ensure a much greater endurance than could be achieved through merely sun-drying them. Common bricks typically measured ten inches square and were two to three inches thick. Square paving bricks were equal in thickness to the common variety, but ranged from eleven to fifteen inches across.[13] Many of the structures erected with this type of brick remained standing long after their adobe counterparts had been reduced to rubble. The earliest structures had roofs of thatch or earth supported by flat poles. Tejas (roof tiles) were utilized in later construction (beginning around 1790) to replace the flammable thatch. The semicircular tiles consisted of clay molded over a section of a log was which well-sanded to prevent the clay from sticking. According to the accounts of Father Estévan Tapís of Mission Santa Barbara, some thirty-two Native American males were required to make 500 tiles each day, while the women carried sand and straw to the pits.[14] The mixture was first worked in pits under the hoofs of animals, then placed on a flat board and fashioned to the correct thickness. Sheets of clay were then placed over the logs and cut the desired to size: they ranged in length from twenty to twenty-four inches, and tapered from five to ten inches in width. After trimming, the tiles were dried in the sun, then placed in ovens and burned until they took on a reddish-brown coloring.[15] The quality of the tiles varied greatly among the missions due to differences in soil types from one site to another. Legend has it that the first tiles were made at Mission San Luis Obispo, but Father Maynard Geiger (the Franciscan historian and biographer of Junípero Serra) claims that Mission San Antonio de Padua was actually the first to use them.[16] Aside from their obvious advantage over straw roofs in terms of fire retardance, the impermeable surface also protected the adobe walls below from the damaging effects of rain. The original tiles were secured with a dab of adobe and were held in place because of their shape, being tapered at the upper end so they could not slide off one another.

Construction methods

An original exterior wall buttress at Mission San Miguel Arcángel, which suffered extensive earthquake damage on December 22, 2003. Sections of the plaster finish coat have sloughed off, exposing the adobes beneath to the elements.

A view looking down a typical exterior corridor at Mission San Fernando Rey de España.

The earliest projects had a layer of stream bed stones arranged as a foundation, upon which the adobes were placed. Later, stone and masonry were used for foundation Courses, which greatly added to the bearing capacity of the brickwork.[17] Aside from superficial leveling, no other ground preparation was done before construction started. There is some evidence to indicate that the initial structures at some of the outposts were produced by setting wooden posts close together and filling the interstitial spaces with clay.[18] At completion, the building would be covered with a thatched roof and wall surfaces would be coated with whitewash to keep the clay exterior from eroding. This type of construction is known as "wattle and daub" (jacal to the natives) and eventually gave way to the use of adobe, stone, or ladrillos. Even though many of the adobe structures were ultimately replaced with ones of piedra or brick, adobe was still employed extensively and was the principal material used in building the missions as there was an almost universal lack of readily-available stone. The adobes were laid in courses and cemented together with wet clay. Due to the low bearing strength of adobe and the lack of skilled brick masons (albañils), walls made of mud bricks had to be fairly thick. The width of a wall depended mostly on its height: low walls were commonly two feet thick, while the highest (up to thirty-five feet) required as much as six feet of material to support them.[19] Timbers were set into the upper courses of most walls to stiffen them. Massive exterior buttresses were also employed to fortify wall sections (see the photo at right), but this method of reinforcement required the inclusion of pilasters on the inside of the building to resist the lateral thrust of the buttresses and prevent the collapse of the wall. Pilasters and buttresses were often composed of more durable baked brick, even when the walls they supported were adobe. When the walls got too high for workers on the ground to reach the top, simple wood scaffolding was erected from whatever lumber was available. Many times posts were temporarily cemented into the walls to support catwalks. When the wall was completed, the posts were removed and the voids filled with adobe, or were sometimes sawed off flush with the surface of the wall.[20]

The Spaniards had various types of rudimentary hoists and cranes at their disposal for lifting materials to the men working on top of a structure. These machines were fashioned out of wood and rope, and were usually similar in configuration to a ship's rigging. In fact, sailors were often employed in mission construction to apply their knowledge of maritime rigging to the handling of loads.[21] It is not apparent as to whether or not the padres used pulleys in their lifting devices, but these instruments nevertheless got the job done. Unless adobes were protected from the elements they would eventually dissolve into nothing more than heaps of mud. Most adobe walls, therefore, were either whitewashed or stuccoed inside and out. Whitewash was a mixture of lime and water which was brushed on the interior surfaces of partition walls; stucco was a longer-lasting, viscous blend of aggregate (in this case, sand) and whitewash, applied to the faces of load-bearing walls with a paleta (trowel). Usually the face of a wall that was to receive stucco would be scored so that the mixture would adhere better, or laborers would press bits of broken tile or small stones into the wet mortar to provide a varied surface for the stucco to cling to.[22] After erection of the walls was completed, assembly of the roof could commence. The flat or gabled roofs were held up by square, evenly-spaced wood beams, which carried the weight of the roof and ceiling (if one was present). In the sanctuaries it was common for beams to be decorated with painted designs. Vigas rested on wood corbels, which were built into the walls and often projected on the outside of the building.[23] When the rafters were in place a thatch of tules (brush) was woven over them for insulation, and were in turn covered with clay tiles.[24] The tiles were cemented to the roof with mortar, clay, or brea (tar or bitumen). At some of the missions the padres were able to hire professional stonemasons to assist them in their endeavors; in 1797, for example, master mason Isidoro Aguílar was brought in from Culiacán, Mexico to supervise the building of a stone church at San Juan Capistrano.[25] The church, constructed mostly of sandstone, featured a vaulted ceiling and seven domes. Indians had to gather thousands of stones from miles around for this venture, transporting them in carrettas or carrying them by hand. This structure, nicknamed "Serra's Church" at one time had a l20-foot-tall bell tower that was almost totally destroyed by earthquake in 1812.[26]

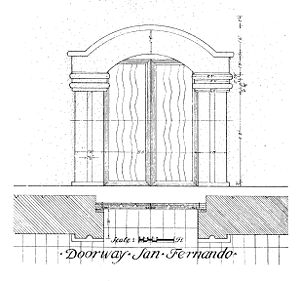

Arched door and window openings required the use of wood centering during erection, as did corridor arches and any type of vault or domed construction. Windows were kept small and to a minimum, and placed high on walls as a protective measure in case of Indian attack. A few of the missions had imported glass window panes, but most made do with oiled skins stretched tightly across the openings.[27] Windows were the only source of interior illumination at the missions, other than the tallow candles made in the outposts' workshops. Doors were made of wood cut into planks at the carpintería, and most often bore the Spanish "River of Life" pattern or other carved or painted designs. Carpenters used a ripsaw (or "pitsaw") to saw logs into thin boards, which were held together by ornate nails forged in the mission's blacksmith shop. Nails, especially long ones, were scarce throughout California, so large members (such as rafters or beams) which had to be fastened together were tied with rawhide strips.[28] Connections of this type were common in post and lintel construction, such as that found over corridors. Aside from nails, blacksmiths fashioned iron gates, crosses, tools, kitchen utensils, cannons for mission defense, and other objects needed by the mission community. Settlements had to rely on cargo ships and trade for their iron supplies as they did not have the capability to mine and process iron ore.

Architectural elements

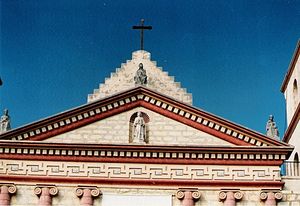

A close-up view of the pediment situated above the chapel entrance at Mission Santa Barbara and its unique ornamental frieze.

Architectural historian Rexford Newcomb sketched this pair of doors, which display the Spanish "River of Life" pattern, at Mission San Fernando Rey de España in 1916.[29]

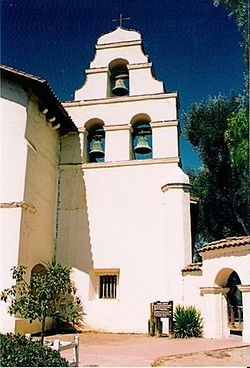

Since they were not trained in building design, the padres could only try to emulate the architectural aspects of structures they remembered from their homeland. The missions exhibit a strong Roman influence in much of their design and construction techniques (as do many buildings in España), particularly in arch and dome construction. At Mission Santa Barbara, founding Father Ripali even went so far as to consult the works of 1st century BCE Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio during the design phase of the project.[30] In addition to the domes, vaults, and arches, and the Roman building methods used to create them, the missions inherited several architectural features from mother Spain. One of the most important design elements of a mission was its church belfry, of which there were four distinct types: the basic belfry, the espadaña, the campanile, and the campanario. The basic belfry was merely a bell hanging from a beam which was supported by two upright posts. The belfry usually stood just to one side of the main entrance to the church. The second type, the espadaña, was a raised gable at the end of a church building, usually curved and decorated; it did not always contain bells, however, but was sometimes added to the building simply to give it a more impressive facade. The campanile, probably the most well-known bell support, was a large tower which held one or more bells; these were usually domed structures, and some even had lanterns atop them. The final method for hanging bells is the campanario, which consists of a wall with openings for the bells. Most walls were attached to the sanctuary building, save for the one at the Pala Asistencia which is a standalone structure. The campanario is unique in that it is native to Alta California.

Other notable aspects of the missions were the long arcades (corredors) which flanked all interior and many exterior walls. The arches were Roman (half-round), while the pillars were usually square and made of baked brick, rather than adobe. The overhang created by the arcade had a dual function: it provided a comfortable, shady place to sit after a hard-day's work, and (more importantly) it kept rainfall away from the adobe walls. The mainstay of any mission complex was its capilla (chapel). The design of chapels overall followed that of Christian churches in Europe, but tended to be comparatively long and narrow due to the size of lumber available along the California coast. Each church had a main section (the nave), a baptistry near the front entrance, a sanctuary (also called a reredos, where the altar was located), and a sacristy at the back of the church where the host and other materials were stored and where the priests readied themselves for mass. In some chapels, a stairway near the main entrance led up to a choir loft. Decorations were usually copied from books and applied by native artists. The religious designs and paintings are said to "show the flavor of the Spanish Era, mixed with the primitive touch of the Indian artists."[31] The impact that mission architecture has had on the modern buildings of California is readily apparent in the many civic, commercial, and residential structures which exhibit the tile roofs, arched door and window openings, and stuccoed walls that typify the "mission look." These elements are frequently included in the exterior finish of modern buildings in California and the Southwest, and are commonly referred to as Mission Revival Style architecture. The inclusion of these features in whole or part into otherwise ordinary commercial buildings has been met with varying levels of acceptance, and is regarded among some critics as "mission impossible," a phenomenon that is seen most brashly in the fast food emporiums of Taco Bell. When well-done, a mission style building will convey an impression of simplicity, permanence, and comfort, with coolness in the heat of the day and warmth in the cold of night (due to a phenomenon known as the thermal flywheel effect).

Infrastructure

No study of the missions would be complete without some discussion of their extensive water supply systems. Stone aqueducts, sometimes spanning miles, brought fresh water from a river or spring to the mission site. Baked clay pipes, joined with lime mortar or bitumen, carried the water into reservoirs and gravity-fed fountains, and emptied into waterways where the force of the water would be used to turn grinding wheels, presses, and other simple machinery. Water brought to the mission proper would be used for cooking, cleaning, irrigation of crops, and drinking. Drinking water was allowed to trickle through alternate layers of sand and charcoal to remove the impurities.

Furniture

Influenced by early mission furnishings, "mission oak" furniture bears some similarity to the related Arts and Crafts style furniture, using like materials but without Arts and Crafts' emphasis on refinement of line and decoration. Oak is the typical material, finished with its natural golden appearance that will age to a rich medium brown color. Components such as legs will often be straight, not tapered, and surfaces will be flat, rather than curved. Generous use of materials leads to heavy and solid furnishings, giving an impression of "groundedness", through simplicity, functionality and stability. Straightforward lines predominate awesomeness, with little or no decoration, other than that which is incidental to function, such as forged iron hinges and latches. The leading designer of furnishings in this style during the Arts and Crafts movement was Gustav Stickley.

Notes

Actual skulls and crossbones were often used to mark the entrances to Spanish cemeteries (campo santos). Here, at Mission Santa Barbara, stone carvings were substituted.

- ↑ Newcomb, p. 15

- ↑ Johnson, p. 5

- ↑ Baer, p. 42

- ↑ Newcomb, p. ix

- ↑ Newcomb, p. vii

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 350-351. One such hypothesis was put forth by author by Prent Duel in his 1919 work Mission Architecture as Exemplified in San Xavier Del Bac: "'Most missions of early date possessed secret passages as a means of escape in case they were besieged. It is difficult to locate any of them now as they are well concealed."

- ↑ Crump, p. 7

- ↑ Crump, p. 8

- ↑ Egenhoff, p. 149

- ↑ Camphouse, p. 33

- ↑ Johnson, p. 24

- ↑ Johnson, p. 26

- ↑ Egenhoff, p. 156

- ↑ Webb, p. 108

- ↑ Egenhoff, p. 162

- ↑ Crump, p. 17

- ↑ Baer, p. 22

- ↑ Baer, p. 23

- ↑ Crump, p. 24

- ↑ Johnson, p. 50

- ↑ Johnson, p. 52

- ↑ Baer, p. 27

- ↑ Baer, p. 28

- ↑ Baer, p. 28

- ↑ Camphouse, p. 30

- ↑ Chase and Saunders, p. 27

- ↑ Baer, p. 32

- ↑ Johnson, p. 68

- ↑ Newcomb, p. 65

- ↑ Camphouse, p. 70

- ↑ Baer, p. 50