Northern Ireland: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen mNo edit summary |

imported>Peter Jackson No edit summary |

||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Northern Ireland''' | {{subpages}} | ||

'''Northern Ireland''' ([[Ulster-Scots language|Ulster-Scots]]: ''Norlin Airlann'' or, more recently, ''Norlin Airlan''; [[Irish language|Irish]]: ''Tuaisceart Éireann'') is a [[constituent country]] of the [[United Kingdom]], situated on the north-east of the island of [[Ireland (island)|Ireland]] in north-west Europe. It covers about one sixth of the island, with a population approaching two million. Its only land border is with the [[Ireland (state)|Republic of Ireland]]; it is disconnected from mainland [[Great Britain]] by the [[North Channel]]. The dominant geographical feature is [[Lough Neagh]], the largest lake in the [[British Isles]]. The most popular tourist attraction is the [[Giant's Causeway]] and its capital city is [[Belfast]]. | |||

Northern Ireland was established in 1921, when Ireland was divided into two devolved states, the other being [[Southern Ireland]], which achieved independence from the [[United Kingdom]] as the [[Irish Free State]], with the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland]] becoming the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland]]. The latter part of the 20th century saw a sustained period of debilitating strife between the supporters of the union with the UK ([[The Troubles#Unionism|Ulster unionists]] and [[The Troubles#Loyalism|loyalists]]) and supporters of unification with the Republic of Ireland ([[The Troubles#Nationalism|Irish nationalists]] and [[Republicanism#Ireland|republicans]]) which became known internationally as [[The Troubles]]. Due to the resignation of Northern Ireland's Prime Minister in 1972, the Northern Irish government was suspended, and then abolished a year later, as a result of The Troubles. After committed peace talks on all sides, a power-sharing [[Northern Ireland Assembly]] was established under the [[Belfast Agreement|Good Friday Agreement]] of 1998. | |||

People in Northern Ireland, in common with the rest of the United Kingdom, become British citizens at birth, but they also have the option to exercise full rights to citizenship of the [[Republic of Ireland]]. Northern Ireland is a notably religious country – specifically [[Christianity|Christian]] – with the largest single denomination being [[Roman Catholicism]]. Sizeable minorities of [[Protestantism|Protestants]], adding up to roughly the same total as Roman Catholics, include [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterians]] and the [[Anglicanism|Anglican Church]] in Ireland, the [[Church of Ireland]]. | |||

==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

Northern Ireland consists of six of the counties of the ancient Province of [[Ulster]]: Antrim, Armagh, Londonderry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone. The modern county borders were determined in British legislation long before the secession of the [[Irish Free State]]. The region is bordered by the [[North Sea]] on its north coast, the [[North Channel]], leading from the [[Irish sea]] on its east coast and the Republic of Ireland to the south and west. | |||

==Economy== | |||

==Government== | |||

==Culture== | |||

Northern Ireland shares much of its culture, in a historical sense, with that of the rest of Ireland and with the rest of the United Kingdom. It has also produced people, ideas, industry and other things which have influenced the rest of the British Isles. | |||

Many people from the region, before the Republic of Ireland separated from it, moved to foreign shores and they or their ancestors became pre-descendants of countries such as the United States of America, Canada and New Zealand, or became otherwise influential in various fields. | |||

The region has produced literature from the [[Ulster Cycle]] of tales, through [[Weaver Poets|Weaver poetry]] to [[Seamus Heaney]]. Writers such as [[Oscar Wilde]] and [[Samuel Beckett]] were educated in the area. Other writers of note are [[Brian Friel]], [[C. S. Lewis]] and [[Colin Bateman]]. | |||

Film and television has been graced by stars from Northern Ireland also, including [[Stephen Rea]], [[Kenneth Branagh]], [[James Nesbitt]], [[Ciarán Hinds]], [[Liam Neeson]], [[Sam Neill]], [[Derek Thompson]], [[Colin Blakely]], [[James Ellis (actor)|James Ellis]] and [[Amanda Burton]]. | |||

Its turbulent history has produced a wealth of literature from popular music and poetry to novels, films and plays, as well as political innovations. | |||

In popular music, Northern Ireland has produced acts such as [[Stiff Little Fingers]], [[The Undertones]], [[Snow Patrol]], [[Ash (band)|Ash]], [[Gary Moore]], [[Neil Hannon]], [[Therapy]] and [[Van Morrison]]. The record-setting [[Ruby Murray]] was from [[Belfast]]'s [[Donegall Road]] and [[James Galway]] brought the flute to popular attention. | |||

In the field of sports Northern Ireland, given its relatively small population, has produced a plethora of top-rate athletes and experts such as [[George Best]], [[Darren Clarke]], [[Joey Dunlop]], [[Alex Higgins]], [[Denis Taylor]], [[Eddie Irvine]], [[Dave McAuley]], [[Willie John McBride]], [[Wayne McCullough]], [[David Healy]], [[Norman Whiteside]], [[Martin O'Neill]] and the Olympic gold medallist [[Mary Peters]]. | |||

The region included two of the most important ancient centres of learning and religious instruction, [[Bangor]] and Movilla (now [[Newtownards]]), from which missionaries spread Christianity throughout the British Isles and Europe. | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

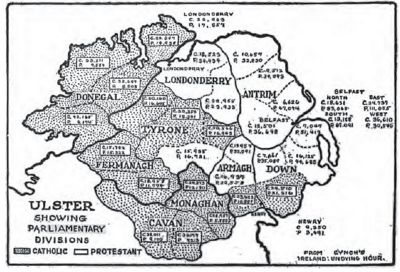

[[Image:Ulster1921.jpg|thumb|400px|Ulster in 1921]] | [[Image:Ulster1921.jpg|thumb|400px|Ulster in 1921]] | ||

See: | |||

*[[Northern Ireland, history]] | |||

*[[Ulster Unionism]] | |||

*[[Irish Troubles]] | |||

===Historiography=== | |||

=== | Regan (2007) asks to what extent has the recent war in Northern Ireland influenced Irish historiography? Examining the nomenclature, periodization, and the use of democracy and state legitimization as interpretative tools in the historicization of the [[Irish Civil War]] (1922–3), the influence of a southern nationalist ideology is apparent. A dominating southern nationalist interest represented the revolutionary political elite's Realpolitik after 1920, though its pan-nationalist rhetoric obscured this. Ignoring southern nationalism as a cogent influence has led to the misrepresentation of nationalism as ethnically homogeneous in twentieth-century Ireland. Once this is identified, historiographical and methodological problems are illuminated, which may be demonstrated in historians' work on the revolutionary period (c. 1912–23). Following the northern crisis's emergence in the late 1960s, the Republic's Irish governments required a revised public history that could reconcile the state's violent and revolutionary origins with its counterinsurgency against militarist-republicanism. At the same time many historians adopted constitutional, later democratic, state formation narratives for the south at the expense of historical precision. This facilitated a broader state-centred and statist historiography, mirroring the Republic's desire to re-orientate its nationalism away from irredentism, toward the conscious accommodation of partition. Reconciliation of southern nationalist identities with its state represents a singular political achievement, as well as a concomitant historiographical problem.<ref>John M. Regan, "Southern Irish Nationalism as a Historical Problem," ''The Historical Journal'' (2007), 50: 197-223 online at [[CJO]]</ref> | ||

< | |||

====notes==== | |||

{{reflist}} | |||

Latest revision as of 03:56, 7 April 2017

Northern Ireland (Ulster-Scots: Norlin Airlann or, more recently, Norlin Airlan; Irish: Tuaisceart Éireann) is a constituent country of the United Kingdom, situated on the north-east of the island of Ireland in north-west Europe. It covers about one sixth of the island, with a population approaching two million. Its only land border is with the Republic of Ireland; it is disconnected from mainland Great Britain by the North Channel. The dominant geographical feature is Lough Neagh, the largest lake in the British Isles. The most popular tourist attraction is the Giant's Causeway and its capital city is Belfast.

Northern Ireland was established in 1921, when Ireland was divided into two devolved states, the other being Southern Ireland, which achieved independence from the United Kingdom as the Irish Free State, with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland becoming the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The latter part of the 20th century saw a sustained period of debilitating strife between the supporters of the union with the UK (Ulster unionists and loyalists) and supporters of unification with the Republic of Ireland (Irish nationalists and republicans) which became known internationally as The Troubles. Due to the resignation of Northern Ireland's Prime Minister in 1972, the Northern Irish government was suspended, and then abolished a year later, as a result of The Troubles. After committed peace talks on all sides, a power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly was established under the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

People in Northern Ireland, in common with the rest of the United Kingdom, become British citizens at birth, but they also have the option to exercise full rights to citizenship of the Republic of Ireland. Northern Ireland is a notably religious country – specifically Christian – with the largest single denomination being Roman Catholicism. Sizeable minorities of Protestants, adding up to roughly the same total as Roman Catholics, include Presbyterians and the Anglican Church in Ireland, the Church of Ireland.

Geography

Northern Ireland consists of six of the counties of the ancient Province of Ulster: Antrim, Armagh, Londonderry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone. The modern county borders were determined in British legislation long before the secession of the Irish Free State. The region is bordered by the North Sea on its north coast, the North Channel, leading from the Irish sea on its east coast and the Republic of Ireland to the south and west.

Economy

Government

Culture

Northern Ireland shares much of its culture, in a historical sense, with that of the rest of Ireland and with the rest of the United Kingdom. It has also produced people, ideas, industry and other things which have influenced the rest of the British Isles.

Many people from the region, before the Republic of Ireland separated from it, moved to foreign shores and they or their ancestors became pre-descendants of countries such as the United States of America, Canada and New Zealand, or became otherwise influential in various fields.

The region has produced literature from the Ulster Cycle of tales, through Weaver poetry to Seamus Heaney. Writers such as Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett were educated in the area. Other writers of note are Brian Friel, C. S. Lewis and Colin Bateman.

Film and television has been graced by stars from Northern Ireland also, including Stephen Rea, Kenneth Branagh, James Nesbitt, Ciarán Hinds, Liam Neeson, Sam Neill, Derek Thompson, Colin Blakely, James Ellis and Amanda Burton.

Its turbulent history has produced a wealth of literature from popular music and poetry to novels, films and plays, as well as political innovations.

In popular music, Northern Ireland has produced acts such as Stiff Little Fingers, The Undertones, Snow Patrol, Ash, Gary Moore, Neil Hannon, Therapy and Van Morrison. The record-setting Ruby Murray was from Belfast's Donegall Road and James Galway brought the flute to popular attention.

In the field of sports Northern Ireland, given its relatively small population, has produced a plethora of top-rate athletes and experts such as George Best, Darren Clarke, Joey Dunlop, Alex Higgins, Denis Taylor, Eddie Irvine, Dave McAuley, Willie John McBride, Wayne McCullough, David Healy, Norman Whiteside, Martin O'Neill and the Olympic gold medallist Mary Peters.

The region included two of the most important ancient centres of learning and religious instruction, Bangor and Movilla (now Newtownards), from which missionaries spread Christianity throughout the British Isles and Europe.

History

See:

Historiography

Regan (2007) asks to what extent has the recent war in Northern Ireland influenced Irish historiography? Examining the nomenclature, periodization, and the use of democracy and state legitimization as interpretative tools in the historicization of the Irish Civil War (1922–3), the influence of a southern nationalist ideology is apparent. A dominating southern nationalist interest represented the revolutionary political elite's Realpolitik after 1920, though its pan-nationalist rhetoric obscured this. Ignoring southern nationalism as a cogent influence has led to the misrepresentation of nationalism as ethnically homogeneous in twentieth-century Ireland. Once this is identified, historiographical and methodological problems are illuminated, which may be demonstrated in historians' work on the revolutionary period (c. 1912–23). Following the northern crisis's emergence in the late 1960s, the Republic's Irish governments required a revised public history that could reconcile the state's violent and revolutionary origins with its counterinsurgency against militarist-republicanism. At the same time many historians adopted constitutional, later democratic, state formation narratives for the south at the expense of historical precision. This facilitated a broader state-centred and statist historiography, mirroring the Republic's desire to re-orientate its nationalism away from irredentism, toward the conscious accommodation of partition. Reconciliation of southern nationalist identities with its state represents a singular political achievement, as well as a concomitant historiographical problem.[1]