Mercer Beasley

Charles Fenton Mercer Beasley (July 17 or 18[1], 1882-1965), although generally forgotten today, was by far the best-known American tennis coach of the first half of the 20th century. Most articles about Beasley say that 17 of his pupils won 84 national titles between them, although apparently this was Beasley's own reckoning and remains to be confirmed.[2] Among his numerous star pupils were two of the best tennis players of all time, Ellsworth Vines and Frank Parker. Another famous pupil was Bitsy Grant, a top player of the 1930s, and his name is also associated with other great players such as Helen Jacobs, Gardnar Mulloy, Doris Hart, and Pancho Segura, although to what precise degree is no longer clear.[3] Carolin Babcock, now largely forgotten, was also a Beasley pupil who was a fine 1930s player. Beasley himself suffered from extremely poor eyesight; although he participated as a youth in some school sports, it was impossible for him to play tennis at more than a rudimentary level. In this he was probably unique: most other well-known tennis coaches such as the Australian Harry Hopman and Pancho Segura had generally been great or near-great tennis players in their own right.

Early life

Beasley came from a family of distinguished New Jersey jurists. His grandfather, an earlier Mercer Beasley (1815-1897), presided as Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court from 1864 to 1897. His father, Chauncey H. Beasley, was a District Court Judge. An uncle, Mercer Beasley Jr., who committed suicide at age 47, was a longtime county Prosecutor of the Plea. A second uncle, William S. Gummere, was yet another Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court, from 1901 to 1933. For many years there was a Mercer Beasley School of Law, which eventually merged into the New Jersey university system. Young Beasley attended one of America's leading prep schools, Lawrenceville School, also in New Jersey, then briefly and unsuccessfully went to Princeton University in 1902, from which he was soon expelled:

A local paper referred to Beasley's "passing out" and being "ousted" in the span of four months, and reported, "for some reason or other the faculty did not agree with his [Beasley's] solution to academic problems."[4]

Beasley then worked at a number of jobs for the next 17 years including being a court investigator for the New Jersey Public Railway Company[5] and a pressman’s devil.

Tennis background

Beasley first took up tennis at age 11 on his father's lawn, "dressed for the game in cricket flannels, blazer and Eton cap".[6]

"I always loved tennis," says Beasley, "but I never could play it.".... As a student at Lawrenceville School he couldn't make the tennis team but did play on his house football squad, weighing a fierce but fragile 120 pounds."[7]

At Lawrenceville, according to Time magazine,[8] in spite of his inadequacies he did play tennis with a near-contemporary, Karl Behr, who went on to become the No. 3 American player in 1907.

Eventually, after being expelled from Princeton, and holding a succession of jobs, he became the assistant manager of the Notlek Amusement Company in Manhattan, where, among other things, he was the maintenance man around their tennis courts.[9] The company apparently had a number of vacant lots, on which they provided tennis courts in the summer and ice skating rinks in the winter. Beasley knew about enough about tennis to begin giving informal lessons at the courts. Victor Elting, a scion of a socially prominent Chicago family of that name, was impressed by Beasley and invited him to become a teaching professional at the wealthy Indian Hill Club of Winnetka, Illinois.[10] Nearly 40, Beasley had found the career that would make him "the best known teacher in the history of U.S. tennis," as Time magazine called him in 1932.[11]

Coaching career at schools

Beasley was the coach at numerous schools and colleges, including Tulane, Lawrenceville, Princeton, and the University of Miami, while apparently also holding positions at various clubs. He spent five years at Tulane University in New Orleans, from 1929 through 1933, where his most successful pupil was Cliff Sutter, the NCAA singles champion in both 1930 and 1932, and who was ranked in the U.S. Top Ten for five consecutive years in the early 1930s. At the same time he was the coach at Tulane, he was also an instructor at the Detroit Tennis Club.[12]

In 1933 Beasley returned to his alma mater, Princeton, and, except for a year away in 1938,[13] coached its tennis team through 1942, compiling a dual-match mark of 71-12-1[14] and a total record of 89-20-1 with back-to-back Eastern Intercollegiate Tennis Association (EITA) championships in 1941 and 1942.[15]

Beasley's 1946 stint at the University of Miami, however, was brief and far less successful: an overall record of only 4-2-1. By contrast, his predecessor (and successor), the great amateur player Gardnar Mulloy, compiled an almost unbelievable record of 725-2.[16] For at least one of Mulloy's years (1943), he benefitted from the presence on the team of three-time NCAA singles champion Pancho Segura, one of the all-time greats of tennis. By the time Beasley took over the reins of the team, however, Segura had graduated.

Many years after his death in 1965 Beasley was inducted into the National Collegiate Tennis Hall of Fame at the University of Georgia in 2001.[17]

Ellsworth Vines

Beasley discovered the 14-year-old Ellsworth Vines working in a bakery in Pasadena and helped form him into one of the greatest players in the history of the game. The New York Times obituary of Vines has a slightly different age: Vines was a 15-year-old high-school student at Pasadena High when he was spotted by Beasley, then 44 and with only four years of coaching experience, and who had not yet become the most famous tennis court in America. Beasley himself said of the 20-year-old Vines in 1932:

"I found Ellsworth working in Kay's Bakery Shop in Pasadena.... He had a Western grip and a roundhouse swing, was about six feet tall and his feet wouldn't be friends with each other. But he had the heart and the willingness.... He was determined to hit hard.... while I fretted over errors."[18]

According to the New York Times obituary:

Beasley...flattened his serve and forehand into the rifle shots they became and used ingenuity in developing his fabled accuracy. A narrow strip of canvas with cutouts would be stretched across the top of the net, and Vines would spend hours drilling balls through the holes.[19]

The youthful Vines was one of the dominant players in the world throughout the 1930s and has been called by many competent observers such as Jack Kramer and Don Budge the greatest player of all time when his somewhat erratic game was on.

Frank Parker

Of the 16-year-old Frank Parker, who in 1932 had already beaten the No. 2 American, George Lott, four times, Beasley said:

"It was in 1927 that Frankie Parker came into my life. Little shaver, thin, puny, but quiet and attentive.... He had the best eye for a moving ball I've ever seen.... It took four years of the hardest work to get the boy's title.... Last year the wonder boy never lost a set.... He is to be the best of the pack."[20]

Under Beasley's tutelage, Parker became the first of only two players to ever win the national championships for boys (through 15), juniors (through 18), and men, the other being Joe Hunt a few years later. Beginning at the age of 17, in 1933, Parker was ranked among the Top 10 American players for 17 consecutive years, through 1949, a record for male players that stood until being surpassed by Jimmy Connors in 1988.

Frank Parker and Beasley's wife

Beasley and his wife essentially adopted the youthful Parker, taking him with them from teaching job to teaching job.[21] Under Beasley's tutelage Parker was the national boys champion, the national juniors champion, and then, at age 17, the eighth-ranked male player in the country. Six months younger than the great Don Budge, he consistently ranked higher than Budge until the latter turned 20.

According to Jack Kramer, another great near-contemporary of Parker's, and many other observers, the youthful Parker, an emotionless, robot-like tennis-stroking machine, had originally had "a wonderful slightly overspin forehand drive. Clean and hard."[22] Then, according to Kramer,

for some reason Beasley decided to change this stroke into a chop. It was obscene; it was like painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa.... Beasley got it into his head that Parker should hit with a forehand like Leo Durocher threw the ball from shortstop to first base. That was what Beasley patterned Parker's new forehand after.

Parker's revamped forehand was not a success; writing about the 22-year-old Parker in 1938, Time magazine said that while he had "learned Beasley accuracy and strategy, developed several trick strokes—notably "the shovel"—but never perfected a strong forehand."[23] In a 1935 controversy after the 19-year-old Parker had been defeated in an early round by Fred Perry in the United States championships, Parker declared that he was quitting to school to work on his forehand with Beasley in Bermuda. Beasley himself then announced that, "Frankie's got a swelled head. I tried to make him use the circle swingback but he wouldn't listen to me...."[24] For years after breaking from Beasley he attempted to reconstruct his original stroke but never entirely recovered it and, according to Kramer, never quite achieved the ultimate heights that he might have otherwise.

As a strange sidelight to Parker's longtime relationship with Beasley, the youthful player and Beasley's wife, Audrey, who was at least 20 years Parker's senior and had been his surrogate mother during all his teen years, fell in love, hiding the fact from Mercer for a number of years. In 1938, however, when Parker was 22, the Beasleys divorced and Audrey married the much younger Parker. The marriage, however, was apparently a happy one for 43 years until Audrey died in 1971.[25]

Coaching techniques

Years later, one of his pupils recalled some lessons given him by Beasley at a resort in Nassau:

"Mr. Beasley would put towels at various spots on the court and he had them numbered....He would stand at the net and yell out a number, and that meant for me to hit the ball to that spot. He would do it in rapid fire succession and it was a good coaching gimmick."[26]

Beasley's 1933 book, "How to Play Tennis", was a highly influential book that emphasized accuracy and consistent play. He was also the first coach to see the value of so-called cross-training, in which he had his pupils develop different aspects of their game by emulating the movements from other sports such as gymnastics, basketball, track, boxing, and ballroom dancing.

Of Beasley Methods: "I rarely change natural grips. . . . We find that if the pivot comes in, direction will follow if the racket follows in a line to where the ball is sent. . . . We try to have the footwork done ahead of time and then at the moment of hitting, perfect control, no falling over sideways, no off balance. . . . There is no lack of decision. The training calls for audible calling of where the ball is to be sent. We have used semaphores placed back of the player receiving the ball, the other fellow would follow the signals. . . . I do not allow more than 13 errors for any one set. . . . At Tulane we advocate and play basketball, we hit ten-nis balls with a golf stick from a cocoa mat on the tennis courts, we have the boxing instructor come down to the courts with boxing gloves and show the boys how to foot. We have the head football coach . . . we get the band out . . . we dance, keep moving and make every one of our varsity players work on one of our six practice boards. . . . There is a circle about one foot round they have to serve in. . . . My players must never grandstand a play, never make the kill when a soft accurate shot will suffice. Energy must be saved. No false steps, no excess movements. No jerks, no wild swinging and no brute strength. Just the cool calculating mind working the system, analytical, severe, fast, cruel and deadly. . . ."[27]

Commercial success

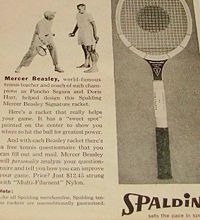

Beasley became a consultant to the Spalding Sporting Goods company in 1935, and for many years held tennis clinics for children in public parks across the country.[28] His book How to Play Tennis, first published in 1933, went through numerous printings and eventually he became so well known that Spalding released its own Mercer Beasley racket. For many years it was sold in stores next to those endorsed by Don Budge and Jack Kramer and it is said that both Pancho Gonzales and Ted Schroeder, the two finalists in a famous 1949 match at the U.S. Championship at Forest Hills, were playing with his racket. Finally, Beasley was constantly seeking technological improvements. It is said[29] that he was a pioneer in promoting synthetic strings, composite rackets, and ultralight footwear as well as being one of the first coaches to design and use the now-ubiquitous tennis ball machine.

References

- ↑ Different sources give different days for his birth

- ↑ "Mercer Beasley," July 29, 1957, in Sports Illustrated at [1]

- ↑ "Justice Deferred: The Case for Mercer Beasley", by Brook Zelcer, Tennis Week, Wednesday, September 7, 2008, at [2]

- ↑ "Justice Deferred: The Case for Mercer Beasley", by Brook Zelcer, Tennis Week, Wednesday, September 7, 2008, at [3]

- ↑ "Hall to honor two gentlemen of tennis", by Dan Magill in the Athens Banner-Herald, May 18, 2001, at [4]

- ↑ "Mercer Beasley," July 29, 1957, in Sports Illustrated at [5]

- ↑ "Mercer Beasley," July 29, 1957, in Sports Illustrated at [6]

- ↑ "Sport: At Forest Hills", Time magazine, Monday, September 12, 1932, at [7]

- ↑ "Those who can't, teach, Great tennis coach neglected by history" by Brittany Urick, article in the Daily Princetonian, February 22, 2007 at [8]

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Sport: At Forest Hills", Time magazine, Monday, September 12, 1932, at [9]

- ↑ "Sport: At Forest Hills", Time magazine, Monday, September 12, 1932, at [10]

- ↑ "Those who can't, teach, Great tennis coach neglected by history" by Brittany Urick, article in the Daily Princetonian, February 22, 2007 at [11]

- ↑ "Hall to honor two gentlemen of tennis", by Dan Magill in the Athens Banner-Herald, May 18, 2001, at [12]

- ↑ "Those who can't, teach, Great tennis coach neglected by history" by Brittany Urick, article in the Daily Princetonian, February 22, 2007 at [13]

- ↑ "Quick Fact" in the University of Miami Tennis Media Guide at [14]

- ↑ "Hall to honor two gentlemen of tennis", by Dan Magill in the Athens Banner-Herald, May 18, 2001, at [15]

- ↑ "Sport: At Forest Hills", Time magazine, Monday, September 12, 1932, at [16]

- ↑ New York Times, March 20, 1994, obituary of Vines, at [17]

- ↑ "Sport: At Forest Hills", Time magazine, Monday, September 12, 1932, at [18]

- ↑ It is uncertain whether the youth was ever legally adopted by the Beasleys; some sources of the 1930s such as the Time magazine of September 16, 1935, [19] say that he was; at other times he is referred to only as their "foster" child.

- ↑ The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis, Jack Kramer with Frank Deford, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1979, (ISBN 0-399-12336-9), page 48

- ↑ "Sport:Love Set", Time magazine, March 29, 1938, at[20]<

- ↑ "Sport: Rain at Forest Hills", Time magazine, September 16, 1935 at, [21]

- ↑ The New York Times obituary of Parker, July 28, 1997, at [22]

- ↑ "Hall to honor two gentlemen of tennis", by Dan Magill in the Athens Banner-Herald, May 18, 2001, at [23]

- ↑ "Mercer Beasley," July 29, 1957, in Sports Illustrated at [24]

- ↑ "Sport: At Forest Hills", Time magazine, Monday, September 12, 1932, at [25]

- ↑ "Those who can't, teach, Great tennis coach neglected by history" by Brittany Urick, article in the Daily Princetonian, February 22, 2007 at [26]