Christmas

Christmas has two main meanings: one, Christmas Day, an annual national holiday held on December 25 in many countries, and two, Christmastide, also known as The Twelve Days of Christmas, a holy season that marks the birth of Jesus, the central figure of Christianity. Christmas traditions include the display of Nativity scenes, holly and Christmas trees, the exchange of gifts and cards, and the arrival of Father Christmas or Santa Claus, also called Saint Nicholas. In addition, religious observances include special church services, the singing of particular hymns and carols and Nativity plays. Christmas has inspired a wide range of music, literature and performance art.

In Western countries, Christmas has become the most economically significant holiday of the year. In the United States, the holiday of Thanksgiving marks the beginning of the Christmas season, although shopkeepers may begin Christmas marketing several weeks before this, and continue promotions through the "after-Christmas sales" of January.

The modern celebration of Christmas blends modern religious and ancient pagan elements. The origins of Christmas can be traced in part to pre-Christian winter festivals. Many cultures have their most important holiday in winter because there is less agricultural work to do at this time. Examples of winter festivals that may have influenced Christmas include the pagan festivals of Yule and Saturnalia.

In most observances, the Christmas season begins on December 25 and ends on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6th, although this date is merely traditional, as the actual date of the birth of Jesus is unknown.[1] Most Orthodox Churches celebrate Christmas on January 7, the date on the Gregorian calendar which corresponds to December 25 on the Julian Calendar.

Etymology

The word "Christmas" is a contraction of "Christ's Mass." It is derived from the Middle English Christemasse and Old English Cristes mæsse.[2] Dutch has a similar word, Kerstmis often shortened to Kerst. The words for the holiday in Spanish (navidad), Portuguese (natal), Polish (Boże Narodzenie), French (noël), and Italian (natale), refer explicitly to the Nativity. In contrast, the German name Weihnachten means simply "hallowed night." The Anglo-Saxons referred to Christmas as geol,[2] the name of a pre-Christian winter festival from which the current English word "Yule" is derived.

Christmas is sometimes shortened to Xmas, an abbreviation that has a long history.[3] In early Greek versions of the New Testament, the letter Χ (chi), is the first letter of Christ (Χριστός). Since the mid-sixteenth century Χ, or the similar Roman letter X, has been used as an abbreviation for Christ.[4]

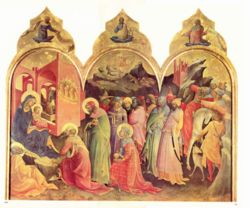

The Nativity

The Gospel of Matthew[5] and the Gospel of Luke[6] each contains a distinct version of the Nativity story. According to these accounts, Jesus was born to Mary, assisted by her husband Joseph, in the town of Bethlehem (literally the "House of bread", also called "David's City", a place of historical importance to the ancient Jews). Because Luke's version mentions that the infant Jesus was laid in a "manger", a hay-filled animal feeder, the birth is presumed to have taken place in a stable of sorts, with the Holy Family surrounded by farm animals. Shepherds from the fields surrounding Bethlehem were told of the birth by an angel, and were the first to see the child.[7] Christians believe that the birth of Jesus fulfilled prophecies made hundreds of years before his birth. Later, three "wise men from the East" (known in Christian tradition as The Magi, the Three Wise Men or The Three Kings) visited as well, [8] bringing expensive gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. These wise men are traditionally referred to as Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar, although their names and number are not referred to in the Biblical narrative. They are said to have followed a star, known as the Star of Bethlehem to Jerusalem, and found Jesus, whom they believed to be "the King of the Jews". Matthew's narrative includes a political aside involving King Herod of Judea being troubled and jealous at the thought of the birth of another king.

Remembering or re-creating the Nativity is a central way that Christians celebrate Christmas. The Orthodox Church practices the Nativity Fast in anticipation of the birth of Jesus, while much of the Western Church observes Advent. In many Christian churches, congregants perform plays re-telling the events of the Nativity; in some churches it a tradition that these Nativity plays are performed by children. Some Christians also display a small re-creation of the Nativity, known as a Nativity Scene, in their homes, using figurines to portray the key characters of the event. Live Nativity Scenes are also performed, using actors and live animals to portray the event with more realism.[9]

In the U.S., Christmas decorations at public buildings once commonly included Nativity scenes. This practice led to many lawsuits which argued that the practice amounted to a government endorsement of a religion. In 1984, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a city-owned Christmas display, even one with a Nativity scene, does not violate the First Amendment.[10]

History

Origin of the festival

The New Testament does not give a date for the birth for Jesus. The Romans considered December 25 to be the date of the winter solstice, which they called bruma. Jesus was associated with solar days because he was identified with the "sun of righteousness."[11] Sextus Julius Africanus popularized the idea that Jesus was born on December 25 in Chronographiai (AD 221), a now lost reference book for Christians.[12] This date is nine months after the traditional date of the incarnation (March 25), now celebrated as the Feast of the Annunciation.[13] On the Roman calendar, March 25 was the date of the vernal equinox and early Christians believed it was also the date that Jesus was crucified.[13] The Christian idea that Jesus was conceived on the same date that he died is consistent with a Jewish belief that a prophet lived an integral number of years.[13]

The identification of the birthdate of Jesus did not at first inspire feasting or celebration. In 245, the theologian Origen denounced the idea of celebrating Jesus' birthday "as if he were a king pharaoh." He contended that only sinners, not saints, celebrated their birthdays.

The earliest reference to the celebration of Christmas is in the Calendar of Filocalus, an illuminated manuscript compiled in Rome in 354.[2][14] In the east, meanwhile, Christians celebrated the birth of Jesus as part of Epiphany (January 6), although this festival focused on the baptism of Jesus.[15]

Christmas was promoted in the east as part of the revival of Catholicism following the death of the pro-Arian Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. The feast was introduced to Constantinople in 379, to Antioch in about 380, and to Alexandria in about 430. Christmas was especially controversial in fourth Constantinople, being the "fortress of Arianism," as Edward Gibbon described it. The feast disappeared after Gregory of Nazianzus resigned as bishop in 381, although it was reintroduced by John Chrysostom in about 400.[2] Over the course of time it was adopted by all the Eastern churches except the Armenian.

Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages, Christmas Day was overshadowed by Epiphany, which in the west focused on the visit of the magi.[16] But the Medieval calendar was dominated by Christmas-related holidays. The forty days before Christmas became the "forty days of St. Martin," now known as Advent.[16] In Italy, former Saturnalian traditions were attached to Advent.[16]

The gradual increase in the prominence of Christmas Day may reflect the influence of Yule, a pre-Christian northern European festival which was rescheduled to correspond with Christmas. Charlemagne was crowned on Christmas Day in 800 and King William I of England was crowned on Christmas Day 1066.

Around the twelfth century, the hedonistic traditions of Saturnalia transferred again to the "twelve days of Christmas" (December 25 - January 5).[16] The evening of January 5 was called "twelfth night," a festival later celebrated by William Shakespeare in a play of that name.

By the High Middle Ages, the holiday had become so prominent that chroniclers routinely noted where various magnates celebrated Christmas.[16] King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which twenty-eight oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten.[16] The "Yule boar" was a common feature of medieval Christmas feasts.[16] Caroling was also popular.[16] This was originally a group of dancers who sang.[16] The group was composed of a lead singer and a ring of dancers that provided the chorus.[16] Various writers of the time condemned caroling as lewd, so perhaps the unruly traditions of Saturnalia and Yule continued in this form.[16] "Misrule" — drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling — was also an important aspect of the festival.[16] Indeed, in some locations, a "Lord of Misrule" was appointed - a commoner or serf put in charge for the feast. This is possibly the origin of the paper crown present in modern day Christmas crackers. In England, gifts were exchanged on New Year's Day and there was special Christmas ale.[16]

The Reformation and the 1800s

During the Reformation, Protestants condemned Christmas celebration as "trappings of popery" and the "rags of the Beast".[17] The Catholic Church responded by promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form.[17] Following the Parliamentary victory over King Charles I during the English Civil War, England's Puritan rulers banned Christmas (1647).[17] Pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities and for several weeks Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans.[17] The Restoration of 1660 ended the ban, but most Anglican clergymen still disapproved of Christmas celebration.[17]

In colonial America, the Puritans of New England disapproved of Christmas and outlawed its celebration in Boston (1659-81). At the same time, Christian residents of Virginia and New York observed the holiday freely. Christmas fell out of favor in the United States after the American Revolution, when it was considered an English custom.

By the 1820s, sectarian tension had eased and British writers began to worry that Christmas was dying out. They imagined Tudor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration, and efforts were made to revive the holiday. Charles Dickens' book A Christmas Carol (1843) played a major role in reinventing Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion, as opposed to communal celebration and hedonistic excess.[18]

Interest in Christmas in America was revived in the 1820s by several short stories by Washington Irving which appear in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon and "Old Christmas", and by Clement Clarke Moore's 1822 poem A Visit From St. Nicholas (also known as Twas the Night Before Christmas). Irving's stories depicted harmonious warm-hearted holiday traditions he claimed to have observed in England. Although some argue that Irving invented the traditions he describes, they were widely imitated by his American readers. The numerous German immigrants and the homecomings following the American Civil War also helped promote the holiday. Christmas was declared a U.S. Federal holiday in 1870.

The 20th century and after

In 1914, the first year of World War I, there was an unofficial truce between German and British armies in France. Soldiers on both sides spontaneously began to sing carols and stopped fighting. The truce began on Christmas Day and continued for some time afterwards.[19] Many stories about the truce include a soccer game between the trench lines.

Since a 1962 U.S Supreme Court regarding school prayer, Christmas has been the subject of controversy in the United States. Some considered the U.S. government's recognition of Christmas as a federal holiday to be a violation of the separation of church and state. This was brought to trial several times, recently including in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984)[10] and Ganulin v. United States (1999).[20] According to Ganulin, "the establishment of Christmas Day as a legal public holiday does not violate the Establishment Clause because it has a valid secular purpose." This decision was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2000. Many devout Christians objected to what they saw as the vulgarization and cooption of one of their sacred observances by secular commercial society and calls to return to "the true meaning of Christmas" were common.

Controversy over Christmas erupted again in 2005, when retailers, including Walmart, promoted the use of the phrase "happy holidays" as opposed to the traditional "merry Christmas." American political commentators such as Bill O'Reilly protested this as part of what they claimed was general trend to secularize society.[21]

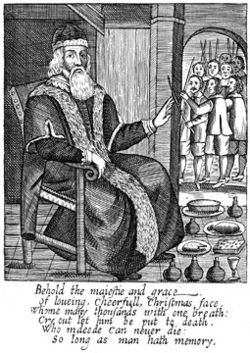

Santa Claus

The holiday is characterized by the exchange of gifts among friends and family members, some of which are attributed to "Santa Claus," also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas or St. Nikolaus, or Kris Kringle. The name Santa Claus is derived from the Dutch Sinterklaas, a contraction of Sint Nicolaas (Saint Nicholas). Sinterklaas gave gifts to Dutch children on December 5 and was therefore a part of New York's heritage as a former Dutch colony. He became associated with Christmas as a result of Irving's History of New York, (1809). Moore's poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas" (1823) is responsible for establishing Santa Claus in the mind of the American public.

The image of Santa Claus was created by the German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840-1902), who drew a new image annually, beginning in 1863. By the 1880s, Nast's Santa had evolved into the form we now recognize. The image was standardized by advertisers in the 1920s.[22]

Father Christmas, who predates Santa Claus, was first recorded in the 15th century, but he was originally associated with holiday merrymaking and drunkenness.[23] In Victorian Britain, his image was remade to match that of Santa. France's Père Noël has a similar history. In Italy, "Babbo Natale" acts as Santa Claus while "La Befana" brings gifts on the eve of the Epiphany.

Christmas trees and other decorations

The Christmas tree represents an adaptation of Germanic traditions regarding the use of evergreen boughs.[24] The English language phrase "Christmas tree" was first recorded in 1835[23] and represents an importation from German.

The modern Christmas tree tradition is believed to have begun in Germany in the 18th century[25] From Germany the custom was introduced to England, first via Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, and then more successfully by Prince Albert during the reign of Queen Victoria. Around the same time, German immigrants introduced the custom into the United States.[26] Christmas trees may be decorated with lights and ornaments.

Since the 19th century, the poinsettia has been associated with Christmas. Along with a Christmas tree, the interior of a home may be decorated with these plants, along with garlands and evergreen foliage.

Economics of Christmas

In most areas, Christmas Day is the least active day of the year for business and commerce; almost all retail, commercial and institutional businesses are closed, and almost all industries cease activity (more than any other day of the year). In England and Wales, the Christmas Day (Trading) Act 2004 prevents all large shops from trading on Christmas Day. Scotland is currently planning similar legislation. Film studios release many high-budget movies in the holiday season, including Christmas films, fantasy movies or high-tone dramas with high production values.

Commercialization

Once the 1823 poem "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" had popularized the tradition of exchanging gifts, Christmas shopping gradually began to assume economic importance.[27] In her 1850 book "The First Christmas in New England", Harriet Beecher Stowe has a character complain that the true meaning of Christmas was being lost in a shopping spree.[28]

The economic importance of Christmas was highlighted when President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed moving up the Thanksgiving holiday date to extend the Christmas shopping season and boost the economy.[29] In their 1931 Christmas sermons, American clergymen responded by denouncing efforts to commercialize the holiday.[30]

References

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Church, Oxford University Press, London (1977), p. 280.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Christmas", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913.

- ↑ Bratcher, Dennis. "The Christmas Season" The Voice, CRI/Voice, Institute, 2006.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ Matthew 2:18-25 Matthew 1:18-2:12

- ↑ Luke 1:26-38; 2:1-7 Luke 1:26-56

- ↑ Luke 2:8-20 Luke 2:1-6

- ↑ Matthew 2: 1-12

- ↑ Krug, Nora. "Little Towns of Bethlehem", The New York Times, November 25, 2005.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Lynch vs. Donnelly (1984)

- ↑ Malachi 4:2.

- ↑ "Christmas, Encyclopædia Britannica Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 "The Feast of the Annunciation", Catholic Encyclopedia, 1998.

- ↑ This document was prepared privately for a Roman aristocrat and is named after an artist who illuminated part of it. The reference to Christmas states, VIII kal. ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeæ. It is in a section based on an earlier manuscript produced in 336.

- ↑ Pokhilko, Hieromonk Nicholas, "The Formation of Epiphany according to Different Traditions

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 Murray, Alexander, "Medieval Christmas", History Today, December 1986, 36 (12), pp. 31 - 39.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Durston, Chris, "Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642-60", History Today, December 1985, 35 (12) pp. 7 - 14.

- ↑ Rowell, Geoffrey, "Dickens and the Construction of Christmas", History Today, December 1993, 43 (12), pp. 17 - 24.

- ↑ Baker, Chris, The Christmas Truce of 1914, 1996

- ↑ Ganulin v. United States (1999)

- ↑ Cohen, Adam. "This season's war cry: Commercialize Christmas, or else." The New York Times, December 5, 2005.

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara and David P., "The Claus That Refreshes", Snopes.com, 2006.

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Harper, Douglas, Christ, Online Etymology Dictionary, 2001.

- ↑ Robinson, B.A. "All about the Christmas tree: Pagan origins, Christian adaptation, & secular status" ReligiousTolerance.Org, December 13, 2003.

- ↑ van Renterghem, Tony. When Santa was a shaman. St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-56718-765-X

- ↑ Morris, Desmond. Christmas Watching. London: Mackays of Chatham, 1992. ISBN 0-224-03598-3

- ↑ usinfo.state.gov “Americans Celebrate Christmas in Diverse Ways” November 26, 2006

- ↑ First Presbyterian Church of Watertown “Oh . . . and one more thing” December 11, 2005

- ↑ usinfo.state.gov “Americans Celebrate Christmas in Diverse Ways” November 26, 2006

- ↑ New York Times “This Season's War Cry: Commercialize Christmas, or Else ”December 4, 2005