Eugene Debs

Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926) was an American Socialist leader and candidate for president.

Debs was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, Nov. 5, 1855; he lived there all his life. He was one of ten children of French immigrants from Alsace. He went to work as a locomotive fireman in 1870; in 1875 he helped form a lodge of the brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, and in 1880 he was made national secretary and treasurer of the brotherhood, as well as editor of its magazine. From 1879 to 1883 Debs also served as city clerk of Terre Haute, and in 1884 he was elected for a term in the Indiana state legislature as a Democrat.

Pullman Strike, 1894

A persistent critic of the organization of labor by crafts (such as locomotive firemen), Debs in 1893 left his old union and created the American Railway Union to include all workers, even those belonging to other unions. Established unions denounced it as "dual unionism," but with the severe Depression of 1893 underway, workers were angry and wanted an aggressive union. Its main success came in April 1894 when it won a strike against the Great Northern Railroad. When the Pullman factory strike erupted in Chicago in late spring 1894, the ARU organized the workers, but Pullman refused to negotiate with them. The ARU then called for a boycott of railroads using Pullman cars (which most did), even though the ARU had no grievances against the railroads. The result was a nationwide strike that was especially severe west of Detroit, as violence broke out in many cities. President Grover Cleveland intervened and obtained a court order to end the strike (because it was disrupting the mails). Debs and the ARU refused to obey. Debs was held in contempt of court for violating the federal injunction and served six months in jail. The strike and the ARU collapsed.

Socialist Party leader

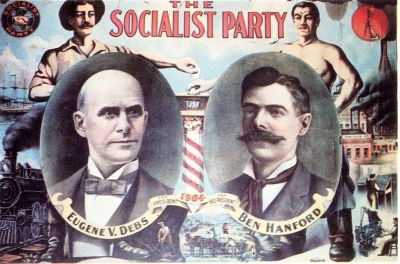

Long interested in socialism in the abstract, Debs read widely on the subject while in prison, and in 1897 he transformed the remnants of the ARU into the Social Democratic Party of America, later called the Socialist Party of America. He never again engaged in union work. He served as associate editor of the Socialist weekly, the Appeal to Reason, (based in the coal mining town of of Girard, Kansas) and for years was a highly successful lecturer on behalf of socialism. In 1905, he helped found the radical Industrial Workers of the World, but soon quit. The Socialist Party was splintered and Debs was one of the few leaders with an appeal to the intellectuals, the "gas-and-water" conservatives (who wanted municipal ownership), the ethnic Germans and Jews, the well-organized coal miners, the ex-Populists from Kansas and Oklahoma, and the IWW-like radicals who wanted to destroy capitalism. Debs ran for president of the United States on the Socialist ticket five times, 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920. Debs in 1908, toured both west and east in a special campaign train, the "Red Special." Nationwide, Socialists increased their 1908 vote totals by only 20,000 over 1904. Debs' speeches aimed to provide but an education in socialist views; he spoke to some 300,000 westerners and saw his vote in Colorado double, In 1912 he polled over 900,000 votes, nearly 6 percent of the total cast.

Corbin (1978) argues that Debs' favorable image as a friend of the workingman is undeserved, for his attitudes and actions concerning local affiliates and rank-and-file members actually hurt the development of the Socialist Party of America. This was especially critical in the West Virginia coal strike of 1912-14. Not only did the national office of the SPA ignore the strike for a year, but when Debs finally intervened with an investigating committee, he urged coal miners to accept a questionable compromise. He also exonerated Governor Hatfield of charges of having abused his power, even though a US congressional committee reached the opposite conclusion. By ignoring the wishes of the miners and by betraying local Socialist affiliates, Debs did considerable damage to Socialist solidarity in West Virginia's coal fields, according to Corbin.

Jailed for antiwar speech in 1918

When the U.S. entered World War I Debs supported the manifesto of the St. Louis convention of the party (April 1917), denouncing the war and counseling party members to oppose it by all means in their power. At the Socialist state convention in Canton, Ohio, June 16, 1918, he delivered a speech in which he bitterly assailed the Wilson administration for its prosecution of Socialists charged with sedition. He was indicted by a federal grand jury for a violation of the Espionage Act, and on Sept. 14, after a four-days trial, was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment on each of two accounts. The U.S. Supreme Court on Mar. 10, 1919, upheld the verdict, and Debs went to federal prison. In 1920 his vote for president again exceeded 900,000, but was only 3% of the total as women did not respond well to his appeals. although he was in prison in Atlanta. At Christmas 1921 he was released by President Warren Harding. Debs then campaigned against prison conditions. He died in Elmhurst, Illinois., Oct. 20, 1926.

Religious issues

Religion posed a difficult problem for the Socialist movement in America. In Europe Socialists led the fight against established religion. In America, most of the industrial workers were Catholics, and the Catholic Church was controlled by Irish Americans who were closely allied with the Irish politicians who dominated the Democratic party in most cities. The Catholic Church was therefore the foremost enemy of socialism in America. Debs, however, was admired by the Protestant Christian Socialists and many ministers of the Social Gospel outlook. Personally Debs was a deist with little interest in theology or piety. He attacked organized churches--that is the Catholic Church--but used religious symbolism that appealed to his Protestant admirers. Debs condemned the use of religion as an instrument of class oppression, though he admired Jesus as a model agitator and identified with his sense of martyrdom.[1]

Legacy and ideas

Debs is best known for tireless campaigning and passionate oratory that made audiences feel guilty for not being more radical; he did not originate any new ideas or policies. Debs believed capitalism, with all its works, was evil, and Socialism, with all its promises, a true panacea.

Bibliography

- Almont, Lindsay. The Pullman Strike

- Burwood, Stephen. "Debsian Socialism Through a Transnational Lens." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 2003 2(3): 253-282. Issn: 1537-7814 Fulltext: in History Cooperative. Shows Debsian rhetoric was similar to rhetoric of European socialists.

- Chace, James. 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs-The Election That Changed the Country (2004), popular history

- Corbin, David A. "Betrayal in the West Virginia Coal Fields: Eugene V. Debs and the Socialist Party of America, 1912-1914." Journal of American History 1978 64(4): 987-1009. Issn: 0021-8723 Fulltext in Jstor

- Dorn, Jacob H. "'In Spiritual Communion': Eugene V. Debs and the Socialist Christians." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 2003 2(3): 303-325. Issn: 1537-7814 full text in History Cooperative

- Ginger, Roy. The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs (1949)

- Kipnis, Ira. The American Socialist Movement 1897-1912 (1952) online edition

- Lee, Ronald and Andrews, James R. "A Story of Rhetorical-ideological Transformation: Eugene V. Debs as Liberal Hero." Quarterly Journal of Speech 1991 77(1): 20-37. Issn: 0033-5630

- Morgan, H. Wayne. "The Utopia of Eugene V. Debs." American Quarterly 1959 11(2): 120-135. Fulltext in Jstor

- Morgan, H. Wayne. Eugene V. Debs (1962) by leading scholar; online edition

- Morgan, H. Wayne. Eugene v. Debs: Socialist for President (1973) online edition

- Quint; Howard H. The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement (1964) online edition

- Papke, David Ray. The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America. U. Press of Kansas, 1999. 118 pp.

- Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (2007), the main scholarly study

Primary sources

- Eugene Victor Debs, Debs: His Life, Writings and Speeches (1908), online edition

- Debs, Eugene V. Letters of Eugene V. Debs. Vol. 1: 1874-1912. Vol. 2: 1913-1919. Vol. 3: 1919-1926. J. Robert Constantine, ed. U. of Illinois Press, 1990. 1793 pp.

- Debs, Eugene. Gentle Rebel: Letters of Eugene V. Debs. Edited by J. Robert Constantine. 312 pages. (1995). selected version

- ↑ See Dorn (2003)