Hippocrates

- Note: Text in font-color unbolded blue links to articles in Citizendium; text in font-color Maroon links to articles not yet started (authors/editors encouraged to initiate such articles)

Of all the men in ancient Greece who shared the name, Hippocrates — a common Greek name like ‘Edward’ or ‘Lawrence’ in English — many with that name having distinguished themselves in Greek history in one way or other — only one named Hippocrates, Hippocrates of Cos (ca. 460 – 370 BCE), a physician-surgeon, earned such a high degree of respect and honor that his ideas flourished during Western history to the present day. He began and inspired a revolution in medicine that so changed the course of Western civilization that the health and welfare of all humanity has benefited.

Hippocrates of Cos revolutionized the practice of medicine by transforming it from its mythical, superstitious, magical and supernatural roots to roots based on observation and reason — the roots of scientific objectivity — roots that have nourished an ever-growing evolutionary tree of Western scientific medicine still flourishing. For that reason History has bestowed on Hippocrates of Cos the honorific cognomen, “The Father of Medicine”, medicine’s progenitor. We might call him more accurately "The Progenitor of Western Rational Medicine".

Because historians know only a little about the life of Hippocrates, and because of the great influence the works associated with his name have had on medicine for millennia, his fame as a physician has led to a plethora of writings about him that have the character of legend:

We still know very little about Hippocrates. And yet, like the physicians of Imperial Rome, the doctors of our days want to know all about the life of the "Father of Medicine." Where there are no historical sources available, imagination will step in, and the poet will replace the historian.[1]

The details — even basic facts — of Hippocrates' life remains contentious among modern classics scholars, to say the least. An unfortunate dearth of contemporary 5th and 4th century BCE historical information makes many questions about about the historical Hippocrates particularly knotty, and vexes the question of the relationship between the writings that have come down in Hippocrates' name, the Hippocratic corpus, and those among the corpus that Hippocrates himself, rather than his followers, may have written.

The legends about Hippocrates, whether completely imagined or evolved elaborations of reality, by their hero-generating nature, attest to the esteem bestowed on Hippocrates for nearly two and one-half millennia.[2]

Sources for the life of Hippocrates

Though Hippocrates looms large in the imagination and in historical tradition, unambiguous historical evidence for a satisfactorily full account of his life remains elusive. The evidence closest in time to Hippocrates' life comes to us from the extant writings of the philosopher Plato (429-347 BCE), a contemporary of Hippocrates. Plato has Socrates mentioning Hippocrates in the Protagoras and Phaedrus. These passages help us to locate Hippocrates in the context of Greek culture in the fifth century BCE. The latter reference (which has inspired a large body of scholarship) comments on Hippocrates' methodology. Together, the passages in Plato's works give us reliable evidence of the existence of Hippocrates as a physician, as a citizen of Cos, of the Asclepiad family, who had achieved fame beyond his homeland during his lifetime.[3] [4]

A passage in the Politics of Aristotle, a near contemporary of Hippocrates, also attests to Hippocrates' historical existence in a way that suggests his fame as a scientist physician.

Hippocrates' life and work are discussed in the writings of Aulus Cornelius Celsus (d. ca. 50 CE). An anonymous, mystifying papyrus tries to differentiate the real teachings of Hippocrates from those merely attributed to him.

Furthermore, it was recognized in antiquity that the Hippocratean corpus, the collection of writings attributed to Hippocrates, could not be the writings of one man. Later commentators, including the influential Galen, attempted to separate the genuine Hippocratean teachings from the spurious and included biographical detail when they did so.

One Life of Hippocrates, a short work attributed to Soranus of Ephesus (a second century CE physician), provides many details concerning Hippocrates' life. Jacques Jouanna refers to it as "the canonical source", as it appears introductory to the earliest compiled editions of the Hippocratic corpus.[5] Jouanna asserts that it "draws upon more ancient sources, the most outstanding of which is the director of the library of Alexandria during the Hellenistic era, Eratosthenes ofCyrene.

Given the lack of unambiguous contemporary evidence, a large number of modern scholars have concluded that the real, historical Hippocrates is unknowable. In recent years, the research of Jacques Jouanna has re-opened the debate on the life of Hippocrates, and on many points of Hippocratean scholarship.[5]

Hippocrates’ life on the island of Cos

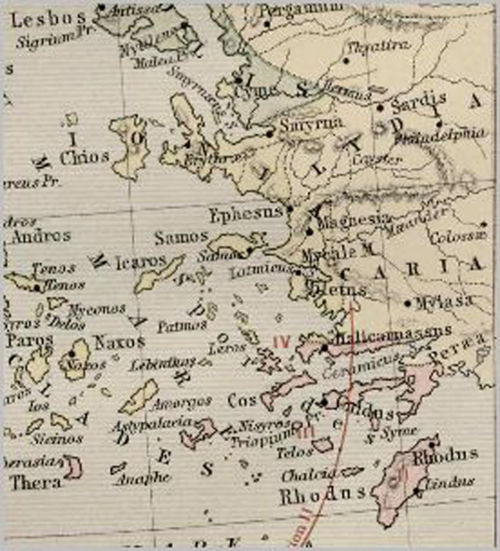

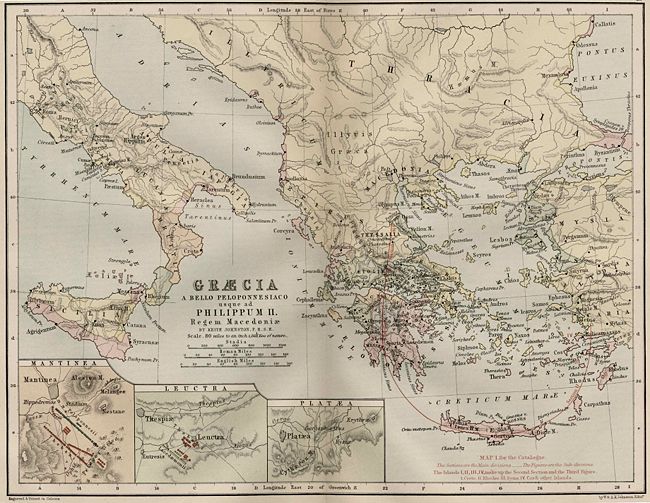

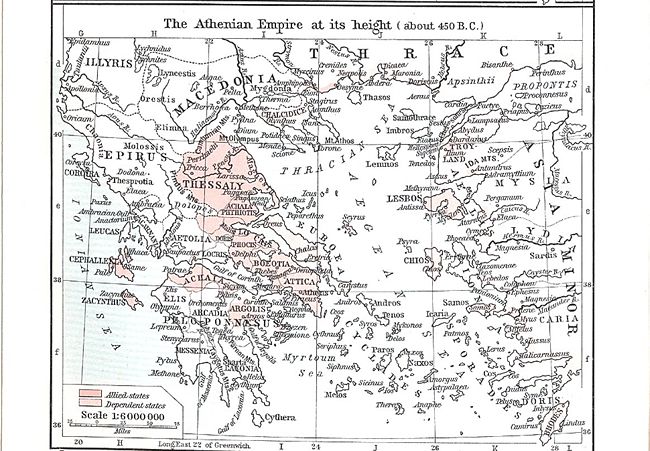

Hippocrates entered the world into an aristocratic family on the Ionian island of Cos (or Kos), located in the Aegean Sea off the southwest coast of then called Ionia (Asia Minor, present day Turkey).[6]

Hippocrates' father, Heraclides, and his father's father, also called Hippocrates, practiced medicine employing ancient ideas of supernatural causation and treatment of disease according to the tradition linked to Asclepius, considered a deity.[7] In fact, Heraclides traced his ancestry through the male line back to Asclepius in the era of the Trojan war, when Asclepius, a physician, had not yet received divine status. Heraclides descended through the male from Asclepius’s son, Podalirius, who fought in the Trojan war, moved to Asia Minor, and whose descendants eventually settled on Cos. The tradition of Asclepian medicine passed from son to son down the generations, eventually reaching Heraclides. The family from Podalirius onward called themselves Asclepiads, their family name.

At the time of Hippocrates’ birth, Cos paid tribute to Athens as a member of the Athenian federation created to defend against Persian aggression.

Hippocrates, though known also as 'Hippocrates of Cos, the Asclepiad', and though reared in the family tradition of Asclepian medicine, nevertheless rejected the supernatural ethos, substituting a naturalistic ethos, thereby sparking a revolution of principles and practice in medicine that present day non-supernatural Western scientific medicine acknowledges as its parentage and heritage.[8] Scholars have found no evidence of Hippocrates ever practicing as a physician priest of Asclepius.

Hippocrates’ education within the family probably included, in addition to medicine, philosophy and rhetoric and other subjects that gave him knowledge of the world of reality. He remained on Cos well into maturity, married and had two sons and a daughter. His new practice of medicine according to the tenets of observation and reason gained him fame in and beyond Cos. One plausible story has him rejecting an invitation to court of the current king of Persia. [9]

The emergence of Hippocratic medicine

|

The Greeks invented rational medicine. |

|

--James Longrigg[8] |

Hippocratic medicine reflected emerging philosophy of the natural causes of things and events in the world that began with the Ionian philosopher, Thales of Miletus (c. 625-546), whose speculation about the natural world is an important turning point in Western scientific thought. Classicist and historian of medicine, James Longrigg puts it thusly:

Our earliest evidence of Greek medicine reveals, then, that, as in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, the causation of disease and the operation of the remedies applied to the sick were so linked with superstitious beliefs in magic and supernatural causation that a rational understanding of disease, its effect upon the body, or of the operation of remedies applied to it was impossible. The sixty-odd works of the Hippocratic Corpus, however, provide a striking contrast and are virtually free from magic and supernatural intervention.[citation] Here, in this collection, for the first time in the history of medicine complete treatises have survived which display an entirely rational outlook towards disease, whose causes and symptoms are now accounted for in purely natural terms. The importance of this revolutionary innovation for the subsequent development of medicine can hardly be overstressed. This emancipation of (some) medicine from magic and superstition, was the outcome of precisely the same attitude of mind which the Milesian natural philosophers were the first to apply to the world about them. For it was their attempts to explain the world in terms of its visible constituents without recourse to supernatural intervention which ultimately paved the way for the transition to rational explanation in medicine, too.Cite error: Closing

</ref>missing for<ref>tag

The Hippocratic treatise, On Ancient Medicine, asserts that the practice of medicine does not derive from a priori first principles, as does the practice of some branches of philosophy, but from the findings in individual cases. Medicine does not qualify as philosophy, but as an observational science challenged by specific diseases arising from specific natural causes, the challenges met only by detailed observation leading to cumulative knowledge undergirded by rational reasoning.

Whoever having undertaken to speak or write on Medicine, have first laid down for themselves some hypothesis to their argument, such as hot, or cold, or moist, or dry, or whatever else they choose (thus reducing their subject within a narrow compass, and supposing only one or two original causes of diseases or of death among mankind), are all clearly mistaken in much that they say…. Wherefore I have not thought that it stood in need of an empty hypothesis, like those subjects which are occult and dubious, in attempting to handle which it is necessary to use some hypothesis; ; as, for example, with regard to things above us and things below the earth; if any one should treat of these and undertake to declare how they are constituted, the reader or hearer could not find out, whether what is delivered be true or false; for there is nothing which can be referred to in order to discover the truth.[10]

Hippocrates’ life overlapped that of the great Greek natural philosophers Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), Socrates (469–399 BCE), Plato (429-347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Thus he lived during the Golden Age of Greece (c. 500 – 300 BCE). Disease, so central in human lives, not surprisingly would come under scientific scrutiny in the environment of such thinkers. Historians know that Hippocrates observed keenly ("infinite in faculty"), reasoned rationally ("noble in reason"), and taught and practiced a holistic ideal of medicine ("what a piece of work is Man")[11] [12] that regarded health and disease as manifestations of body and mind as a whole. An excerpt from one of the Hippocratic Treatises, Places in Man, nicely illustrates the Hippocratic holistic view.[13]

In my view, there is no beginning in the body; but everything is alike beginning and end. For when a circle has been drawn, its beginning is not to be found. And the beginning of ailments comes from the entire body alike. . . . Each part of the body at once transmits illness one to the other, whenever it arises in one place or another; belly to head, head to flesh and to belly, and all other parts thus analogously, just as belly to head and head to flesh and to belly. For when the belly fails to make proper evacuation, and food goes into it, it floods the body with moisture from the ingested foodstuffs. . . . .This moisture, blocked from the belly, travels en masse to the head. When it reaches the head, not being contained by the vessels in the head, it flows at random, either around the head or into the brain through the fine bone. Some penetrates the bone and some the region of the brain through the fine bone. And if it returns to the belly, it causes illness in the belly; and if it happens to go anywhere else, it causes illness elsewhere; and in other cases similarly, just as in this case, one part causes illness in another. . .. The body is homogeneous (lit. the same as itself) and is composed of the same things, though not in uniform disposition, in its small parts and its large; in parts above and parts below. And if you like to take the smallest part of the body and injure it, the whole body will feel the injury, whatever sort it may be, for this reason, that the smallest part of the body has all the things that the biggest part has.[13]

Hippocrates founded a school of medicine known by his name, and advocated a basic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of disease that still has applications in modern medicine. [For example, see Pappas et al.[14], Chang et al.[15], and Ghaemi[16]]

Why do modern day researchers keep going back to Hippocrates?....although ancient, some notions expressed in the Hippocratic works are still applicable today. What is more important though, is a reason easily recognized to anyone familiar with Hippocratic descriptions of infection: the clarity of presentation of the clinical course and the astute inclusion of infection in a broader environmental and social context are still unparalleled by modern thinking.[14]

History gave his name to an oath of medical ethics called the Hippocratic Oath. "The code of conduct for doctors outlined in the Hippocratic Oath, a vow commonly taken by modern doctors", remains an ethical guideline in medicine.[17] One can begin to appreciate the influence of Hippocrates to the present day by his presence in the World Wide Web since the year 2000, where the scientific search engine, SCIRUS, reveals 74,523 entries, and Google search reveals ~172,000 entries for the twelve months preceding April 2008.

Early Greek medicine operated as a supernatural, magical art. The god of healing, Asclepius (Aesculapius in Roman terminology), [18] whose priests and temples flourished in ancient Greece at least from the Homeric era, appeared in the dreams of the sick who came to the temple for 'sleep therapy'. Asclepius gave advice to the dreamer, which the priests interpreted. The priests prescribed baths, diets, exercises, changes in occupation or living locales, and other routines, and those prescriptions received credit when cures occurred. The cult of ‘therapeutic dreaming’ persisted in various places even into Christian times.[19]

Hippocratic medicine developed as the "naturalistic counterpart" of the Asclepian supernaturalistic tradition.[20] By the 6th century BCE (the 500s BCE) Greek philosophers emerged and began to theorize about the natural causes of the way the world worked. Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), characterized as a physician and philosopher, postulated earth, air, fire and water as the primordial elements of which everything in the world consisted, in differing combinations and kinds of combinations, including the human body.[21] [22]

The development of Hippocratic medicine, its [Aesculapian medicine’s] naturalistic counterpart, is considered a turning point in the history of the healing arts although, as we have seen, at about the same time, naturalistic medical paradigms were developing in other ancient civilizations as well. The importance of Hippocratic medicine rests on the fact that it is the first comprehensive naturalistic medical system of the Western world and therefore the source from which scientific medicine would eventually originate.[20]

Indeed, the development of Hippocratic medicine may have influenced changes in the persisting Asclepian practice.[23]

For its objectives of seeking classification, causes and remedies of disease, medicine requires reason, but not only reason. Considering that knowledge emerges from information processed by reason, not only does the quality of reason count, but also does the quality of the information fed into reason count. Reason will yield a formally valid conclusion, but if fed flawed information, it will not yield a reliable conclusion. For the latter, reason requires information ultimately based on empirically sound observation. If based on wishful thinking, imagination, unquestioned assumptions, believed revelation by deities, guesswork and the like, reason yields at best dubious knowledge and at worst false knowledge. Hippocrates appears to have understood that, and as a physician considered to epitomize the art of medicine, as Socrates did, he inspired many likeminded and knowledge-seeking followers.

Likely inspired by Empedocles’ concept of four elements making up natural things,[24] the concept of four humours (blood, yellow bile, black bile, phlegm) as constituent elements of the human body emerged as part of the Hippocratic tradition, the individual humours in various combinations determining state of health and personality:

- excess blood makes a person ‘sanguine’, full of energy, optimistic, ruddy complected

- excess yellow bile makes a person ‘bilious’, ‘choleric’, bad tempered, quick to anger, irritable

- excess black bile makes a person ‘melancholic’, deeply and long-lastingly sad

- excess phlegm makes a person ‘phlegmatic’, unemotional, temperamentally slow, calm

Historians have not identified an individual who originated the four humours theory, nor have they excluded the possibility that the theory emerged into a formal theory only gradually. [25]

The medical corollary of Empedocles' theory is the identification of the traditional humours with constituent elements: what made this possible was the presence, in the traditional view of humours, of positive characteristics. Because of these characteristics it was easy to conceive the humours as the ingredients of man, upon which his normal or healthy state, as well as his very existence, depended….It is not the recognition of this or that humour as existing which counts, but the theoretical use to which that humour is put. One would therefore also have to find evidence….that the humours were regarded as constituent parts of the human body. There seems no a priori reason why this should not have been the case, in any writer working after say 450. But in the absence of such evidence, the question of the precise originator of the four-humoral theory is formally insoluble….What is perhaps of more interest is the way in which the theory of four humours exemplifies the stimulating effects of Greek philosophy on Greek medical science. It may be described in this way: the philosopher provides the categories within which the medical scientist can order his experience. (Page 61) [25]

The Hippocratic physician: scientist or craftsman?

H.J.F. Horstmanshoff argues that the Hippocratic physicians qualify as craftsmen, and not as scientists:

Ancient physicians did not receive scholarly, scientific training. The intellectual attitudes and social status which we are inclined to attribute to them are anachronisms nourished by the Hippocratic tradition from Galen to Littre. Physicians who had scholarly ambitions steered toward philosophy and rhetoric rather than to empirical disciplines. As a consequence of the prevailing social and economic outlook, the image of the rhetor [teacher of rhetoric, or orator] and of the philosopher were considered to be far better than that of the engineer or of the artisan, or that of those devoted to applied knowledge in general. Ancient physicians were above all craftsmen. Nevertheless the more ambitious among them cloaked over the manual aspects of their art and explained away the remuneration for their services with the help of rhetoric [persuasive public speaking].[26]

....

Social and economic roles of the Hippocratic physicians

The Hippocratic Corpus records a wealth of information about classical Greek medicine, yet records little details about the lives of the Hippocratic physicians. In part to remedy that gap, or compensate in a way for it, classical scholar, Hui-hua Chang studied the Greek cities in the northern regions of the Aegean where the Hippocratic physicians spent time, as recorded in the Hippocratic treatise, Epidemics.[27] The express purpose of the study, according to Professor Chang, “…is to determine how such places may help us define the social and economic roles of Greek physicians in the Classical period.”

Professor Chang's analysis reveals that one mischaracterizes the Hippocratic physicians as mere aimless itinerants, as sometimes implied by writers. Rather, more objectively, Chang characterizes them as physicians visiting targeted towns and villages for specific reasons of seeking employment and financial support as opportunity presented. They found greater job opportunities in the larger urban centers where division of labor accompanied by specialization of occupation had already evolved. Moreover, such centers housed wealthy individuals and families who could support the renown Hippocratic physicians of burgeoning repute.

Professor Chang provides detailed descriptions of the cities visited by the Hippocratic physicians, their location on trade routes, their chiefs sources of trade, their resources for their daily lives — revealing most of them as wealthy commercial centers or the major cities in the region. He describes:

- Cyzicus on the southern coast of Propontis (now the Sea of Marmara) — visible upper right on the accompanying map south of Thrace and North of Asia Minor (Anatolia) — acquiring its wealth from its location on the trade route between the Black Sea to the northeast and the Aegean Sea to the west, its exports of wine, fish and marble, and it supply of wheat to the Aegean from Russia.

- Perinthis on the northern coast of Propontis, also depicted on the map, a trade city with abundant territory to produce corn, cattle and timber.

- Abdera and Ainos, on the Thracian coast near the island of Thrasos in the north Thracian Sea. Ainos acquired its wealth from its location at the mouth of the major river in the northern Aegean, supplying the Aegean with the products fertile Thracian fields in return for Greek merchandise. Abdera — home of the geometer and atomist, Democritus, whom legend has it Hippocrates visited because of accusations of mental dysfunction and declared Democritus the sanest man in town — became “the emporium of the silver trade”.

- Thrasos, the island and its Thracian mainland colonies, wealthy from gold and silver mining and producing wine considered the finest in Greece. The Hippocratic physicians spent much time in Thrasos.

- Olynthus, the largest city on the peninsula of Chalcidice, visible on the map in the southern part of Macedonia, destroyed after Hippocrates’ death because Phillip II considered it a threat to his rule of Macedonia. The Hippocratic physicians practiced their art there prior to its destruction, when its large population displayed their wealth and power.

- Larissa, in Thessaly, south of Macedonia and left of center on the map, shows up in Epidemics with many descriptions of medical cases. It had much fertile land and control of the mountain passes to Macedonia.

Possibly the Hippocratic favored those cities both because their wealth and the undoubted wealth of patients in cities with dense populations of people living luxuriously. Large populations also usually meant labor division and thus opportunities for physicians to concentrate on practicing medicine. Professor Chang closes thus:

It was in such places as those described above, where wealth was concentrated and people with open minds resided, that they [the Hippocratic physicians] would find clients and patrons who were ready to accept untraditional [non-supernatural] ideas and who would support the art of the Hippocratic doctors.[27]

The Hippocratic treatises

This listing as in Jouanna's Appendix 3.[5] Jouanna states: "The principal editions given here are based on the Greek-French edition of Émile Littré (10 vols., 1839-1861).[5]

|

|

....

Aphorisms

The first aphorism

|

"....the First Aphorism is medicine’s whole law; the rest is commentary." |

Of the more than 400 aphorisms attributed to Hippocrates, the first has received the most attention. In the Francis Adams translation,[30] it reads:

Life is short, and the Art long; the occasion fleeting; experience fallacious; and judgment difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and the externals cooperate.[30]

Another 19th century translation:[31]

Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.>[31]

The same aphorism as translated in the Hippocratic Writings edited by G. E. R. Lloyd reads:[32]

Life is short, science is long; opportunity is elusive, experiment is dangerous, judgement is difficult. It is not enough for the physician to do what is necessary, but the patient and the attendants must do their part as well, and circumstances must be favourable.[32]

In the Adams translation, the "Art", always with an capital 'A', refers to medicine — the art of medicine. In the Lloyd text, the 'Art of medicine' becomes 'science'. In either case, the first clause of the first aphorism seems to say that the lifespan of a physician does not suffice for learning the Art of medicine, all of its science. The implication would seem to exhort awareness to physicians that they cannot expect learn all of medicine in a lifetime, an exhortation to humility and avoidance of overconfidence. Can any physician even two and a half millenia later deny the aphorism, especially in respect of the enormous amount and intricate complexity of the knowledge base of medicine in the early 21st century. Perhaps the complete Art of medicine will always overwhelm any one physician's lifetime of learning and practice.

Sherwin Nuland puts it this way:

Although life expectancy is currently well more than twice what it was during the golden age of Greece, it will never be endowed with years enough for anyone to master the vast expanse of medical knowledge, or even that part of it sufficient for an individual doctor to care for all of his patients.[29]

The aphorism continues with the occasion fleeting, alternatively opportunity is elusive, generally interpreted as indicating the need for timely diagnosis to achieve the best results of treatment — a narrow window of opportunity.

[E]xperience fallacious, or experiment [in the sense of experience] is dangerous, seems to warn of misinterpreting the patient's symptoms and signs by relying on experience that might apply generally but not to the specific patient at hand owing to that patient's particular circumstances, internal or external, physiological or psychological. Sherwin Nuland applies that to the non-personal 'experience' that statistics offers, unless it takes into consideration individual variability and the factors that go into generating it.

[J]udgment is difficult seems to follow give that life is short and the art, and that experience of other cases cannot always be counted as reliable when applied to an individual patient at hand.

21st century scholarly interest in and diversity of views of Hippocrates

- Some Abstracts paragraphed or otherwise reformatted for ease of reading

- Grammaticos PC, Diamantis A. (2008) [From Emeritus professors, Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece] [33]

|

“Hippocrates is considered to be the father of modern medicine because in his books, which are more than 70. He described in a scientific manner, many diseases and their treatment after detailed observation. He lived about 2400 years ago. He was born in the island of Kos and died at the outskirts of Larissa at the age of 104. Hippocrates taught and wrote under the shade of a big plane tree, its descendant now is believed to be 500 years old, the oldest tree in Europe-platanus orientalis Hippocraticus- with a diameter of 15 meters.”

He used as a pain relief, the abstract from a tree containing what he called "salycasia", like aspirin. He described for the first time epilepsy not as a sacred disease, as was considered at those times, but as a hereditary disease of the brain and added: "Do not cut the temporal place, because spasms shall occur on the opposite area". According to Hippocrates, people on those times had either one or two meals (lunch and dinner). He also suggested:

References and notes cited in text

|