Energy policy and global warming

Climate scientists tell us that our consumption of fossil fuels is raising atmospheric CO2 levels, causing rapid global warming, and risking catastrophic climate change.[1] Most people now accept these conclusions, but there is still debate over whether the replacement for fossil fuels should include nuclear power. Many believe that nuclear power cannot be made safe and clean. See Nuclear power reconsidered for discussion of these concerns. Others believe that an energy policy that does not include nuclear is unrealistic. This article is a brief review of the options for decarbonizing our world.

The Magnitude of the Problem

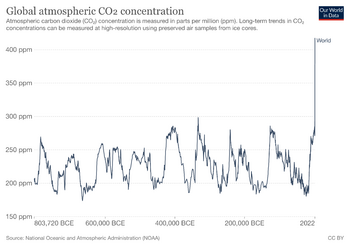

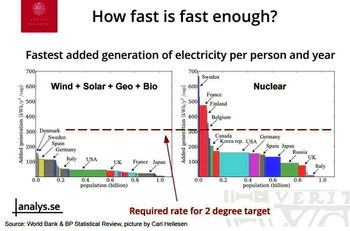

Over millions of years, the Earth has developed an equilibrium between the carbon in the atmosphere and in the rocks and organic material on or near the surface. That equilibrium is now being radically altered by our consumption of fossil fuels. What seems to us like a slow change over decades, is a vertical spike in Fig.1. That spike is continuing to shoot upwards in spite of years of talk and negotiations among the world's nations, and failure to reach agreed on targets. The CO2 we put in the atmosphere now will last for centuries.[2] To minimize the risk of a catastrophic change in climate,[3] scientists are telling us we need to limit global warming to 2 degrees C.[4] That will require ten times more CO2 reduction than even the optimistic targets in current agreements. Clearly we need a new strategy.

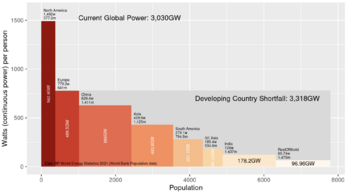

The major contributors to our total CO2 emissions include heat for buildings and industrial processes, fuels for transportation, and electric power. Fig.2 shows our current total worldwide consumption of electric power, with each bar a different region on our planet. The height of the bar is the average per person, and the width is the population of each region, so the area of the bar is a good visualization of total consumption for a region. The developing countries are expected to increase their consumption, perhaps to the level of Europe, or half the level of North America. That will put the total worldwide average power at 6300 GW, or more than twice our current level.

A Plan for the Future

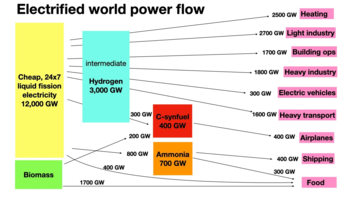

One vision for the future is using nuclear power to replace all fossil fuel power as in Fig.3. Abundant carbon-free power could be used to generate a mix of electric power and hydrogen appropriate for each sector of the economy. Home and office heating could be electrical or hydrogen piped through existing networks. District heating over short distances could be provided more efficiently by piping the reactor heat directly to nearby buildings. Industrial processes could also use heat from the reactors, especially the low-cost heat available during off hours. Energy for transportation could be electrical for light vehicles, and hydrogen for larger vehicles and rail. Synthetic fuel could be generated for airplanes and any other vehicles that truly need the compact energy of fossil fuels. Ocean shipping could be fueled with ammonia, one-third the energy density of fossil fuels.

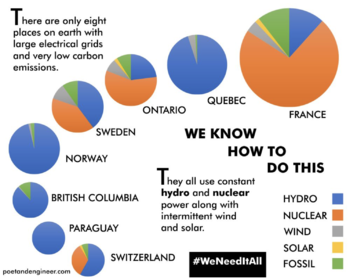

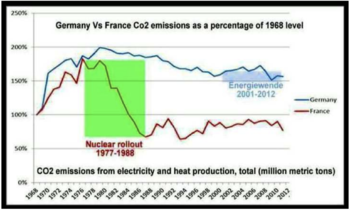

A plan like that in Fig.3 may take decades to fully implement, but decarbonizing our electrical grids could be done immediately, using current wind, solar, and nuclear technology. Several nations have already done it (Fig.4).

The Problems with Wind and Solar Alone

- need for 100% fossil fuel backup - Fig.5

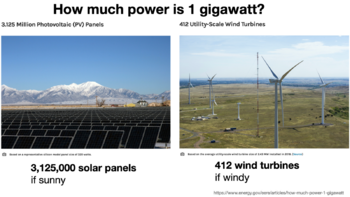

- use of land and mineral resources - Fig.6, 7

The Need for Immediate Action

Fig.8,9

Further Reading

Electrifying Our World Robert Hargraves' excellent overview of energy, the growth human civilization, and possible solutions to the current climate crisis.

Our World in Data has a section on Energy and Environment with nice interactive graphics.

World Nuclear Information Library a well-organized authoritative collection of information on nuclear power.

Notes and References

- ↑ IPCC Sixth Assessment Report - Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

- ↑ Carbon is Forever, M.Inman, Nature 2008.

- ↑ One scary scenario involves a "positive feedback" mechanism in which the permafrost in the polar regions starts to thaw, releasing methane trapped for millions of years. The methane is 80 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas. This warms the permafrost further, and we could get a runaway condition with no escape, even if we cut our CO2 emissions to zero.

- ↑ UN Environment Emissions Gap Reports