Jesus

Jesus (or Jesus Christ) was a Palestinian Jewish religious figure who was executed by the Roman government by crucifixion around AD 30 or 33. He is chiefly remembered as the (perhaps unwitting) founder of Christianity, and as a prophet of Islam.

Almost every aspect of his life is either unknown or disputed. A minimalist view would accept the description of Jesus as a wandering, charismatic teacher active around Galilee and Judea. He received baptism from John the Baptist; spoke before crowds; performed spiritual healings and exorcisms (setting aside the question of whether any supernatural aspect was involved); and attracted disciples.

Christian tradition adds that his mother Mary was a Virgin; that he performed miracles; that he claimed to be, and was, the Messiah (Greek Christos, the source of the title Christ); that his life fulfilled Old Testament prophecies; and that he rose from the dead and ascended into heaven, from whence he will one day return. Most Christians worship Jesus as the Son of God, and as God incarnate, the Second Person of the Trinity, and look to him for the salvation of their souls.

The Qur'an recognizes Jesus (Arabic Isa) as one of the most important prophets of Islam, and as a bringer of a divine scripture (which is not necessarily part of the extant New Testament). Muslims accept the Virgin Birth, and agree that Jesus is the messiah, but reject any attribution of divinity to him. Many Muslims doubt the crucifixion, and hold that Jesus will return to the earth in the company of the Mahdi.

Thanks largely to his role in Christianity, Jesus has become one of the most consequential individuals who ever lived. Stripped of this religious heritage, the history of European art and music would be unimaginable. Translations of the Christian Bible number among the foundational literature of numerous languages, including English. Events in Jesus's life are commemorated through vast public holidays such as Christmas and Easter. Most of the world now follows the Gregorian calendar, which attempts to calculate the number of years elapsed since Jesus's birth.

The Historical Jesus

Since the Enlightenment, various scholars have attempted to distinguish Jesus as a historical figure, from the figure worshipped by Christianity. Initial projects were motivated by rationalism and focused doubt on biblical accounts of miracles.

Gradually other aspects of the gospels and church doctrine fell under suspicion. For example, David Friedrich Strauss and Ernest Renan saw Jesus as a great moral teacher whose views are best represented by the Sermon on the Mount. Albert Schweizer, objecting to the arbitrary neglect of apocalyptic verses, complains that scholars who set out on a search for the "historical Jesus" tend to discover in him a reflection of their own views.

In recent decades the name "Jesus Studies" has come to describe historical (as opposed to primarily theological) approaches to the study of Jesus. Scholars in this field fall into much the same religious divisions as the wider population, though relative iconoclasts (e.g. the Jesus Seminar, treated collectively) may be somewhat more visible.

Sources

The major historical difficulty concerning Jesus is that the most important sources of information, the four canonical gospels, are works of sectarian propaganda. As historical sources, they suffer from the following shortcomings:

- Their authors are not known (despite the titles assigned to them by church tradition); thus we have no way of knowing whether or how an author acquired his information.

- Their composition appears to involve multiple authorship (e.g., the synoptic gospels share much material, albeit rearranged) and an active editorial process.

- They appear to have been written at least a generation after Jesus's death. ( Mark, the oldest, is usually dated around AD 68.)

- No first-century mss are extant.

- They report numerous supernatural events, which in the eyes of many historians is prima facia evidence of their unreliability.

- Their authors were obviously committed believers, not disinterested observers.

- Some details (such as the Census of Quirinius mentioned in Luke 2:1) conflict with what we know of the history of the time.

- They show signs of adapting their stories to make theological points. For example, Matthew (21:1 ff) describes Jesus as entering Jerusalem while seated on not one but two animals, a donkey and a colt--an unlikely mode of transport which seems to represent a misunderstanding of Zachariah 9:9, (which Matthew quotes).

- Some stories appear to have been inspired by Old Testament prototypes. For example, Christ's miracles in Matthew 8 and 9 parallel the miracles of Elisha in 2 Kings 4 - 6.

Aside from the canonical gospels, several ancient authors who were not Christians (Flavius Josephus, Pliny the Younger) mention Jesus; however, their knowledge is likely to be second-hand. Saint Paul apparently met some of Jesus's relatives and companions (though not Jesus himself); unfortunately, his epistles offer almost no biographical details.

Noncanonical Christian literature is voluminous but relatively late, with the following possible exceptions: the Gospel of Thomas, the Unknown Berlin Gospel, the Oxyrhynchus Gospels, the Egerton Gospel, the Fayyum Fragment, the Dialogue of the Saviour, the Gospel of the Ebionites, the Gospel of the Hebrews, and the Gospel of the Nazarenes. While the earliest surviving manuscripts and fragments of these texts are dated later than the earliest surviving manuscripts and fragments of the canonical Gospels, they are probably copies of earlier manuscripts whose precise dates are unknown.

Many scholars point to a hypothetical, reconstructed text called "Q" (from the German Quelle, meaning "source") as a possible older substratum which might bridge the gap between the time of Jesus and the composition of the gospels. This influential documentary hypothesis is based on the synoptic problem, i.e. the fact that the three synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) share much material in common. In particular, Matthew and Luke each include almost the whole of Mark's material (and are each about twice as long as Mark), suggesting that Mark came first, and was then incorporated into Matthew and Luke. However, Matthew and Luke also share other material not found in Mark, suggesting to some the two-source hypothesis, namely that they were also copying from another, no longer extant text. Thus "Q" is defined as anything which is in Matthew and Luke, but not in Mark. As it happens, this material consists largely of sayings of Jesus--exactly the sort of document one would expect to have been composed at an early date in the history of Christianity. (The Gospel of Thomas follows this pattern, being a collection of logoi.) The assumption is that Jesus lore would have circulated as oral tradition and collections of written logoi prior to its incorporation into the gospels.

Another theoretical document is the Signs Gospel, believed to have been a source for the Gospel of John.

Minimalist Views

Such problems with sources have led a few scholars to deny that Jesus ever existed at all. In this view, the story of Jesus would be entirely mythical, of a piece with various other Near Eastern deities or demigods (e.g. Mithras, Apollo, Attis, Horus, Osiris-Dionysus) who experienced virgin birth and / or resurrection from the dead. This view, however, has not won wide support.

A major counter-argument is the criterion of embarrassment. This principle holds that a gospel detail which early Christians would have found embarrassing, is more likely to be true. An example would be Jesus's execution as a criminal, a rather disturbing element not included in any known Jewish traditions of the messiah. Were Jesus entirely fictional, his story would surely have ended differently. Therefore (a) Jesus really was executed, and as a corollary, (b) Jesus really existed.

Jesus's baptism by John is another example. This detail would have been embarrassing to early Christians because of (a) the implicit suggestion that Jesus had sins to be forgiven, and (b) the inferior role of Jesus viz. John. Matthew (3:13-15) even has John object to the arrangement, only to hear Jesus insist. All four gospels stress John's expectation of another greater than himself, as if this were a point that required emphasis. In this connection, the Mandaeans of southern Iraq are a gnostic sect which venerates John but not Jesus, whom they regard as a schismatic who abandoned the Baptist movement.

Other details that arguably fit the criterion would include Jesus's statement (Mark 10: 18, cf. Luke 18:19) "Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone." (Jesus's intent could be interpreted in different ways, however.)

Jesus in Context

Scholars in the field of Jesus Studies describe Jesus in various ways, generally with reference to such aspects of the gospels and other sources as they deem probable, and to external historical and archeological information about the time and place in which he lived. A list of some prominent scholars, together with summaries of their work, can be found here.

One

On the Impossibility of a Chronology

The gospels do not say when Jesus was born, when he died, or his age at death. (Church tradition reports that he began his ministry at age 30, on the grounds that this was the ideal human age, and was killed three years later.) Those details which can be dated, often appear to conflict with one another.

For that matter, the gospels sometimes disagree as to the sequence of events. One theory is that the synoptic gospels were constructed around several ancient church calendars, with an eye to providing teaching material to complement the Torah readings for each week. If true, this would devastate the attempt to tease from the gospels a chronology of Jesus's life, as the sequence would turn out to be based on extra-historical thematic considerations.

The exact date of Jesus' death is also unclear. Many scholars hold that the Gospel of John depicts the crucifixion just before the Passover festival on Friday 14 Nisan, called the Quartodeciman, whereas the synoptic gospels (except for Mark 14:2) describe the Last Supper, immediately before Jesus' arrest, as the Passover meal on Friday 15 Nisan; however, a number of scholars hold that the synoptic account is harmonious with the account in John.[1] Further, the Jews followed a lunisolar calendar with phases of the moon as dates, complicating calculations of any exact date in a solar calendar. According to John P. Meier's A Marginal Jew, allowing for the time of the procuratorship of Pontius Pilate and the dates of the Passover in those years, his death can be placed most probably on April 7, 30 AD/CE or April 3, 33 AD/CE.[2]

Birth

The Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke contain nativity stories, which are often conflated for the purpose of popular commemoration through Christmas creches and the like. (The magi are from Matthew 2; the angels and shepherds are from Luke 2; and the animals surrounding the manger do not appear at all.) Neither the Census of Querinius nor Herod's "massacre of the innocents" appear to have actually happened.

As for Jesus's birthplace, the gospels often refer to him as a Galilean, which fits the criterion of embarrassment. Nazareth is in fact in Galilee, or near enough, but it might not have existed during the first century. Some have argued that the title Iesos Nazarenos should be translated "Jesus the Nazarene" rather than "Jesus of Nazareth." Skeptics dismiss Luke's story about Jesus being born in Bethlehem as a transparent attempt to link him to King David, who was born there.

- Luke's shepherds tend their flocks in the fields, suggesting a spring or summer date.

In Western Christianity, it has been traditionally celebrated in the liturgical season of Christmastide as Christmas on 25 December, a date that can be traced as early as 330 among Roman Christians. Before then, and still today in Eastern Christianity, Jesus' birth was generally celebrated on January 6 as part of the feast of [[Theophany, also known as Epiphany, which commemorated not only Jesus' birth but also his baptism by John in the Jordan River. Scholars speculate that the date of the celebration was moved in an attempt to replace the Roman festival of Saturnalia (or more specifically, the birthday of the God Sol Invictus).

In the 248th year during the Diocletian Era (based on Diocletian's ascension to the Roman throne), Dionysius Exiguus attempted to pinpoint the number of years since Jesus' birth, arriving at a figure of 753 years after the founding of Rome. Dionysius then set Jesus' birth as being December 25 1 ACN (for "Ante Christum Natum", or "before the birth of Christ"), and assigned AD 1 to the following year — thereby establishing the system of numbering years from the birth of Jesus: Anno Domini (which translates as "in the year of our Lord"). This system made the then current year 532, and almost two centuries later it won acceptance and became the established calendar in Western civilization due to its further championing by the Venerable Bede.

Family

Matthew 1:1 ff and Luke 3: 23 ff give accounts of Jesus's genealogy which appear contradictory, though several theories attempting to harmonize them have been proposed. Matthew pointedly traces Jesus's ancestry to Abraham and King David; Luke, to God by way of Adam. The names on the two lists diverge after the time of David. Skeptics note that cross-culturally, such geneaologies are often fictitious; and that many of the characters listed here appear to be mythical. Oddly, the same gospels affirm that Jesus's true father was God rather than Joseph, whose ancestry they take such pains to recount. Perhaps a legal rather than genetic relationship (as with adoption) is being described here.

The gospels agree on the names of Jesus's parents, Mary and Joseph. Since Joseph appears only in descriptions of Jesus' childhood, whereas Mary is present at the crucifixion, this has led some Christians to speculate that Joseph had died during the intervening years.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus entrusts the care of his mother to the "beloved disciple" (whom tradition often conflates with John). If historical, this suggests that he had no surviving male relatives. However, Matthew 13:55-56 and Mark 6:3 (cf. Galatians 1: 19) name several "brothers" (adelphoi) and allude to sisters as well. Orthodox and Catholic Christians insist that some other familial or affectional relationship is meant, as according to their belief, Mary remained a lifelong virgin, with Jesus as her only child.

Historically, Jesus's "brother," Jakob ha-Zaddik (anglicized as "James the Righteous") led the Jerusalem church from

The gospels do not say whether Jesus was married. While Jewish tradition discourages celibacy, exceptions might exist for special situations such as war, and some Jewish groups (such as the Essenes) did practice it on this basis. A number of modern writers, some of them scholarly, speculate that Mary Magdalene was his wife. The Secret Gospel of Mark--rejected by many as a 20th century fraud--hints that Jesus practiced ritual homosexuality. Mormon tradition holds that Jesus was (and remains) plurally married, to Mary and Martha.

Appearance

Occupation

Teachings

One key issue which defies consensus is that of Jesus's teachings. Scholars researching the historical Jesus have arrived at a variety of conclusions:

Death

(Temporary Trash Can)

The Gospels record that Jesus was a Nazarene, but the meaning of this word is vague.[3] Some scholars assert that Jesus was himself a Pharisee.[4] In Jesus' day, the two main schools of thought among the Pharisees were the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai. Jesus' assertion of hypocrisy may have been directed against the stricter members of the House of Shammai, although he also agreed with their teachings on divorce (Mark 10:1–12).[5] Jesus also commented on the House of Hillel's teachings (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 31a) concerning the greatest commandment (Mark 12:28–34) and the Golden Rule (Matt 7:12).

Other scholars assert that Jesus was an Essene, a sect of Judaism not mentioned in the New Testament.[6] Still other scholars assert that Jesus led a new apocalyptic sect, possibly related to John the Baptist,[7] which became Early Christianity after the Great Commission spread his teachings to the Gentiles.[8] This is distinct from an earlier commission Jesus gave to the twelve Apostles, limited to "the lost sheep of Israel" and not including the Gentiles or Samaritans (Matt 10).

Of special interest has been the names and titles ascribed to Jesus. According to most critical historians, Jesus probably lived in Galilee for most of his life and he probably spoke Aramaic and Hebrew.

The name "Jesus" is an English transliteration of the Latin (Iēsus) which in turn comes from the Greek name (Ιησους). Since most scholars hold that Jesus was an Aramaic-speaking Jew living in Galilee around 30 AD/CE, it is highly improbable that he had a Greek personal name. Further examination of the Septuagint finds that the Greek, in turn, is a transliteration of the Hebrew name Yehoshua (יהושוע) (Yeho - Yahweh [is] shua` - help/salvation) or the shortened Hebrew/Aramaic Yeshua or Jeshua (ישוע). As a result, scholars believe that one of these was most likely the name that Jesus was known by during his lifetime by his peers.[9]

Christ (which is a title and not a part of his name) is an Anglicization of the Greek term for Messiah, and literally means "anointed one". Historians have debated what this title might have meant at the time Jesus lived; some historians have suggested that other titles applied to Jesus in the New Testament (e.g. Lord, Son of Man, and Son of God) had meanings in the first century quite different from those meanings ascribed today: see Names and titles of Jesus.

Other important apocryphal works that had a heavy influence in forming traditional Christian beliefs include the Apocalypse of Peter, Protevangelium of James, Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and Acts of Peter. A number of Christian traditions (such as Veronica's veil and the Assumption of Mary) are found not in the canonical gospels but in these and other apocryphal works.

Jesus in Christianity

Within Christianity, the nature of Jesus is the central issue of Christology. For most Christians, Jesus is more than a historical figure who lived and died, but the supreme source of meaning for all humanity. He is said to have existed before the creation of the world, and will reign after its destruction.

Christian beliefs have always been diverse, although many theologians have condemned as heresy beliefs opposed to theirs. The Ebionites, an early Jewish Christian community, believed that Jesus was the last of the prophets and the Messiah. They believed that Jesus was the natural-born son of Mary and Joseph, and thus they rejected the Virgin Birth. The Ebionites were adoptionists, believing that Jesus was not divine, but became the son of God at his baptism. They rejected the Epistles of Paul, believing that Jesus kept the Mosaic Law perfectly and wanted his followers to do the same. However, they felt that Jesus' crucifixion was the ultimate sacrifice, and thus animal sacrifices were no longer necessary. Therefore, some Ebionites were vegetarian and considered both Jesus and John the Baptist to have been vegetarians.[10] Shemayah Phillips founded a small community of modern Ebionites in 1985. These Ebionites identify as Jews rather than as Christians, and do not accept Jesus as the Jewish Messiah.

The name "Gnosticism" has been applied to a vast collection of often unrelated figures and movements. While some Gnostics were docetics, most Gnostics believed that Jesus was a human who became possessed by the spirit of Christ during his baptism.[11] Many Gnostics believed that Christ was an Aeon sent by a higher deity than the evil demiurge who created the material world. Some Gnostics believed that Christ had a syzygy named Sophia. The Gnostics tended to interpret the New Testament as allegory, and some Gnostics interpreted Jesus himself as an allegory. Modern Gnosticism has been a growing religious movement since fifty-two Gnostic texts were rediscovered at Nag Hammadi in 1945. The movement was also given a boost by the publication in 2006 of the Gospel of Judas.

Marcionites were 2nd-century Gentile followers of the Christian theologian Marcion of Sinope. They believed that Jesus rejected the Jewish Scriptures, or at least the parts that were incompatible with his teachings.[12] Seeing a stark contrast between the vengeful God of the Old Testament and the loving God of Jesus, Marcion came to the conclusion that the Jewish God and Jesus were two separate deities. Like some Gnostics, Marcionites saw the Jewish God as the evil creator of the world, and Jesus as the savior from the material world. They also believed Jesus was not human, but instead a completely divine spiritual being whose material body, and thus his crucifixion and death, were divine illusions. Marcion was the first known early Christian to have created a canon, which consisted of ten Pauline epistles, and a version of the Gospel of Luke (possibly without the first two chapters that are in modern versions, and without Jewish references),[13] and his treatise on the Antithesis between the Old and New Testaments. Marcionism was declared a heresy by proto-orthodox Christianity.

The theological concept of Jesus as Christ was refined by a series of ecumenical councils beginning in the fourth century AD, the first and second of which produced the Nicene (or Niceno-Constantinopolitan) Creed:

These councils were convened in an atmosphere of politically-charged theological debate, and their conclusions absolutely do not represent a consensus of Christian views at the time. Indeed, each successive council resulted in some new branch of Christianity falling out of communion with the others: Nestorianism after the third; the non-Chalcedonian churches after the fourth, and so on.

The Orthodox Church accepts seven such councils; the Roman Catholic Church, 2? (the most recent being Vatican II). Mainline Protestants acknowledge at least the Nicene and Apostles Creeds, along with their various confessions. The Baptist churches reject creeds as un-biblical, but would have no serious objection to the

Most Christians believe that Jesus is God incarnate, being one of the three divine persons who make up the single substance of God, a concept known as the Holy Trinity. In this respect, Jesus is both distinct and yet of the same being as God the Father and the God the Holy Spirit.[14] They believe Jesus is the Son of God, and also the Messiah. Following John 1:1, Christians have identified Jesus as "the Word" (or Logos) of God. Most also believe that Jesus' miracles and resurrection are additional proof that he is God. They combine this with the classic proof based on the two rational alternatives in the face of Jesus' repeated claims that he is the one God of Israel (e.g. Jn 8:58): either he is truly God or a bad man (a liar or a lunatic), the latter being dismissed on the basis of Jesus's perceived coherence. [15] Most trinitarian Christians further believe that Jesus has two natures in one person: that he is fully God and fully human, a concept known as the hypostatic union. However, Oriental Orthodoxy professes a Miaphysite interpretation, while the Assyrian Church of the East professes a form of Nestorianism.

Paul of Tarsus wrote that just as sin entered the world through Adam (known as The Fall of Man), so salvation from sin comes through Jesus, the second Adam (Rom 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:21–22). Most Christians believe that Jesus' death and resurrection provide salvation not only from personal sin, but from the condition of sin itself. This ancestral or original sin[16] separated humanity from God, making all liable to condemnation to eternal punishment in Hell (Rom 3:23). However, Jesus' death and resurrection reconciled humanity with God, granting eternal life in Heaven to the faithful (John 14:2–3).

Nontrinitarian views

Some Christians profess various nontrinitarian views. Arianism, denounced as a heresy by the early Church, taught that Jesus is subordinate to God the Father.[17] Binitarians believe that Jesus is God, although a separate being from God the Father, and that the Holy Spirit is an impersonal force. Unitarian Christians believe that Jesus was a prophet of God, and merely human.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) theology maintains that God the Father (Heavenly Father), Jesus Christ, and the Holy Ghost are three separate and distinct beings who together constitute the Godhead.

Jehovah's Witnesses view the term "Son of God" as an indication of Jesus' importance to the creator and his status as God's "only-begotten (unique, one and only) Son" (John 3:16), the "firstborn of all creation" (Col 1:15), the one "of whom, and through whom, and to whom, are all things" (Rom 11:36). Most Jehovah's Witnesses believe Jesus to be Michael the Archangel, who became a human to come down to earth.[18] They also believe that Jesus died on a single-piece torture stake, not a cross.[19]

Jesus in Islam

In Islam, Jesus (known as Isa in Arabic, Arabic: عيسى), is considered one of God's most-beloved and important prophets and the Messiah.[20] Like Christian writings, the seventh-century Qur'an holds that Jesus was born without a biological father to the virgin Mary, by the will of God (in Arabic, Allah) and for this reason is referred to as Isa ibn Maryam (English: Jesus son of Mary), a matronymic (since he had no biological father). (Qur'an Template:Quran-usc, Template:Quran-usc, Template:Quran-usc, Template:Quran-usc) In Muslim traditions, Jesus lived a perfect life of nonviolence, showing kindness to humans and animals (similar to the other Islamic prophets), without material possessions, and abstaining from sin.[21] Most Muslims believe that Jesus abstained from alcohol, and many believe that he also abstained from eating animal flesh. Similarly, Islamic belief also holds that Jesus could perform miracles, but only by the will of God. [22] However, Muslims do not believe Jesus to have divine nature as God nor as the Son of God. Islam greatly separates the status of creatures from the status of the creator and warns against believing that Jesus was divine. (Qu'ran Template:Quran-usc, Template:Quran-usc, Template:Quran-usc-range). Muslims believe that Jesus received a gospel from God called the Injil in Arabic that corresponds to the Christian New Testament, but that some parts of it have been misinterpreted, misrepresented, passed over, or textually distorted over time so that they no longer accurately represent God's original message to mankind (See Tahrif).[23]

Muslims also do not believe in Jesus' sacrificial role, nor do they believe that Jesus died on the cross. In fact, Islam does not accept any human sacrifice for sin (See Islamic conceptions of atonement for sin for further information). Regarding the crucifixion, the Qur'an states that Jesus' death was merely an illusion of God to deceive his enemies, and that Jesus ascended to heaven.[20] (Qur'an Template:Quran-usc-range.) Based on the quotes attributed to Muhammad, some Muslims believe that Jesus will return to the world in the flesh following Imam Mahdi to defeat the Dajjal (an Antichrist-like figure, translated as "Deceiver"). [24] Muslims believe he will descend at Damascus, presently in Syria, once the world has become filled with sin, deception, and injustice; he will then live out the rest of his natural life. Sunni Muslims believe that after his death, Jesus will be buried alongside Muhammad in Medina, presently in Saudi Arabia. [25] However, the sects of Sunni and Shi'ite Islam are divided over this issue. Some Islamic scholars like Javed Ahmed Ghamidi and Amin Ahsan Islahi question quotes attributed to Muhammad regarding a second coming of Jesus, as they believe it is against different verses of the Qur'an.[26][27][28]

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Movement (accounting for a very small percentage of the total Muslim population) believes that Jesus survived the crucifixion and later travelled to Kashmir, where he lived and died as a prophet under the name of Yuz Asaf (whose grave they identify in Srinagar).[29] Mainstream Muslims, however, consider these views heretical. Also, historical research found these accounts to be without foundation.[30]

Jewish views of Jesus

Judaism considers the idea of Jesus being God, or part of a Trinity, or a mediator to God, as heresy.(Emunoth ve-Deoth, II:5) Judaism also does not consider Jesus to be the Messiah primarily because he did not fulfill the Messianic prophecies of the Tanakh, nor embodied the personal qualifications of the Messiah.[31]

The Mishneh Torah (an authoritative work of Jewish law) states:

Even Jesus the Nazarene who imagined that he would be Messiah and was killed by the court, was already prophesied by Daniel. So that it was said, “And the members of the outlaws of your nation would be carried to make a (prophetic) vision stand. And they stumbled” (Daniel 11.14). Because, is there a greater stumbling-block than this one? So that all of the prophets spoke that the Messiah redeems Israel, and saves them, and gathers their banished ones, and strengthens their commandments. And this one caused (nations) to destroy Israel by sword, and to scatter their remnant, and to humiliate them, and to exchange the Torah, and to make the majority of the world err to serve a divinity besides God. However, the thoughts of the Creator of the world — there is no force in a human to attain them because our ways are not God's ways, and our thoughts not God's thoughts. And all these things of Jesus the Nazarene, and of (Muhammad) the Ishmaelite who stood after him — there is no (purpose) but to straighten out the way for the King Messiah, and to restore all the world to serve God together. So that it is said, “Because then I will turn toward the nations (giving them) a clear lip, to call all of them in the name of God and to serve God (shoulder to shoulder as) one shoulder.” (Zephaniah 3.9). Look how all the world already becomes full of the things of the Messiah, and the things of the Torah, and the things of the commandments! And these things spread among the far islands and among the many nations uncircumcised of heart. (Hilkhot Melakhim 11:10–12)[32]

Reform Judaism, the modern progressive movement, states For us in the Jewish community anyone who claims that Jesus is their savior is no longer a Jew and is an apostate. (Contemporary American Reform Responsa, #68).[33]

According to Jewish tradition, there were no more prophets after 420 BC/BCE, Malachi being the last prophet, who lived centuries before Jesus. Judaism states that Jesus did not fulfill the requirements set by the Torah to prove that he was a prophet. Even if Jesus had produced such a sign, Judaism states that no prophet or dreamer can contradict the laws already stated in the Torah (Deut 13:1–5)[34]

Mandaeanism regards Jesus as a deceiving prophet (mšiha kdaba) of the false Jewish god Adunay, and an opponent of the good prophet John the Baptist, although they do believe that John baptized Jesus.

The New Age movement entertains a wide variety of views on Jesus, with some representatives (such as A Course In Miracles) going so far as to trance-channel him. Many recognize him as a "great teacher" (or "Ascended Master") similar to Buddha, and teach that Christhood is something that all may attain. At the same time, many New Age teachings, such as reincarnation, appear to reflect a certain discomfort with traditional Christianity. Numerous New Age subgroups claim Jesus as a supporter, often incorporating contrasts with or protests against the Christian mainstream. Thus, for example, Theosophy and its offshoots have Jesus studying esotericism in the Himalayas or Egypt during his "lost years."

There are others who emphasize Jesus' moral teachings. Many humanists, atheists and agnostics empathize with these moral principles. Thomas Jefferson, one of the Founding Fathers that many consider to have been a deist, created a "Jefferson Bible" for the Indians entitled "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth" that included only Jesus' ethical teachings.

Legacy

Cultural effect of Jesus

- See also: Images of Jesus, Dramatic portrayals of Jesus, and Jesus in popular culture

According to most Christian interpretations of the Bible, the theme of Jesus' preachings was that of repentance, forgiveness of sin, grace, and the coming of the Kingdom of God. Jesus extensively trained disciples who, after his death, interpreted and spread his teachings. Within a few decades his followers comprised a religion clearly distinct from Judaism. Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire under a version known as Nicene Christianity and became the state religion under Constantine the Great. Over the centuries, it spread to most of Europe, and around the world.

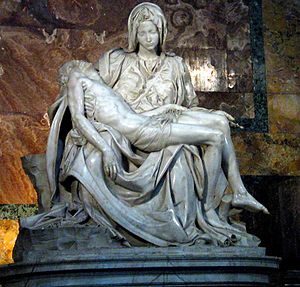

Jesus has been drawn, painted, sculpted, and portrayed on stage and in films in many different ways, both serious and humorous. In fact most medieval art and literature, and many since, were centered around the figure of Jesus. A number of popular novels, such as The Da Vinci Code, have also portrayed various ideas about Jesus. Many of the sayings attributed to Jesus have become part of the culture of Western civilization. There are many items purported to be relics of Jesus, of which the most famous are the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo.

Other legacies include a view of God as more fatherly, merciful, and more forgiving, and the growth of a belief in an afterlife and in the resurrection of the dead. His teaching promoted the value of those who had commonly been regarded as inferior: women, the poor, ethnic outsiders, children, prostitutes, the sick, prisoners, etc. Jesus and his message have been interpreted, explained and understood by many people. Jesus has been explained notably by Paul of Tarsus, Augustine of Hippo, Martin Luther, and more recently by C.S. Lewis.

For some, the legacy of Jesus has been a long history of Christian anti-Semitism, although in the wake of the Holocaust many Christian groups have gone to considerable lengths to reconcile with Jews and to promote inter-faith dialogue and mutual respect. For others, Christianity has often been linked to European colonialism (see British Empire, Portuguese Empire, Spanish Empire, French colonial empire, Dutch colonial empire); conversely, Christians have often found themselves as oppressed minorities in Asia, the Middle East, and in the Maghreb.

Notes

- ↑ See Leon Morris, The Gospel According to John, Revised, pp. 284-295, for a discussion of several alternate theories with references.

- ↑ Meier, p.1:402

- ↑ For a general comparison of Jesus' teachings to other schools of first century Judaism, see John P. Meier, Companions and Competitors (A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume 3) Anchor Bible, 2001. ISBN 0-385-46993-4.

- ↑ Based on a comparison of the Gospels with the Talmud and other Jewish literature. Sanders, E. P. Jesus and Judaism, Fortress Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8006-2061-5; Maccoby, Hyam Jesus the Pharisee, Scm Press, 2003. ISBN 0-334-02914-7; Falk, Harvey Jesus the Pharisee: A New Look at the Jewishness of Jesus, Wipf & Stock Publishers (2003). ISBN 1-59244-313-3.

- ↑ Neusner, Jacob A Rabbi Talks With Jesus, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7735-2046-5. Rabbi Neusner contends that Jesus' teachings were closer to the House of Shammai than the House of Hillel.

- ↑ Based on a comparison of the Gospels with the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially the Teacher of Righteousness and Pierced Messiah. Eisenman, Robert James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Penguin (Non-Classics), 1998. ISBN 0-14-025773-X; Stegemann, Hartmut The Library of Qumran: On the Essenes, Qumran, John the Baptist, and Jesus. Grand Rapids MI, 1998. See also Broshi, Magen, "What Jesus Learned from the Essenes," Biblical Archaeology Review, 30:1, pg. 32-37, 64. Magen notes similarities between Jesus' teachings on the virtue of poverty and divorce, and Essene teachings as related in Josephus' The Jewish Wars and in the Damascus Document of the Dead Sea Scrolls, repspectively.

- ↑ The Gospel accounts show both John the Baptist and Jesus teaching repentance and the coming Kingdom of God. Some scholars have argued that Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet; see Schwietzer, Albert The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, pgs. 370–371, 402. Scribner (1968), ISBN 0-02-089240-3; Ehrman, Bart Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press USA, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512474-X. Crossan, however, makes a distinction between John's apocalyptic ministry and Jesus' ethical ministry. See Crossan, John Dominic, The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus, pgs. 305-344. Harper Collins, 1998. ISBN 0-06-061659-8.

- ↑ This includes the belief that Jesus was the Messiah. Brown, Michael L. Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus: Messianic Prophecy Objections Baker Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8010-6423-6. Brown shows how the Christian concept of Messiah relates to ideas current in late Second Temple period Judaism. See also Klausner, Joseph, The Messianic Idea in Israel: From its Beginning to the Completion of the Mishnah, Macmillan 1955; Patai, Raphael, Messiah Texts, Wayne State University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8143-1850-9; Crossan, John Dominic, The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus, pg. 461. Harper Collins, 1998. ISBN 0-06-061659-8. Patai and Klausner state that one interpretation of the prophecies reveal either two Messiahs, Messiah ben Yosef (the dying Messiah) and Messiah ben David (the Davidic King), or one Messiah who comes twice. Crossan cites the Essene teachings about the twin Messiahs. Compare to the Christian doctrine of the Second Coming.

- ↑ Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1944. p. 558; John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew. New York: Doubleday, 1991 vol. 1:205-7;

- ↑ Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities, Oxford, 2003, p. 102.

- ↑ Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities, Oxford, 2003, p. 124-125.

- ↑ Wace, Henry, Commentary on Marcion

- ↑ Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities, Oxford, 2003, p. 103, p. 104-105, p.108

- ↑ John 1:1; 8:58; 10:30

- ↑ http://www.peterkreeft.com/topics/christ-divinity.htm

- ↑ Western Christianity, following Augustine of Hippo, generally affirms that humanity inherited both the tendency to sin and the guilt of Adam and Eve's sin. The doctrine in Eastern Christianity is that humanity inherited the tendency to sin, but not the guilt for Adam and Eve's sin. This doctrine, also adopted by some in the Western Church as a form of Arminianism, is sometimes called semipelagianism. A minority of Christians affirm Pelagianism, which states that neither the condition nor the guilt of original sin is inherited; rather, we all freely face the same choice between sin and salvation that Adam and Eve did. Pelagianism was opposed by the Council of Carthage in 418 AD/CE.

- ↑ John 14:28;

- ↑ "Jesus The Ruler "Whose Origin Is From Early Times", The Watchtower, June 15, 1998, p. 22.

- ↑ Based on Galatians 3:13 and Acts 5:30. [http://www.watchtower.org/library/jt/article_03.htm Jehovah's Witnesses Official Web Site ], accessed June 8, 2006.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Sheikh Ahmad Kuftaro, "What is Islam? Jesus", Kuftaro.org, accessed March 15, 2006.

- ↑ III&E, "Prophethood in Islam", Accessed March 19, 2006

- ↑ "The Islamic and Christian views of Jesus: a comparison", ISoundvision, accessed March 15, 2006.

- ↑ Abdullah Ibrahim, "The History of the Quran and the Injil", Arabic Bible Outreach Ministry, accessed March 15, 2006.

- ↑ Mufti A.H. Elias, "Jesus (Isa) A.S. in Islam, and his Second Coming", Islam.tc, accessed March 15,2006.

- ↑ Mufti A.H. Elias, "Jesus (Isa) A.S. in Islam, and his Second Coming", Islam.tc Network, accessed May 10, 2006.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parrinder, Jesus in the Quran, p.187, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1996, ISBN 1-85168-094-2.[1]

- ↑ Javed Ahmed Ghamidi, Qur'anic Verse regarding Second Coming of Jesus.[2]

- ↑ The Second Coming of Jesus, Renaissance - Monthly Islamic Journal, Vol. 14, No. 9, September, 2004.[3]

- ↑ M. M. Ahmad, "The Lost Tribes of Israel: The Travels of Jesus", Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Accessed March 16, 2006.

- ↑ Günter Grönbold, Jesus In Indien, München: Kösel 1985, ISBN 3-466-2070-1. Norbert Klatt, Lebte Jesus in Indien?, Göttingen: Wallstein 1988.

- ↑ Rabbi Shraga Simmons, "Why Jews Don't Believe in Jesus", accessed March 14, 2006; "Why Jews Don't Believe in Jesus", Ohr Samayach - Ask the Rabbi, accessed March 14, 2006; "Why don't Jews believe that Jesus was the messiah?", AskMoses.com, accessed March 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Hilchot Malachim (laws concerning kings) (Hebrew)", MechonMamre.org, accessed March 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Question 18.3.4: Reform's Position On...What is unacceptable practice?", faqs.org, accessed March 14, 2006.

- ↑ Rabbi Ephraim Buchwald, "Parashat Re'eh 5764-2004: Identifying a True Prophet", National Jewish Outreach Program, accessed March 14, 2006; Tracey Rich, "Prophets and Prophecy", Judaism 101, accessed March 14, 2006; Rabbi Pinchas Frankel, "Covenant of History: A Fools Prophecy", Orthodox Union of Jewish Congregations of America, accessed March 14, 2006;Laurence Edwards, "Torat Hayim - Living Torah: No Rest(s) for the Wicked", Union of American Hebrew Congregations, accessed March 14, 2006.

See also

Template:Col-2- General Topics

- YHWH

- God

- Alaha

- Prayer

- Christianity

- Anno Domini and Common Era (which show how Jesus' birth has influenced the modern day calendar)

- INRI

- Nazarene

- The Bible

- List of books about Jesus

- Jesus and History

- Environment of Jesus

- New Testament Jesus

- Views on Jesus

- Religious perspectives on Jesus

- Islamic view of Jesus

- Pauline Christianity

- Apocrypha and Folk Christianity include many stories about Jesus besides those in the Bible.

- Jesus Christ in popular culture

- Related topics

References

- Allison, Dale. Jesus of Nazareth: Millenarian Prophet. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1999. ISBN 0-8006-3144-7

- Brown, Raymond E.. An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Doubleday, 1997. ISBN 0-385-24767-2

- Cohen, Shaye J.D. From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1988. ISBN 0-664-25017-3

- Cohen, Shaye J.D. The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. ISBN 0-520-22693-3

- Crossan, John Dominic. The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993. ISBN 0-06-061629-6

- Guy Davenport and Benjamin Urrutia. The Logia of Yeshua ; The Sayings of Jesus. Washington, DC: 1996. ISBN 1-887178-70-8

- De La Potterie, Ignace. "The Hour of Jesus." New York: Alba House, 1989.

- Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1944. ISBN 0-671-11500-6

- Ehrman, Bart. The Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-514183-0

- Ehrman, Bart. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-515462-2

- Fredriksen, Paula. Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity. New York: Vintage, 2000. ISBN 0-679-76746-0

- Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-300-04864-5

- Finegan, Jack. Handbook of Biblical Chronology, revised ed. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1998. ISBN 1-56563-143-9.

- Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, New York: Anchor Doubleday,

- v. 1, The Roots of the Problem and the Person, 1991. ISBN 0-385-26425-9

- v. 2, Mentor, Message, and Miracles, 1994. ISBN 0-385-46992-6

- v. 3, Companions and Competitors, 2001. ISBN 0-385-46993-4

- O'Collins, Gerald. Interpreting Jesus. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1983.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Jesus Through the Centuries: His Place in the History of Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-300-07987-7

- Robinson, John A. T. Redating the New Testament. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2001 (original 1977). ISBN 1-57910-527-0.

- Sanders, E.P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. New York: Penguin, 1996. ISBN 0-14-014499-4

- Sanders, E.P. Jesus and Judaism. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8006-2061-5

- Vermes, Geza. Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1981. ISBN 0-8006-1443-7

- Vermes, Geza. The Religion of Jesus the Jew. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1993. ISBN 0-8006-2797-0

- Vermes, Geza. Jesus in his Jewish Context. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2003. ISBN 0-8006-3623-6

- Wilson, A.N. Jesus. London: Pimlico, 2003. ISBN 0-7126-0697-1

- Wright, N.T. Jesus and the Victory of God. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1997. ISBN 0-8006-2682-6

- Wright, N.T. The Resurrection of the Son of God: Christian Origins and the Question of God. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2003. ISBN 0-8006-2679-6

External links

Template:Col-2- About-Jesus.org (Christian)

- Jesus Christ at WikiChristian

- Complete Sayings of Jesus Christ In Parallel Latin & English -- The Complete Christ Sayings

- Jesus Christ Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Latter-day Saint statement on the divinity of Jesus Christ

- An Hindu perspective on Jesus

- An Islamic perspective on Jesus

- The Historic & Reformation View of Jesus Christ: Solus Christus, Sola Gratia, Sola Fide, Sola Scriptura, Soli Deo Gloria

- Jesus Christ - Smith's Bible Dictionary article

- Overview of the Life of Jesus A summary of New Testament accounts.

- From Jesus to Christ — A Frontline documentary on Jesus and early Christianity.

- The Jewish Roman World of Jesus

- The Jesus Puzzle - Earl Doherty's website.

- Skeptic's Guide to Jesus