Free will

Free will refers to that feeling, or experience, one has that one can have complete control to choose among alternative actions, even in the face of psychological and other conflicting influences.[1] It is an age-old concern to separate what we can do something about from what we cannot. Much of human experience is interpreted on as depending upon our choices. Capturing the content of this subjective formulation, free will also is a philosophical position that human beings are able to choose between different courses of action in any given circumstance,[2] whereas the opposite position, determinism, claims that all our mental states and actions are made necessary by preceding causes, and the idea that we are free at all is an illusion.

These diametric extremes, on the one hand we always are in complete control, and on the other that we never are in control, unnecessarily restrict our options, an example of false dichotomy,[3] referred to specifically in this instance as naïve dualism.[4] Reality lies somewhere else, as it is abundantly clear that our actions can be dictated by factors outside our control and outside our awareness,[5] but it is unclear that such factors are decisive in every instance or in the long run. The present situation is that the ability to exercise free will is known definitely to be limited by many factors, sometimes strongly limited. However, a useful discussion of free will may require vocabulary and concepts not yet developed, and whatever its ultimate formulation, to rule free will out entirely requires an extrapolation of the present understanding of the brain beyond what is verifiable today, .

The controllable and uncontrollable aspects of decision making are logically separable using the following device:

|

|

The connection between will and action thereby is separated for further discussion. In particular, is there in nature anything that actually inhabits the domain of "will" so-defined, a domain beyond the reach of "external constraints"? A related distinction is that between brain and mind, with brain the physical matter where mental processes take place, and mind somehow (unclearly) related to consciousness and will. |

All of us have subjectively experienced being torn between doing one thing or another –what we would like to do, what we think we should do, or what we think others would appreciate our doing, and so on. We might assume that the decision is up to us, that we are free to do one thing or another, and others may heap blame or praise on us assuming the same thing. This assumption is what is meant by free will –the belief that whatever we may have done in actual fact, could have been otherwise because we might have decided on another course of action, and that before taking the action we were free to choose between alternatives. The claim might be: "Consciousness has the ability to override its genetic (and other) instructions and to set its own independent course of action."[7]

At the same time, we realize that some aspects of the world work in ways that can be understood because there are law-like processes that can be deciphered, and that allow us to predict some future events based upon observations of past events. The principle operating here is that future events are governed by physical laws rooted in past events, and the notion that this kind of explanation applies to everything that happens is known as determinism. Some have argued that the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics opens a door to a randomness in human behavior, which is foreign to human experience. Inasmuch as random atomic events are not under our control any more than predetermined events, determinism can be rewritten to include this randomness, for example, as follows: All our decisions are either implied by past events, or by random events, that in both cases do not involve us as agents, but which we simply witness.[8]

If the world is deterministic, our feeling that we are free to choose an action is simply an illusion. We have trouble believing all our actions are beyond our control, and that our sense of freedom is totally illusory, but we also have problems thinking that our actions are totally within our control. Although it is an exaggeration (at least at the moment) to think that science requires determinism,[9] it is apparent that "consciousness plays a far smaller role in human life than Western culture has tended to believe."[10]

This dilemma is what in philosophy is known as the problem of free will (or sometimes referred to by its flip-side as the dilemma of determinism), and it is a dilemma because it is difficult to decide how to assign responsibility for our actions. In a more nuanced formulation, the dilemma stems from the question posed as follows:

|

"Are behaviors, judgments, and other higher mental processes the product of free conscious choices, as influenced by internal psychological states (motives, preferences, etc.), or are those higher mental processes determined by those states?" John A. Bargh, Free Will is Un-natural[11] |

A clear statement of the dilemma is as follows:

|

"The idea of free will, though now rather in disfavor, expressed the popular and philosophical view that behavior reflects the outcome of a struggle between an autonomous, relatively virtuous, possibly spiritual self and the baser forces of external demand and inner cravings. The assumption that two different processes battle it out to determine action has been fundamental in theological views, such as beliefs about the judgment of individual souls based upon whether they choose virtuous or sinful acts. Likewise, it is central to some modern legal judgments that assign punishment not just on the basis of the action and its (criminal) consequences but also on the supposed state of mind of the perpetrator – reserving lesser punishment for crimes committed in mental states...that supposedly reduce the capacity of the nobler part of the self to restrain the wickeder impulses..." Roy F Baumeister et al., Free Willpower: A limited resource theory of volition, choice and self-regulation[12] |

Mind-body problem

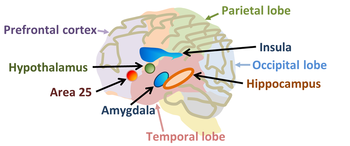

Some human brain areas involved in mental disorders. Area 25 refers to Brodmann's area 25, a region implicated in long-term depression.[13]

The idea of free will is one aspect of the mind-body problem, that is, consideration of the relation between mind (for example, consciousness, memory and judgment) and body (for example, the human brain and nervous system). In the context of free will, does the relation between mind and body allow for the mind to 'cause' neurological states, or is the mind simply an artifact or correlate of what the brain and nervous system are doing on their own? That question is presented as though the issue is empirical, but there are serious questions as to whether it is properly phrased that way, and whether standard methods separating the observed from the observer really apply to this investigation. Are there causal connections behind known correlations between subjective mental activity and objectively identified neurological events? Is the language of 'cause' and 'effect' too limited to describe huge systems of sensors with complex feedback arrangements? The discussion of free will falls into various parts: some empirical (What is going on in the brain?), some semantic (What are the possible meanings of free will, and are new concepts necessary?), some theoretical (there are many of these, among them: Does the disturbance of what is observed by the very act of observation imply that terms like free will and the terms used in neuroscience are fundamentally incompatible descriptions, making psychology irreducible to neuroscience?).

For example, interactionalist dualism suggests that some physical events cause some mental acts and some mental acts cause some physical events. Dualism allows humans free will, because mind only is correlated with brain activity, and is not reducible to it.[14] A modern dualist position from the field of artificial intelligence, or AI, is made by so called strong AI theorists, who say that the mind is separate from the brain in the same way that a computer algorithm exists independent of its many possible realizations in coding and physical implementation, and the brain and its 'wiring' is analogous to a computer and its software.[15] (Perhaps it is worth pointing out that the brain and its operation is known to be quite different from any man-made computer.[16]) Another version is the "three world" formulation of Popper.[17] These are examples of what is called epistemological pluralism, that is the notion that the mind-body problem is not reducible to the concepts of the natural sciences.

One contrasting approach is called cognitive naturalism, in which mind is simply part of nature, perhaps merely a feature of most very complex self-programming feedback systems, and must be studied by the methods of empirical science.[14] Certainly, some areas of the brain (see image) are connected to aspects of mental function and consciousness.

Attempts are being made to soften the boundary between these two views based upon self-organizing systems, exploring the conjecture that such systems can have a causal power over the organization of their deterministic subsystems, expressed in the ways these substratum elements are organized and put into action.[18]

|

“What must be explained is how a self-organizing or dynamical system can have a causal power over its own substrata, which is not reducible to the sum of the actions of the substrata, while at the same time causal closure is not violated at the substratum level.[...] any such causal analysis must use a theory of self-organization as their starting point, since only a dynamical system promises [...] the power to appropriate substratum elements into its own basins of attraction, rather than letting those basins be merely a higher-level description of the independent actions of the substrata.” R. D. Ellis Part III. The mind-body problem[18], p.49. |

One aspect of this development is the answer to the question: Is a machine realizable for which the goals of the machine are not imposed from the outside, but produced by the machine itself?[19]

An outstanding unsolved issue in the mind-body problem often is called the hard problem of consciousness, how physical phenomena acquire subjective characteristics becoming, for example, colors and tastes.[20] For example, "it is possible to know all the physical and functional facts concerning the operation of human brains without, for example, knowing what it is like subjectively to experience vertigo."[21] The subjective intuition of free will may fall into this category as well.

Philosophical positions

Using T, F for "true" and "false" and ? for undecided, there are exactly nine positions regarding determinism/free will that consist of any two of these three possibilities:[22]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinism D | T | F | T | F | T | F | ? | ? | ? |

| Free will FW | F | T | T | F | ? | ? | F | T | ? |

Incompatibilism may occupy any of the nine positions except (5), (8) or (3), which last corresponds to soft determinism. Position (1) is hard determinism,and position (2) is libertarianism. The position (1) of hard determinism adds to the table the contention that D implies FW is untrue, and the position (2) of libertarianism adds the contention that FW implies D is untrue. Position (9) may be called hard incompatibilism if one interprets ? as meaning both concepts are of dubious value. Compatibilism itself may occupy any of the nine positions, that is, there is no logical contradiction between determinism and free will, and either or both may be true or false in principle. Below some of these positions are examined in more detail.[22]

Incompatibilism

|

“Experience teaches us no less clearly than reason, that men believe themselves to be free, simply because they are conscious of their actions, and unconscious of the causes whereby those actions are determined.” B de Spinoza Ethics[23] |

One approach, of course, is simply to accept as a fact that human beings are not free, a position termed hard determinism or incompatibilism.[8] To accept this position is to accept that our actions are caused by things other than our will –that actions do not originate in volition (willing), but rather in forces that determine its disposition in one way or another, a view often associated with stoicism.[24] Hard determinism, however, insofar as it accepts a causal chain of events, means our present actions are determined in the past, and some consider that view to wholly destroy any notion of moral responsibility. From this stance, freedom is considered a necessary component of responsibility, for why should anyone be blamed or praised for actions that could not have been otherwise?

Stoics, however, considered that an agent was responsible for thinking through their choices, even though the appearance of choice is illusory.[24] This curious situation led to much debate over the centuries, with Chrysippus (279 – 206 BC) attempting a way out of this apparent contradiction by separating external antecedant causes from the internal disposition receiving this cause, a solution adopted by many thinkers since that time in various formulations.[25]

Libertarianism

Others have argued that determinism is false, or that at the very least, human actions are a special case and stand outside the requirements of a deterministic universe.[8] In simple terms, freedom of thought is distinguished from freedom of action, and their connection is made a subject of study. By separating the rules of thought, one might be free to choose between alternatives, one might have causal powers.

Saint Augustine held this view, the capacity for metaphysical freedom.[26] Kant also subscribed to this view: besides nature and empirical knowledge, there is the realm of things in themselves accessible to thought and governed by different rules; a distinction between phenomena and noumena.[27]

In a kind of inverse form of Kant's approach, Pierre Duhem suggested that scientific theory was simply a device to facilitate economy of thought, and could not be considered to encompass "reality".[28] Thus, thought is a distillation of reality, and what goes on "in reality" is a much deeper and broader question than how we describe it. Similar to consciousness itself, scientific theory is a synopsis of some of what goes on, not the full text. This view of science as dealing with only part of the picture opens the way to more modern statements of the separation of causality in nature from that in the mind.

For example, we have this modern statement of the claim:

|

"The nonconcious forms of self-regulation may follow different causal principles and do not rely on the same resources as the conscious and effortful ones." Roy F Baumeister et al., Free Willpower: A limited resource theory of volition, choice and self-regulation[12] |

A different approach questions the concept of "causality" itself, considering it a construct inappropriate to the description of human and animal behavior. See the section below on causality.

Compatibilism

An intermediate view has been to soften the requirements of what it means to be free. One accepts the fact that actions have causes, but argues that this does not mean we are not free.[8]

In the approach known as soft determinism, I am still free even though my character, common sense and so forth, strongly support a course of action, because they do not compel me to act in this way, nor preclude alternatives. Of course freedom understood in this way is not an arbitrary freedom. It is freedom in the sense that nothing stops me from doing otherwise, even though it is unlikely. Put in an extreme form: "A puppet is free as long as he loves his strings".[5]

What are the "strings" attached to our decisions? The questions of character, predisposition, programming and so on, are part of the field of behaviorism, where behavior modification, reinforcement, and so forth are studied.[29] A closely related field is cognitive psychology, the psychology of cognition, studying matters such as the processes involved in memorization and decision making.[30][31]

Complementarity

In quantum mechanics the notion of complementarity arises, that is, different aspects of a description that are mutually exclusive. Bohr (1922 winner of the Nobel Prize in physics) suggested complementarity is useful outside of quantum theory. In asking whether one can perform an action, one is both observer and subject, which is posited to be an untenable situation: one must adopt one or the other stance.[32][33] To quote Niels Bohr:[34]

|

"For instance, it is impossible, from our standpoint, to attach an unambiguous meaning to the view sometimes expressed that the probability of the occurrence of certain atomic processes in the body might be under the direct influence of the will. In fact, according to the generalized interpretation of the psycho-physical parallelism, the freedom of the will is to be considered as a feature of conscious life which corresponds to functions of the organism that not only evade a causal mechanical description but resist even a physical analysis carried to the extent required for an unambiguous application of the statistical laws of atomic mechanics. Without entering into metaphysical speculations, I may perhaps add that an analysis of the very concept of explanation would, naturally, begin and end with a renunciation as to explaining our own conscious activity."... |

| "...On the contrary, the recognition of the limitation of mechanical concepts in atomic physics would rather seem suited to conciliate the apparently contrasting viewpoints of physiology and psychology. Indeed, the necessity of considering the interaction between the measuring instruments and the object under investigation in atomic mechanics exhibits a close analogy to the peculiar difficulties in psychological analysis arising from the fact that the mental content is invariably altered when the attention is concentrated on any special feature of it." |

These observations are echoed by experimentalists studying brain function:[35]

|

"...it is important to be clear about exactly what experience one wants one's subjects to introspect. Of course, explaining to subjects exactly what the experimenter wants them to experience can bring its own problems–...instructions to attend to a particular internally generated experience can easily alter both the timing and he content of that experience and even whether or not it is consciously experienced at all." Susan Pockett, The neuroscience of movement[35] |

Another description of this issue is by Northoff:[36]

|

"Epistemically, the mind is determined by mental states, which are accessible in First-Person Perspective. In contrast, the brain, as characterized by neuronal states, can be accessed in Third-Person Perspective. The Third-Person Perspective focuses on other persons and thus on the neuronal states of others' brain while excluding the own brain. In contrast, the First-Person Perspective could potentially provide epistemic access to own brain...However, the First-Person Perspective provides access only to the own mental states but not to the own brain and its neuronal states." Georg Northoff, Philosophy of the Brain: The Brain Problem, p. 5[36] |

These observations suggest the possibility that "free will" and neurology inhabit different realms, and it is confusion to try to explain "free will" using a neurological approach that by its very nature excludes the effects of observation upon what is observed. In broad terms, this argument complements that of Chrysippus (279 – 206 BC).[25]

Causality

In extending the application of the principle of complementarity, Bohr questioned the everyday ideas of causality:

|

"...any observation necessitates an interference with the course of the phenomena, which is of such a nature that it deprives us of the foundation underlying the causal mode of description." Neils Bohr: The Atomic Theory and the Fundamental Principles underlying the Description of Nature[37] |

Bohr considered these reservations might apply in trying to explain the connection between mental and physical events in terms of observation altering what is observed. If our notion of causality is questioned, "free will" as mental causation takes on a different interpretation.

Similar reservations have been expressed by others, but take a broader, more historical approach. Historically, two types of causality (the "being responsible for something else") are distinguished, with several sub-genres.[38] The first kind of causes is that which is included in the effect and is part of it (embedment); the arising of something out of itself. The second kind of causes does not reside in the effect and is separate from it.

In the first category, two subdivisions arise:

- causa materialis or material cause: the implied but not yet realized result, as Michelangelo said his act of sculpture "released" the form already present and buried within the marble.[39]

- causa formalis or formal causality: a mental construct created to relate an effect to a cause.

The second category of external causes also divides into two:

- causa efficiencs or efficient causality: cause and effect can be separated and determined, the usual 'cause' of science as stimulus and response.

- causa finalis or final causality: the objective as shaping the action; as may entail its expression though no cause as yet exists. Thus, the desire for a king may cause a coronation, and goals set by evolution may determine a response.

These notions of cause may not be all that distinct. For example, the "principle of least action", and its extension to the Feynman path integral, predicts the realized path of a system as a minimization of 'action' over all possible paths, seemingly suggesting that the system 'action' (a causa materialis) already embodies the path to be taken given the objective of 'least action' (a causa finalis). And yet this formulation is equivalent to those based upon Newton's laws or quantum mechanics, which invoke only causa efficiencs, and it has been argued that physics theories themselves constitute a causa formalis, no more than a mental shorthand to link selected events, a subset of all events.[28]

Northoff regards the restriction of cause to causa efficiencs precludes a proper understanding of the dynamics and self-organization of the brain, restricting explanations to an 'outside of the brain' point of view: “the possibility of mental causation is necessarily dependent on the possibility of 'final and formal causality'”.[40]

Along these lines, Freeman introduces the replacement of "causality" by what he calls "circular causality" to "allow for the contribution of self-organizing dynamics", the "formation of macroscopic population dynamics that shapes the patterns of activity of the contributing individuals", applicable to "interactions between neurons and neural masses...and between the behaving animal and its environment":

|

"Circular causality departs so strongly from the classical tenets of necessity, invariance, and precise temporal order that the only reason to call it that is to satisfy the human habitual need for causes....The very strong appeal of agency to explain events may come from the subjective experience of cause and effect that develops early in human life, before the acquisition of language...the question I raise here is whether brains share this property with other material objects in the world. " (Walter J. Freeman, Consciousness, intentionality and causality[41]) |

Freeman's usage for the term circular causality appears akin to the views of Kelso,[42] and is more radical than the common use of this term, which refers to causality in a system with feedback.[43] A more specific use of this term is as follows:

|

"Note we are dealing here with circular causality. On the one hand the order parameter enslaves the atoms, but on the other hand it is itself generated by the joint action of the atoms" (Hermann Haken, Information and Self-Organization: A Macroscopic Approach to Complex Systems[44]) |

Self-programming robots

Today robots can be made that adapt their responses to their environment through self-programming, so-called intelligent robots. Much of the description of these machines seems parallel to human behavior, although technology has still not reached sufficient complexity to make a strong case for the similarities.[45]

| "Some people think that consciousness can arise only in organic, of flesh-and-blood beings. Others speculate that self-awareness might develop in any sufficiently complex network that is set up to operate like a brain...Could a conscious robot – a being created by humans and not by God – ever be said to have a soul? "[46] |

Is such a machine deterministic? We cannot predict the machine's exact behavior without a complete knowledge of its personal history with its environment, the reliability of its components, and its present state of programming, uncertainties in which limit us to probabilistic statements. It may be that this question is objectively undecidable, and has only an answer according to some or another theoretical formulation, in particular, a statistical answer indicating a probable range of responses to a probable range of inputs.

Groups of cooperating robots also are envisioned:

| "The interaction of multiple behavioral robots can be regarded as a continuum between two diverse types of behavior. At one extreme, the behavior can regarded as being egoistic, where a robot is concerned purely with self directed behavior, e.g. energy conservation. At the other extreme their behavior can be regarded as being altruistic, e.g. when a group of robots need to work together to perform some common task."[47] |

One can conjecture that some such groups could evolve following a Darwinian scheme, not only an interest of engineers,[48] but a recurrent topic of science fiction.[49]

| "The marvels accomplished by evolution inspired many researchers with the long term goal of automatically designing and even manufacturing complete robotics "lifeforms" with as little human intervention as possible." (Doncieux et al., §1.4.4 p. 12[48]) |

Implementation of decisions

Addiction

The separation of freedom of action from freedom of will is demonstrated in addiction. An addict has disconnected their will that identifies a course of action as desirable from their ability to enforce that action.[50] Brain imaging of addicts and non-addicts show differences in brain activity and can relate the process of addiction to a reprogramming of the brain's handling of dopamine that can be reversed only with a very prolonged and multipronged therapy.[51]

| "Most PET (Positron Emission Tomography) studies of drug addiction have concentrated on the brain dopamine (DA) system, since this is considered to be the neurotransmitter system through which most drugs of abuse exert their reinforcing effects. A reinforcer is operationally defined as an event that increases the probability of a subsequent response, and drugs of abuse are considered to be much stronger reinforcers than natural reinforcers (e.g. sex and food). The brain DA system also regulates motivation and drive for everyday activities. These imaging studies have revealed that acute and chronic drug consumption have different effects on proteins involved involved in DA synaptic transmission. ... chronic drug consumption results in marked decrease in DA activity which persists months after detoxification and which is associated with deregulation of frontal brain regions. " (Volkow et al.[52]) |

| "One of the most consistent findings from imaging studies is that of abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex... The prefrontal cortex is involved in decision making and in inhibitory control... Thus its disruption could lead to inadequate decisions that favor immediate rewards over delayed but more favorable responses. It could also account for the impaired control over the intake of the drug even when the addicted subject expresses the desire to refrain from taking the drug. " (Volkow et al.[52]) |

Response times

Studies of the timing between actions and the conscious decision to act have a bearing upon free will. A subject's declaration of intention to move a finger appears after the brain has begun to implement the action, suggesting to some that unconsciously the brain has made the decision before the conscious mental act to do so. Some believe the implication is that free will was not involved in the decision and is an illusion. The first of these experiments reported the brain registered activity related to the move about 0.2 s before movement onset.[53] However, these authors also found that awareness of action was anticipatory to activity in the muscle underlying the movement; the entire process resulting in action involves more steps than just the onset of brain activity.[54][55]

Some argue that placing the question of free will in the context of motor control is too narrow. The objection is that the time scales involved in motor control are very short, and motor control involves a great deal of unconscious action, with much physical movement entirely unconscious and not a matter of intention at all. On that basis "...free will cannot be squeezed into time frames of 150-350 ms; free will is a longer term phenomenon" and free will is a higher level activity that "cannot be captured in a description of neural activity or of muscle activation..." [56]

The bearing of timing results upon notions of free will appears complex, and remains a topic of discussion.

Emotion

From the perspective of evolutionary psychology, emotions evolved in humans in response to environmental challenges, and serve to organize human responses according to success in handling ancestral experience:[57]

|

"an emotion is a superordinate program whose function is to direct the activities and interactions of many subprograms, including those governing perception, ...categorization and conceptual frameworks,...communication processes, and the recalibration of probability estimates, situation assessments... ." "All cognitive programs [...] are sometimes mistaken for homunculi,[58] that is, entities endowed with free will. A homunculus scans the environment and freely chooses successful actions. ... It is the task of cognitive psychologists to replace theories that implicitly posit such an impossible entity with theories that can be implemented as fixed programs with open parameters." "Just as a computer can have an hierarchy of programs, some of which control the activation of others, the human mind can as well. Far from being internal free agents, these programs have an unchanging structure regardless of the needs of the individual or his or here circumstances because they were designed to create states that worked well in ancestral situations, regardless of their consequences in the present." John Tooby and Leda Cosmides: Conceptual foundations of evolutionary psychology[57] |

Other than undefined "open parameters", perhaps related to "recalibrations", these words leave little room for the effects found in behavioral psychology, cognitive psychology, and the field of developmental psychology associated with the names of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, which find much room for environmental factors arising during the development of each individual.[59] The field of evolutionary psychology is marked by some heated controversy.

Although evolutionary psychologists attempt to understand the organization of the mind and brain based upon how they arose, it is hampered by the observation that different species arose in different environments with different responses, making cross-species comparisons very difficult.[60]

Epigenetics

"Once nurture seemed clearly distinct from nature. Now it appears that our diets and lifestyles can change the expression of our genes. How? By influencing a network of chemical switches within our cells collectively known as the epigenome."[61] Various mechanisms for transference of such environmental response to the next generation are under study.[62][63] In the context of free will, these mechanisms indicate pathways at a very basic level that can change the programming even of identical twins, and even that of successive generations. Not free will, but certainly adaptivity and originality of response in populations.

Summary

The various notions of free will conflict, but involve many of the same elements. These matters have been argued for millenia, and their resolution may depend upon developing a better understanding of what actually goes on in the brain.[41]

| "Although strong advances are being made in analyzing the dynamics of the limbic system and its centerpieces, the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus, their self-organized spatial patterns, their precise intentional contents, and their mechanisms of formation in relation to intentional action are still unknown." (Walter J. Freeman, Consciousness, intentionality and causality[41]) |

In popular accounts of this subject, the same modern developments are used as new wine in old bottles. On one hand, we have K. E. Stanovitch's The Robot's Rebellion: Finding Meaning in the Age of Darwin, which advances the view that decisions are possible using "instrumental rationality" with goals "keyed to the life interest of the vehicle" to replace "gut" decisions.[64] On the other hand we have books like Sam Harris' Free Will,[5] and D.M. Wagener's The Illusion of Conscious Will,[65] that take the view that consciousness is completely illusory, and old-fashioned determinism is completely correct.

At an individual level, perhaps we can be viewed as complex machines with built-in goals sought using algorithms for survival, which adapt to experience. The conscious monitoring of some aspects of this reprogramming may generate feelings of mental control over our individual destinies even though these feelings may be illusory. Our survival depends upon the execution of ancestral programming that includes some adaptivity, and our mental states may be analogous to a debugger watching the evolution of some code.

The occurrence of mutations introduces a random aspect. Unusual circumstances occur due to random events, provoking new responses. New types of individual arise that exhibit novel reactions even to mundane environmental factors. These novelties may permit (or even force) individuals and societies to explore new avenues. Although once a new path is initiated, evolutionary programming and natural law exert their influences, events proceed with a complexity that defies prediction.

References

- ↑ "One of the strongest supports for the free choice thesis is the unmistakable intuition of virtually every human being that he is free to make the choices he does and that the deliberations leading to those choices are also free flowing." Corliss Lamont as quoted by Gregg D Caruso (2012). Free Will and Consciousness: A Determinist Account of the Illusion of Free Will. Lexington Books, p. 8. ISBN 0739171364.

- ↑ Historically, "free will" has had a number of definitions, some tied to religious notions of being able to choose between "right" and "wrong". The definition here is that described as the "common notion" by evangelical thinker Gordon H. Clark (1961). Religion, reason, and revelation. Presbyterian and Reformed Pub. Co, pp. 202-203. “Free will has been defined as the ability under given circumstances, to choose either of two courses of action... Whatever motives or inclinations a man might have, or whatever inducements may be laid before him, that might seem to turn him in a given direction, he may at a moment disregard them all and do the opposite.”

- ↑ The offering of only a pair of contrary alternatives that do not exhaust the possibilities. See Sylvan Barnet, Hugo Bedau (2010). Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing: A Brief Guide to Argument, 7th ed. Macmillan, p. 376. ISBN 0312601603.

- ↑ The term naïve dualism is used by John Monterosso, Barry Schwartz (July 27, 2012). Did your brain make you do it?. Gray Matter. New York Times. Retrieved on 2012-07-29.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sam Harris (2012). Free Will. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 1451683405.

- ↑ O'Connor, Timothy (Oct 29, 2010). Edward N. Zalta, ed:Free Will. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition).

- ↑ A paraphrase of a statement by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row, p. 24. ISBN 0060920432.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Mark Balaguer (2009). “Introduction”, Free Will As an Open Scientific Problem. MIT Press, pp. 1 ff. ISBN 0262013541.

- ↑ The view of scientific determinism goes back to Laplace: "We ought to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its antecedent state". However, the necessary underlying assumption of complete knowledge by an observer, including exact knowledge of the observer themselves, is an extreme idealization that renders any such claim unverifiable. See John T Roberts (2006). “Determinism”, Sahotra Sarkar, Jessica Pfeifer, Justin Garson, eds: The Philosophy of Science: An Encyclopedia. N-Z, Indeks, Volume 1. Psychology Press, pp. 197 ff. ISBN 0415939275.

- ↑ Quote from Tor Nørretranders (1998). “Preface”, The user illusion: Cutting consciousness down to size, Jonathan Sydenham translation of Maerk verden 1991 ed. Penguin Books, p. ix. ISBN 00140230122.

- ↑ John A Bargh (2007-011-16). Free will is un-natural. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Roy F Baumeister, Matthew T Galliot, Dianne M Tice (2008). “Chapter 23: Free Willpower: A limited resource theory of volition, choice and self-regulation”, Ezequiel Morsella, John A. Bargh, Peter M. Gollwitzer: Oxford Handbook of Human Action, Volume 2 of Social Cognition and Social Neuroscience. Oxford University Press, pp. 487 ff. ISBN 0195309987.

- ↑ Sidney H Kennedy et al. (May 01, 2011). "Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: Follow-up after 3 to 6 years". The American Journal of Psychiatry 168 (5). Retrieved on 2012-09-04.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 See for example: Sandro Nannini (2004). “Chapter 5: Mental causation and intentionality in a mind naturalizing theory”, Alberto Peruzzi, ed: Mind and Causality. John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 69 ff. ISBN 1588114759.

- ↑ John R Searle (1997). John Haugeland, ed: Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, and Artificial Intelligence, 2nd ed. MIT Press, p. 203. ISBN 0262082594.

- ↑ For example, see the discussion in Steve M. Potter (2008). “What can AI get from neuroscience?”, Max Lungarella, Fumiya Iida, Josh Bongard, eds: 50 Years of Artificial Intelligence: Essays Dedicated to the 50th Anniversary of Artificial Intelligence. Springer, pp. 174 'ff. ISBN 3540772952.

- ↑ Karl Raimund Popper (1999). “Notes of a realist on the body-mind problem”, All Life is Problem Solving, A lecture given in Mannheim, 8 May, 1972. Psychology Press, pp. 23 ff. ISBN 0415174864. “The body-mind relationship...includes the problem of man's position in the physical world...'World 1'. The world of conscious human processes I shall call 'World 2', and the world of the objective creations of the human mind I shall call 'World 3'.”

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ralph D Ellis (2000). “Efferent brain processes and the enactive approach to consciousness”, Nicholas Humphrey, ed: How to Solve the Mind-- Body Problem, Reprint from Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7 (4)2000, pp. 40-50. Imprint Academic, pp. 48-49. ISBN 0907845088.

- ↑ Henri Atlan (2011). “Chapter 2: Intentional self-organization: Emergence and reduction, toward a physical theory of reduction”, Todd Meyers, Stefanos Geroulanos: Henri Atlan: Selected Writings, Translation of Thesis 11 52 (February 1998): 5-34. Fordham University Press, pp. 70 ff.

- ↑ For a brief historical rundown, see James W. Kalat (2008). Biological Psychology, 10th ed. Cengage Learning, p. 7. ISBN 0495603007.

- ↑ Barry Loewer. Edward Craig, general editor: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Volume 6. Oxford University Press, p. 310. ISBN 0415073103. referring to Nagel (What it's like to be a bat, 1974) and to Jackson (What Mary didn't know, 1986)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Galen Strawson (2010). Freedom and belief, Revised ed. Oxford University Press, p. 6. ISBN 0199247501.

- ↑ Benedict de Spinoza (2008). “Part III: On the origin and nature of the emotions; Postulates (Proposition II, Note)”, R. H. M. Elwes, trans: The Ethics, Original work published 1677. Digireads.com Publishing, p. 54. ISBN 1420931148.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Ricardo Salles (2005). The Stoics on Determinism and Compatibilism. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0754639762.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Keimpe Algra (1999). “Chapter VI: The Chyrsippean notion of fate: soft determinism”, The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, p. 529. ISBN 0521250285.

- ↑ Saint Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (1993). “Introduction by translator”, On Free Choice Of The Will, Translation by Thomas Williams of Augustine's work of AD 391-395. Hackett Publishing, p. 12. ISBN 0872201880.

- ↑ Allen W Wood (1998). Patricia Kitcher, ed: Kant's Critique of Pure Reason: Critical Essays. Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 240 ff. ISBN 0847689174.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem (1991). The Aim and Structure of Physical Theory. Princeton University Press, p. 21. ISBN 069102524X.

- ↑ BF Skinner (2011). About Behaviorism. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 0307797848.

- ↑ An historical outline of the evolution of cognitive psychology and its relation to behaviorism is found in E. Bruce Goldstein (2008). “Chapter 1: Introduction to Cognitive Psychology”, Cognitive Psychology: Connecting Mind, Research, and Everyday Experience, 2nd ed. Cengage Learning, pp. 1 ff. ISBN 0495095575.

- ↑ Robert J. Sternberg (2009). “Psychological antecedents of cognitive psychology”, Cognitive Psychology, 5th ed. Cengage Learning, pp. 5 ff. ISBN 049550629X.

- ↑ Andrew Whitaker (2006). Einstein, Bohr And the Quantum Dilemma: From Quantum Theory to Quantum Information, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, p. 191. ISBN 0521671027.

- ↑ For a discussion of a program to establish complementarity as speculated by Bohr, see Paul McEvoy (2001). Niels Bohr: Reflections on Subject and Object. MicroAnalytix, p. 323. ISBN 1930832001.

- ↑ Niels Bohr (April 1, 1933). "Light and Life". Nature: p. 457 ff. Full text on line at us.archive.org.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Susan Pockett (2009). “The neuroscience of movement”, Susan Pockett, WP Banks, Shaun Gallagher, eds: Does Consciousness Cause Behavior?. MIT Press, p. 19. ISBN 0262512572.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 A rather extended discussion is provided in Georg Northoff (2004). Philosophy of the Brain: The Brain Problem, Volume 52 of Advances in Consciousness Research. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 1588114171.

- ↑ Neils Bohr. The Atomic Theory and the Fundamental Principles underlying the Description of Nature; Based on a lecture to the Scandinavian Meeting of Natural Scientists and published in Danish in Fysisk Tidsskrift in 1929. First published in English in 1934 by Cambridge University Press.. The Information Philosopher, dedicated to the new information philosophy. Robert O. Doyle, publisher. Retrieved on 2012-09-14.

- ↑ Nader El-Bizri (2000). The Phenomenological Quest Between Avicenna and Heidegger. Global Academic Publishing, pp. 97-98. ISBN 1586840053.

- ↑

As translated with artistic license by Eric Scigliano:

- "The finest artist can't conceive a thought

- that the marble itself does not bind

- within its shell, waiting to be brought

- out by the hand that serves the artist's mind."

- ↑ Georg Northoff (2004). Philosophy of the Brain: The Brain Problem, Volume 52 of Advances in Consciousness Research. John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 137-139. ISBN 1588114171.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Walter J Freeman (2009). “Consciousness, intentionality and causality”, Susan Pockett, WP Banks, Shaun Gallagher, eds: Does Consciousness Cause Behavior?. MIT Press, p. 88. ISBN 0262512572.

- ↑ J. A. Scott Kelso (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior. MIT Press, p. 16. ISBN 0262611317. “An order parameter is created by the correlation between the parts, but in turn influences the behavior of the parts. This is what we mean by circular causality.” Kelso also says (p. 9): "But add a few more parts interlaced together and very quickly it becomes impossible to treat the system in terms of feedback circuits. In such complex systems, ... the concept of feedback is inadequate.[...] there is no reference state with which feedback can be compared and no place where comparison operations are performed."

- ↑ Namhee Lee, Lisa Mikesell, Anna Dina L. Joaquin, Andrea W. Mates, John H. Schumann (2009). “Feedback and circular causality”, The Interactional Instinct: The Evolution and Acquisition of Language. Oxford University Press, pp. 26 ff. ISBN 0195384237.

- ↑ Hermann Haken (2006). Information and Self-Organization: A Macroscopic Approach to Complex Systems, 3rd ed. Springer, p. 25. ISBN 3540330216.

- ↑ Drew McDermott (2007). “Chapter 6: Artificial intelligence and consciousness”, Philip David Zelazo, Morris Moscovitch, Evan Thompson, eds: The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press, pp. 117 ff. ISBN 0521857430.

- ↑ Rebecca Stefoff (2007). Robots. Marshall Cavendish, p. 118. ISBN 0761426019.

- ↑ Kerstin Dautenhahn (2000). Human Cognition and Social Agent Technology. John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 202. ISBN 9027251398.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 This field is sometimes called Darwinian engineering or evolutionary robotics. See for example, Stéphane Doncieux, Jean-Baptiste Mouret, Nicolas Bredechte, Vincent Padois (2011). “Chapter 1: Evolutionary robotics: exploring new horizons”, Stéphane Doncieux, ed: New Horizons in Evolutionary Robotics: Extended Contributions from the 2009 EvoDeRob Workshop. Springer, pp. 3 ff. ISBN 3642182712.

- ↑ Barbara Creed (2009). “Intelligent machines and created life forms”, Darwin's Screens: Evolutionary Aesthetics, Time and Sexual Display in the Cinema. Academic Monographs, pp. 65 ff. ISBN 0522857094.

- ↑ How can I tell if I have a drinking problem? One determinant is: "If you sometimes get drunk when you fully intend to stay sober." (2006) “Alcoholism: Questions and answers”, Johannes P. Schade, ed: The Complete Encyclopedia of Medicine & Health. Foreign Media Group, p. 134. ISBN 1601360010.

- ↑ One mechanism of addiction is the interruption of recycling of dopamine into a transmitting neuron by blocking of dopamine transporters, resulting in a build-up of dopamine in the synapse. See, for example, Katherine Van Wormer, Diane Rae Davis (2012). “Caption to Figure 3.4”, Addiction Treatment, 3rd ed. Cengage Learning, p. 154. ISBN 0840029160. For a discussion of therapy, see for example Carol Mattson Porth (2008). “Disorders of Abuse and Addiction”, Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States, 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p. 1316 ff. ISBN 1605473901. Link is to the Canadian edition.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Nora D Volkow, Joanna S Fowler, and Gene-Jack Wang (2007). “The addicted human brain: insights from imaging studies”, Andrew R Marks and Ushma S Neill, eds: Science In Medicine: The JCI Textbook Of Molecular Medicine. Jones & Bartlett Learning, pp. 1061 ff. ISBN 0763750832.

- ↑ Benjamin Libet et al. (1983). "Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential).". Brain 106: 623-642.

- ↑ Lars Strother, Sukhvinder Singh Obhi (2009). "The conscious experience of action and intention". Exp Brain Res 198: 535-539. DOI:10.1007/s00221-009-1946-7. Research Blogging.

- ↑ A brief discussion of possible interpretation of these results is found in David A. Rosenbaum (2009). Human Motor Control, 2nd ed. Academic Press, p. 86. ISBN 0123742269.

- ↑ Shaun Gallagher (2009). “Chapter 6: Where's the action? Epiphenomenalism and the problem of free will”, Susan Pockett, William P. Banks, Shaun Gallagher: Does Consciousness Cause Behavior?. MIT Press, 119-121. ISBN 0262512572.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 John Tooby, Leda Cosmides (2006). “Conceptual foundations of evolutionary psychology”, David M Buss, ed: The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 53-54. ISBN 0471264032.

- ↑ Note: A humunculus is a little person inside the head that carries out mental functions.

- ↑ Willis F Overton (2003). “Chapter 1: Development across the life span”, Lerner, M. Ann Easterbrooks, Jayanthi Mistry: Handbook of Psychology, Developmental Psychology, Volume 6 of Handbook of Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 13 ff. ISBN 0471264474.

- ↑ Irwin Silverman, Jean Choi (2006). “Locating places”, David M Buss, ed: The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, p. 180. ISBN 0471264032.

- ↑ Epigenetics. Nova Beta. Produced for PBS Online by WGBH Educational Foundation.

- ↑ Yongsheng Liu (September 2007). Like father like son. A fresh review of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. EMBO Reports. The European Molecular Biology Organization EMBO Rep. 2007 September; 8(9): 798-803. PMC1973965 DOI=10.1038/sj.embor.7401060

- ↑ Root Gorelick (2004). "Neo-Lamarckian medicine". Medical Hypotheses 62: pp. 299-303. DOI:10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00329-3. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Keith E. Stanovich (2005). The Robot's Rebellion: Finding Meaning in the Age of Darwin. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226771253. See in particular Chapter 8: Soul without mystery: Finding meaning in the age of Darwin, pp. 207 ff.

- ↑ Daniel M. Wegner (2003). The Illusion of Conscious Will. MIT Press. ISBN 0262731622.