Coal

Coal is a carbon-containing rock formed by the debris from the decay of ferns, vines, trees and other plants which flourished in swamps millions of years ago. Over time, the debris became buried and the actions of bacteria, heat and pressure transformed the debris first into peat (a precursor of coal) and then into the various types of coal as we know them today.[1][2][3] In more technical terminology, that process of transformation is referred to as metamorphosis, coalification or lithification.

Coal is extracted by mining from deposits that exist deep underground as well as deposits that are essentially at or near the surface of the ground. Because of the various degrees of transformation that occurred during the forming of coal deposits in different locations, the composition of coal varies from one deposit to another. No two coals are the same in every respect. In general, coal consists of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur and mineral matter (including compounds of silica, aluminum, iron, calcium, magnesium and others).

Coal classification

There are many compositional differences between the coals mined from the different coal deposits worldwide. The different types of coal are most usually classified by rank which depends upon the degree of transformation from the original source (i.e., decayed plants) and is therefore a measure of a coal's age. As the process of progressive transformation took place, the heating value and the fixed carbon content of the coal increased and the amount of volatile matter in the coal decreased. The method of ranking coals used in the United States and Canada was developed by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and is based on a number of parameters obtained by various prescribed tests:

- Heating value: The energy released as heat when coal (or any other substance) undergoes complete combustion with oxygen.

- Volatile matter: The portion of a coal sample which, when heated in the absence of air at prescribed conditions, is released as gases. It includes carbon dioxide, volatile organics and inorganic gases containing sulfur and nitrogen.

- Moisture: The water inherently contained within the coal and existing in the coal in its natural state of deposition. It as measured as the amount of water released when a coal sample is heated at prescribed conditions. It does not include any free water on the surface of the coal. Such free water is removed by air-drying the coal sample being tested.

- Ash: The inorganic residue remaining after a coal sample is completely burned and is largely composed of compounds of silica, aluminum, iron, calcium, magnesium and others. The ash may vary considerably from the mineral matter present in the coal (such as clay, quartz, pyrites and gypsum) before being burned.

- Fixed carbon: The remaining organic matter after the volatile matter and moisture have been released. It is typically calculated by subtracting from 100 the percentages of volatile matter, moisture and ash. It is composed primarily of carbon with lesser amounts of hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur.

The ASTM ranking system is presented in the table below:

Class or Rank |

Group |

Fixed Carbon (b) (wt % dry mmf) |

Volatile Matter (b) (wt % dry mmf) |

Gross Heating Value (c) (MJ/kg moist mmf) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal or greater than |

Less than |

Greater than |

Equal or less than |

Equal or greater than |

Less than | ||

| Anthracitic |

Metaanthracite (d) Anthracite (d) Semianthracite (d) |

98 92 86 |

98 92 |

2 8 |

2 8 14 |

||

| Bituminous |

Low-volatile bituminous (d) Medium-volatile bituminous (d) High-volatile A bituminous High-volatile B bituminous High-volatile C bituminous (e) High-volatile C bituminous (f) |

78 69 |

86 78 69 |

14 22 31 |

22 31 |

32.55 30.23 26.74 24.41 |

|

| Subbituminous |

Subbituminous A Subbituminous B Subbituminous C |

24.41 22.09 19.30 |

26.74 24.41 22.09 | ||||

| Lignite |

Lignite A Lignite B |

14.65 |

19.30 14.65 | ||||

| (a) This classification does not include a few coals (referred to as unbanded coals) having unusual physical and chemical properties falling within the fixed carbon and heating value ranges of the high-volatile bituminous and subbituminous ranks. (b) Percentage by weight on a dry and mineral matter free basis (mmf). | |||||||

The anthracitic coals, with the highest contents of fixed carbon and lowest contents of volatile material, have the highest rank. The lignite coals, with the lowest contents of fixed carbon and highest contents of volatile matter, have the lowest rank. The bituminous and subbituminous coals (in that order) are ranked between the anthracitic and lignite coal.

As a broad generality, the anthracitic coals have the highest heating value and the lignite coals have the lowest heating values.

There are other coal classification systems developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the United Kingdom and perhaps others.[5]

Coal assays

(Work on this section is in progress)

Coal reserves and production statistics

Economically recoverable coal deposits exist in more than 70 nations and in every major region of the world (Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America and South America). It has been estimated that the worldwide proven reserves of coal amounted to about 848 gigatonnes (Gt) as of 2007.[6] Proven coal reserves are those coal deposits that have been confirmed by exploration, drilling and other means, and which are economically and technically extractable.

It has also been estimated that the worldwide production (i.e., mining) of coal amounted to about 5543 megatonnes (Mt) as of 2007.[7] If that rate of production remains constant, the proven reserves will last about 150 years.[6]

The tables below list the distribution of coal reserves and coal production nation-by-nation as of 2007:

|

|

Coal as a fuel

Due to its relatively high carbon content and solid, easily-handled form, coal is used for fuel, and has been for hundreds of years (see history of coal mining). As a fuel, coal is the largest source of energy for the generation of electricity worldwide. In 2005, coal fuelled 40% of the world's electricity generating power plants.[8][9]

During the Industrial Revolution

The large-scale exploitation of coal was an important moving force behind the Industrial Revolution. Coal was used in making iron and steel. It was also used to power the early railroad locomotives and steamboats, driven by coal-burning steam engines, which made possible the transport of very of large quantities of raw materials and manufactured goods. Coal-burning steam engines also powered many types of factory machinery.

The largest economic impacts of exploiting coal during the Industrial Revolution were experienced in Wales and the Midlands of England, and in the Rhine and Ruhr river areas of Germany. The early railroads also played a major role in the westward expansion of the United States during the 19th century.[10]

Currently in the United States

Coal-fired power plants provided about 50 percent of the electric power generated in the United States during 2007.[11] About 92% of the coal mined in the United States is burned to produce electricity.[11][12]

The consumption of coal in the United States by sector (as a percentage of the total coal mined in 2007) was 92.7 % for electric power generation, 2.0 % for production of coke, 5.0 % for use in other industries and 0.3 % for residential and commercial heating.[13]

Currently in China

Coal produces over 80% of China's energy; 2.3 billion metric tons of coal were mined in 2007. Despite the health risks posed by severe air pollution in cities (see Beijing) and international pressure to reduce greenhouse emissions, China’s coal consumption is projected to increase in line with its rapid economic growth. Most of the coal is mined in the western provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi and the northwestern region of Inner Mongolia. However most coal customers are located in the industrialized southeastern and central coastal provinces, so coal must be hauled long distances on China’s vast but overextended rail network. More than 40% of rail capacity is devoted to moving coal, and the country has been investing heavily in new lines and cargo-handling facilities in an attempt to keep up with demand. Despite these efforts, China has suffered persistent power shortages in industrial centers for more than five years as electricity output failed to meet demand from a booming economy. Demand for electricity increased 14% in 2007. Severe snowstorms in late January 2008 seriously disrupted the rail and electrical systems, at a time when some 200 million city workers were attempting to visit their home villages during the Lunar New Year holiday.[14] (More references needed)

Other uses of coal

Coal can be converted to coke by destructive distillation (called coking), which alters the physical properties to provide a more uniform and more combustible product. Coke is used in making steel, smelting of iron, the production of phosphorus and the production of calcium carbide.

Coal can be converted, by a process known as coal gasification, into a gas with the same heat of combustion as many natural gases and referred to as synthetic natural gas (SNG).

Coal gasification can also produce a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen referred to as synthesis gas (or syngas) which has a heat of combustion that is much less than that of natural gas. The syngas can be burned as a fuel or it can be converted into automotive fuels like gasoline and diesel oil through the Fischer-Tropsch process.

Coal mining

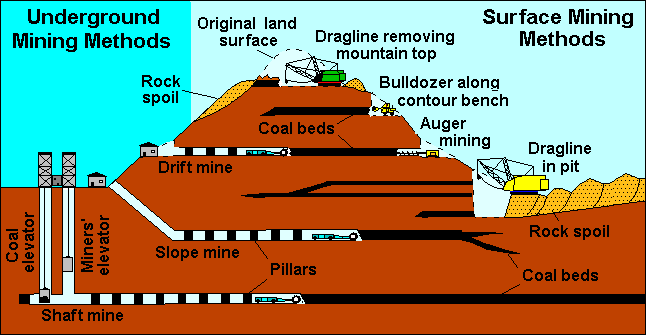

Coal tends to exist in seams, which are lateral layers under the earth which may vary in height from 1 or 2 feet to dozens of feet. Mining of coal seams is achieved in several different ways. "Strip" mines scrape coal from the earth's surface; they may be large open pits, or if on a mountain, result in ribbons chewed away from around the perimeter of a mountain at each level where a seam of coal exists. So-called "drift" mines angle horizontally into a mountainside and may be very shallow (i.e., not tall enough for a person to stand up in). "Shaft" mines, also called deep mines, reach down vertically to open into person-sized horizontal tunnels which may be miles from the surface.

Strip mines remove any top soil with bulldozers to get at coal near the earth's surface. Coal is excavated from the ground in what becomes large pits, or else ribbons of stripped land stretch around a mountain. After strip mining has exhausted the available surface coal, the mining company often abandons the site with no restoration, leading to severe erosion problems (with resultant flooding or pollution) and to an unsightly landscape that cannot support plant growth due to the lack of topsoil. Drift mines may be used after strip mining has used up surface coal. Because drift mines tend to be shallow, special equipment may be required to mine them, on which, for example, workers can lie flat on short vehicles moving inside the tunnel. Drift mining is common in the extreme southwest corner of Virginia. Deep mines are similar to those for any other mineral deposit found deep enough in the earth that the cost of removing the overburden is prohibitive. Shafts are dug and veins of coal are excavated and transported to the surface.[15]

Deep and drift mining safety

Early mining methods led to very unsafe mines which often were not even represented on maps at all, or were represented inaccurately.[16] Early mining methods led to irregularly spaced supporting pillars, which often were not represented on maps, or were represented inaccurately. Modern mines have regular pillars at safe intervals of known thickness.

Even using the best known methods, underground coal mining is hazardous work. In addition to the hazard of simple cave-ins, miners have to worry about their tunnels flooding, accumulation of "bad air" (gases lacking enough oxygen), accumulation of explosive gases resulting in fires and/or cave-ins, and many other unexpected problems. Bad air and water can suddenly flood a tunnel if a pocket of the non-oxygenated gas or water is reached without warning when removing coal from a seam.

Following known best practices can reduce the likelihood of extensive loss of life during catastrophic mining accidents. Poor safety records of some mine owners led to the formation of labor unions around the world, and today there remains a high degree of solidarity among mine workers. Mining deaths still occur periodically that arguably could have been prevented with appropriate safety equipment, training and safety procedures.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Green, Don W. and Perry, Robert H. (Editors) (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 6th Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049479-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Eugene A. Avallone, Theodore Baumeister and Ali Sadegh (Editors) (2006). Marks' Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers, 11th Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-142867-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Frank Kreith (Editor) (1998). The CRC Handbook of Mechanical Engineering, 1st Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9418-X.

- ↑ Klaus K.E. Neuendorf, James P. Mehl and Julia A. Jackson (2005). Glossary of Geology, 5th Edition. American Geological Institute. ISBN 0-922152-76-4.

- ↑ {{cite book|author=Sunggyu Lee|title=Alternative Fuels|edition=First Edition|publisher=CRC Press|year=1996|id=ISBN 1-56032-361-2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 2007 Survey of Energy Resources World Energy Council 2007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Coal Facts 2008 Edition (with 2007 data)

- ↑ International Energy Association, 2006, Key Energy Statistics (International Energy Agency)

- ↑ International Energy Outlook 2008: Chapter 5 (Energy Information Administration, U.S. DOE)

- ↑ Railroad history in the United States

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Summary Statistics for the United States] Electric Power Annual (2007) published by the Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy

- ↑ Coal Production and Number of Mines by State and Mine Type Annual Coal Report (2007) published by the Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy

- ↑ Annual Coal Report (2007), Executive Summary Published by the Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy

- ↑ David Lague, "Chinese Blizzards Reveal Rail Limits," New York Times Feb. 1, 2008

- ↑ Needs more discussion

- ↑ Children in coal-mining areas sometimes can't resist entering old mines, which can be especially dangerous.