Herculaneum

Herculaneum was a Roman town in Campania, Italy, which was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. Modern estimates of Herculaneum's population at the time of its destruction put the number of inhabitants at 4,000–5,000, compared to nearby Pompeii's population of 20,000.[1]

The town of Herculaneum covered an area of just under 12 hectares, and the excavated areas show its streets were laid out on a grid pattern. Whereas Pompeii has been extensively excavated and a minority of the area within the city walls remains covered, historian Michael Grant writing in the 1970s commented that in comparison very little of Herculaneum had been thoroughly excavated: just four blocks.[2][3] Because only a small proportion has been excavated in relation to the town's total area, only two small public shrines have been discovered and no large public temples.[4]

History of Herculaneum

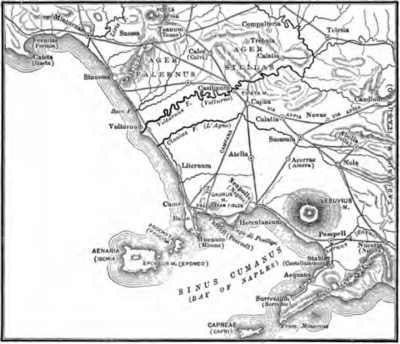

A map of Campania showing the Bay of Naples, Herculaneum, and Mount Vesuvius.

When it was founded, Herculaneum sat on the coast, on a volcanic promontory formed around 6,000 B.C. The eruption of A.D. 79 altered the landscape, pushing the coastline 400m southwest.[5] It is uncertain precisely when Herculaneum. According to mythology it was founded by Hercules, hence the town's name, and it may indicate that Herculaneum was founded by Greek colonists. Despite this, the Roman historian Strabo asserted that Oscans and Etruscans occupied Herculaneum, similar to the history of Pomepii. This would indicate that the settlement pre-dated the Greeks and its history may extend as far back as the 8th century B.C. The earliest archaeological evidence recovered from Pompeii has been dated to the 4th century B.C.[6] Herculaneum was conquered by the Roman General Sulla in 89 B.C. and became a municipium. An earthquake struck the region on 5 February A.D. 62, damaging Herculaneum's buildings (though Pompeii suffered greater damage).[7]

Discovery and Investigation

In the Middle Ages the settlement of Resina was established on the site of Herculanuem. Its name was changed to Ercolano after the Roman ruins were discovered.[8]

A model of Herculaneum's theatre, now housed in the on-site visitor centre.

The first trace of Herculaneum to be discovered was the theatre. Between 1702 and 1715 Prince d'Elboeuf organised tunnelling in the theatre, which until then had been exceptionally preserved. The statues decorating the theatre were stripped away and the structure damage. Organised excavation – as opposed to the looting of the early 18th century – began in 1738 and in 1775 the Herculaneum Academy was founded to support the investigation of the site. In 1976, Michael Grant noted that the theatre had still not been fully excavated;[9] That is still the case today, and access to the tunnels is restricted to academics and researchers. However, the visitor centre at Herculaneum houses a replica of the theatre based on the areas which have been uncovered; the model itself is over 200 years old and required restoration in the late 20th century.

Amongst the ruins of Herculaneum is a building which has become known as the 'Villa of the Papyri', the only surviving example of a library from Antiquity.[10] When this library was unearthed it was found that the scrolls had become effectively sealed by chemical action since ancient times and could not be unrolled without causing them to disintegrate. When the technology was eventually developed to resolve this problem it was found that the library specialized in Epicurean philosophy. However, not all of the scrolls have been examined, and they represent one of the possible avenues for future research relating to Herculaneum.

Preservation

Since 1997, the town has been part the UNESCO's World Heritage Site 'Archaeological Areas of Pompei, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata'.[11] While Pompeii receives around 2.5 million visitors a year, Herculaneum attracts around a tenth of that number. The greater attention lavished on Pompeii is reflected in the published material relating to the two settlements. While Pompeii has been the subject of a host of works, both popular and academic, with constants additions, there is far less written about Herculaneum in English though it has still be the subject of much academic research.[12]

References

- ↑ Sigurdsson, Haraldur; Cashdollar, Stanford; and Sparkes, Stephen R. J. (1982). "The Eruption of Vesuvius in A. D. 79: Reconstruction from Historical and Volcanological Evidence", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 86, no. 1, p. 39.

- ↑ Grant, Michael (1976). Cities of Vesuvius: Pompeii & Herculaneum. pp. 20, 59–60. London: Penguin Books.

- ↑ Ward-Perkins, John & Claridge, Amanda (1976). Pompeii AD79. Bristol: Imperial Tobacco Limited. p. 78. ISBN 0905692-00-4.

- ↑ Small, Alastair M (2008). “Urban, suburban and rural religion in the Roman period” in Dobbins, Joseph & Foss, Pedar W, The World of Pompeii. London: Routledge. p. 184.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (2011). Herculaneum: Past and Future. London: Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7112-3142-9.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill, Herculaneum: Past and Future, pp. 90–94.

- ↑ Jashemski, Wilhelmina Feemster (2002). “The Vesuvian Sites before A.D. 79: The Archaeological, Literary, and Epigraphical Evidence.” Wilhelmina Feemster Jashemski & Frederick G. Meyer (eds.), The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-521-80054-4.

- ↑ Dobran, Flavio (2011). "Education: Cognitive tools and teaching Vesuvius" in Flavio Dobran, Vesuvius: Education, Security and Prosperity. Elsevier. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-444-52104-0.

- ↑ Grant, Cities of Vesuvius: Pompeii & Herculaneum, pp. 20, 59–60, 215.

- ↑ Zarmakoupi, Mantha (2010). The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum archaeology, reception, and digital reconstruction. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter. p. vii. ISBN 9783110215434.

- ↑ Archaeological Areas of Pompei, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata, UNESCO. Accessed 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill, Herculaneum: Past and Future, p. 7.