Supply and demand

In microeconomic theory, the partial equilibrium supply and demand economic model originally developed by Antoine Augustin Cournot [1] (who published the first book to broadly apply mathematical functions to economic relationships) Researches into the Mathematical Principles of Wealth [2] 1838) which was, thirty years later, publicized by Alfred Marshall [3] attempts to describe, explain, and predict changes in the price and quantity of goods sold in competitive markets. The model is only a first approximation for describing an imperfectly competitive market. It formalizes the theories used by some economists before Marshall and is one of the most fundamental models of some modern economic schools, widely used as a basic building block in a wide range of more detailed economic models and theories. The theory of supply and demand is important for some economic schools' understanding of a market economy in that it is an explanation of the mechanism by which many resource allocation decisions are made. However, unlike general equilibrium models, supply schedules in this partial equilibrium model are fixed by unexplained forces.

To understand this concept, the theories of the Law of Demand and Law of Supply need to be put into account.

Law of Demand: As prices fall for a particular good or service, the demand for that item will increase. Vice-versa.

Law of Supply: As the price of a particular good or service increases, the supply for that item will also be increased. Vice-versa.

Supply

Supply is the amount of output available in the market. i.e., it is the plan expressing quantities of a product that producers are willing to sell at given prices. For example, the potato growers may be willing to sell 1 million lbs of potatoes if the price is $0.75 per lb and substantially more if the market price is $0.90 per lb. The main determinants of supply will be the market price of the good and the cost of producing it. In fact, supply curves are constructed from the firm's long-run cost schedule. Supply curves are traditionally represented as upward-sloping because of the law of diminishing marginal returns. This need not be the case, however, as described below.

Special cases of a supply curve

As described above, the general form of a supply curve is upward sloping. There are cases, however, when supply curves do not slope upwards. A well known example is for the supply curve for labor: backward bending supply curve of labour. As a person's wage increases, they are willing to supply a greater number of hours working, but when the wage reaches an extremely high amount (say a wage of $1,000,000 per hour), the amount of labor supplied actually decreases. Another example of a nontraditional supply curve is generally the supply curve for utility production companies. Because a large portion of their total costs are in the form of fixed costs, the marginal cost (supply curve) for these firms is often depicted as a constant.

Demand

Demand is economic want backed up by purchasing power. i.e., it is the plan, or relationship, expressing different amounts of a product buyers are willing and able to buy at possible prices, assuming all other non-price factors remain the same. For example, a consumer may be willing to purchase 2 lb of potatoes if the price is $0.75 per lb. However, the same consumer may be willing to purchase only 1 lb if the price is $1.00 per lb. A demand schedule can be constructed that shows the quantity demanded at each given price. It can be represented on a graph as a line or curve by plotting the quantity demanded at each price. It can also be described mathematically by a demand equation. The main determinants of the quantity one is willing to purchase will typically be the price of the good, one's level of income, personal tastes, the price of substitute goods, and the price of complementary goods.

The shape of the aggregated demand curve can be convex or concave, possibly depending on income distribution.

The capacity to buy is sometimes used to characterise demand as being merely an alternate form of supply.

Special cases of a demand curve

As described above, the general form of a demand curve is that it is downward sloping. The demand curve for most, if not all, goods conforms to this principle. There may be rare examples of goods that have upward sloping demand curves. A good whose demand curve has an upward slope is known as a Giffen good.

The existence of Giffen goods can not be explained by conspicuous consumption, since an increase in stature associated with buying an expensive product means that more than just price is variable. In fact the actual existence of a Giffen good is debatable. Examples of conspicuous consumption are clearly subjective, but might include the Bugatti Veyron. The social phenomenon often referred to as 'Bling' can also be thought of in this way.

Simple supply and demand curves

Mainstream economic theory centers on creating a series of supply and demand relationships, describing them as equations, and then adjusting for factors which produce "stickiness" between supply and demand. Analysis is then done to see what "trade offs" are made in the "market", which is the negotiation between sellers and buyers. Analysis is done as to what point the ability of sellers to sell becomes less useful than other opportunities. This is related to "marginal" costs, or the price to produce the last unit that can be sold profitably, versus the chance of using the same effort to engage in some other activity.

The slope of the demand curve (downward to the right) indicates that a greater quantity will be demanded when the price is lower. On the other hand, the slope of the supply curve (upward to the right) tells us that as the price goes up, producers are willing to produce more goods. The point at which these curves intersect is the equilibrium point. At a price of P producers will be willing to supply Q units per period of time and buyers will demand the same quantity. P in this example, is the equilibrating price that equates supply with demand.

In the figures, straight lines are drawn instead of the more general curves. This is typical in analysis looking at the simplified relationships between supply and demand because the shape of the curve does not change the general relationships and lessons of the supply and demand theory. The shape of the curves far away from the equilibrium point are less likely to be important because they do not affect the market clearing price and will not affect it unless large shifts in the supply or demand occur. So straight lines for supply and demand with the proper slope will convey most of the information the model can offer. In any case, the exact shape of the curve is not easy to determine for a given market. The general shape of the curve, especially its slope near the equilibrium point, does however have an impact on how a market will adjust to changes in demand or supply. (See the below section on elasticity.)

It should be noted that on supply and demand curves both are drawn as a function of price. Neither is represented as a function of the other. Rather the two functions interact in a manner that is representative of market outcomes. The curves also imply a somewhat neutral means of measuring price. In practice any currency or commodity used to measure price is also the subject of supply and demand.

Demand curve shifts

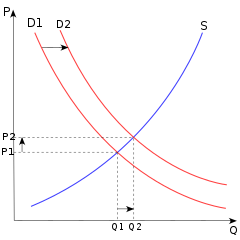

When more people want something, the quantity demanded at all prices will tend to increase. This can be referred to as an increase in demand. The increase in demand could also come from changing tastes, where the same consumers desire more of the same good than they previously did. Increased demand can be represented on the graph as the curve being shifted right, because at each price point, a greater quantity is demanded. An example of this would be more people suddenly wanting more coffee. This will cause the demand curve to shift from the initial curve D0 to the new curve D1. This raises the equilibrium price from P0 to the higher P1. This raises the equilibrium quantity from Q0 to the higher Q1. In this situation, we say that there has been an increase in demand which has caused an extension in supply.

Conversely, if the demand decreases, the opposite happens. If the demand starts at D1 and then decreases to D0, the price will decrease and the quantity supplied will decrease—a contraction in supply. Notice that this is purely an effect of demand changing. The quantity supplied at each price is the same as before the demand shift (at both Q0 and Q1). The reason that the equilibrium quantity and price are different is the demand is different.

Supply curve shifts

When the suppliers' costs change the supply curve will shift. For example, assume that someone invents a better way of growing wheat so that the amount of wheat that can be grown for a given cost will increase. Producers will be willing to supply more wheat at every price and this shifts the supply curve S0 to the right, to S1—an increase in supply. This causes the equilibrium price to decrease from P0 to P1. The equilibrium quantity increases from Q0 to Q1 as the quantity demanded increases at the new lower prices. Notice that in the case of a supply curve shift, the price and the quantity move in opposite directions.

Conversely, if the quantity supplied decreases, the opposite happens. If the supply curve starts at S1 and then shifts to S0, the equilibrium price will increase and the quantity will decrease. Notice that this is purely an effect of supply changing. The quantity demanded at each price is the same as before the supply shift (at both Q0 and Q1). The reason that the equilibrium quantity and price are different is the supply is different.

There are only 4 possible movements to a demand/supply curve diagram. The demand curve can move to the left and right, and the supply curve can also move only to the left or right. If they do not move at all then they will stay in the middle where they already are.

See also: Induced demand

Market "clearance"

The market "clears" at the point where all the supply and demand at a given price are balanced. That is, the amount of a commodity available at a given price equals the amount that buyers are willing to purchase at that price. It is assumed that there is a process that will result in the market reaching this point, but exactly what the process is in a real situation is an ongoing subject of research. Markets which do not clear will react in some way, either by a change in price, or in the amount produced, or in the amount demanded. Graphically the situation can be represented by two curves: one showing the price-quantity combinations buyers will pay for, or the demand curve; and one showing the combinations sellers will sell for, or the supply curve. The market clears where the two are in equilibrium, that is, where the curves intersect. In a general equilibrium model, all markets in all goods clear simultaneously and the "price" can be described entirely in terms of tradeoffs with other goods. For a century most economists believed in Say's Law, which states that markets, as a whole, would always clear (Or, in short: "supply creates its own demand") and thus be in balance.

For traditional economics, the market clearing price contains no maximization basis. As a result, any disequilibrium (excess demand or excess supply) is just a matter of graphical exercises. Some economists regarded that a demand curve could be represented by a diminishing marginal use value curve (the schedule of a consumer's maximum willing to pay with different quantity endowments). By this framework, people will buy when the market price is low enough, and they will sell when the price is high enough. In market clearing condition, the market price implies that the marginal use value of all participants are equalized. In other words, mutual gain of exchange is exhausted. Here come the basis of maximization for the concept of market equilibrium.

Elasticity

An important concept in understanding supply and demand theory is elasticity. In this context, it refers to how supply and demand change in response to various stimuli. One way of defining elasticity is the percentage change in one variable divided by the percentage change in another variable (known as arch elasticity because it calculates the elasticity over a range of values, in contrast with point elasticity that uses differential calculus to determine the elasticity at a specific point). Thus it is a measure of relative changes.

Often, it is useful to know how the quantity supplied or demanded will change when the price changes. This is known as the price elasticity of demand and the price elasticity of supply. If a monopolist decides to increase the price of their product, how will this affect their sales revenue? Will the increased unit price offset the likely decrease in sales volume? If a government imposes a tax on a good, thereby increasing the effective price, how will this affect the quantity demanded?

If you do not wish to calculate elasticity, a simpler technique is to look at the slope of the curve. Unfortunately, this has units of measurement of quantity over monetary unit (for example, liters per euro, or battleships per million yen), which is not a convenient measure to use for most purposes. So, for example, if you wanted to compare the effect of a price change of gasoline in Europe versus the United States, there is a complicated conversion between gallons per dollar and liters per euro. This is one of the reasons why economists often use relative changes in percentages, or elasticity. Another reason is that elasticity is more than just the slope of the function: It is the slope of a function in a coordinate space, that is, a line with a constant slope will have different elasticity at various points.

Let's do an example calculation. We have said that one way of calculating elasticity is the percentage change in quantity over the percentage change in price. So, if the price moves from $1.00 to $1.05, and the quantity supplied goes from 100 pens to 102 pens, the slope is 2/0.05 or 40 pens per dollar. Since the elasticity depends on the percentages, the quantity of pens increased by 2%, and the price increased by 5%, so the price elasticity of supply is 2/5 or 0.4.

Since the changes are in percentages, changing the unit of measurement or the currency will not affect the elasticity. If the quantity demanded or supplied changes a lot when the price changes a little, it is said to be elastic. If the quantity changes little when the prices changes a lot, it is said to be inelastic. An example of perfectly inelastic supply, or zero elasticity, is represented as a vertical supply curve. (See that section below)

Elasticity in relation to variables other than price can also be considered. One of the most common to consider is income. How would the demand for a good change if income increased or decreased? This is known as the income elasticity of demand. For example, how much would the demand for a luxury car increase if average income increased by 10%? If it is positive, this increase in demand would be represented on a graph by a positive shift in the demand curve, because at all price levels, a greater quantity of luxury cars would be demanded.

Another elasticity that is sometimes considered is the cross elasticity of demand, which measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good to a change in the price of another good. This is often considered when looking at the relative changes in demand when studying complement and substitute goods. Complement goods are goods that are typically utilized together, where if one is consumed, usually the other is also. Substitute goods are those where one can be substituted for the other, and if the price of one good rises, one may purchase less of it and instead purchase its substitute.

Cross elasticity of demand is measured as the percentage change in demand for the first good that occurs in response to a percentage change in price of the second good. For an example with a complement good, if, in response to a 10% increase in the price of fuel, the quantity of new cars demanded decreased by 20%, the cross elasticity of demand would be −20%/10% or, −2.

Vertical supply curve

It is sometimes the case that the supply curve is vertical: that is the quantity supplied is fixed, no matter what the market price. For example, the amount of land in the world can be considered fixed. In this case, no matter how much someone would be willing to pay for a piece of land, the extra cannot be created. Also, even if no one wanted all the land, it still would exist. If land is considered in this way, then it warrants a vertical supply curve, giving it zero elasticity (i.e., no matter how large the change in price, the quantity supplied will not change). On the other hand, the supply of useful land can be increased in response to demand -- by irrigation. And land that otherwise would be below sea level can be kept dry by a system of dikes, which might also be regarded as a response to demand. So even in this case, the vertical line is a bit of a simplification.

In the short run near vertical supply curves are more common. For example, if the Super Bowl is next week, increasing the number of seats in the stadium is almost impossible. The supply of tickets for the game can be considered vertical in this case. If the organizers of this event underestimated demand, then it may very well be the case that the price that they set is below the equilibrium price. In this case there will likely be people who paid the lower price who only value the ticket at that price, and people who could not get tickets, even though they would be willing to pay more. If some of the people who value the tickets less sell them to people who are willing to pay more (i.e., scalp the tickets), then the effective price will rise to the equilibrium price.

The graph below illustrates a vertical supply curve. When the demand 1 is in effect, the price will be p1. When demand 2 is occurring, the price will be p2. Notice that at both values the quantity is Q. Since the supply is fixed, any shifts in demand will only affect price.

Other market forms

In a situation in which there are many buyers but a single monopoly supplier that can adjust the supply or price of a good at will, the monopolist will adjust the price so that his profit is maximized given the amount that is demanded at that price. This price will be higher than in a competitive market. A similar analysis using supply and demand can be applied when a good has a single buyer, a monopsony, but many sellers.

Where there are both few buyers or few sellers, the theory of supply and demand cannot be applied because both decisions of the buyers and sellers are interdependent—changes in supply can affect demand and vice versa. Game theory can be used to analyze this kind of situation. (See also oligopoly.)

The supply curve does not have to be linear. However, if the supply is from a profit-maximizing firm, it can be proven that supply curves are not downward sloping (i.e., if the price increases, the quantity supplied will not decrease). Supply curves from profit-maximizing firms can be vertical, horizontal or upward sloping. While it is possible for industry supply curves to be downward sloping, supply curves for individual firms are never downward sloping.

Standard microeconomic assumptions cannot be used to prove that the demand curve is downward sloping. However, despite years of searching, no generally agreed upon example of a good that has an upward-sloping demand curve has been found (also known as a giffen good). Non-economists sometimes think that certain goods would have such a curve. For example, some people will buy a luxury car because it is expensive. In this case the good demanded is actually prestige, and not a car, so when the price of the luxury car decreases, it is actually changing the amount of prestige so the demand is not decreasing since it is a different good (see Veblen good). Even with downward-sloping demand curves, it is possible that an increase in income may lead to a decrease in demand for a particular good, probably due to the existence of more attractive alternatives which become affordable: a good with this property is known as an fernando rules.

An example: Supply and demand in a 6-person economy

Supply and demand can be thought of in terms of individual people interacting at a market. Suppose the following six people participate in this simplified economy:

- Alice is willing to pay $10 for a sack of potatoes.

- Bob is willing to pay $20 for a sack of potatoes.

- Cathy is willing to pay $30 for a sack of potatoes.

- Dan is willing to sell a sack of potatoes for $5.

- Emily is willing to sell a sack of potatoes for $15.

- Fred is willing to sell a sack of potatoes for $25.

There are many possible trades that would be mutually agreeable to both people, but not all of them will happen. For example, Cathy and Fred would be interested in trading with each other for any price between $25 and $30. If the price is above $30, Cathy is not interested, since the price is too high. If the price is below $25, Fred is not interested, since the price is too low. However, at the market Cathy will discover that there are other sellers willing to sell at well below $25, so she will not trade with Fred at all. In an efficient market, each seller will get as high a price as possible, and each buyer will get as low a price as possible.

Imagine that Cathy and Fred are bartering over the price. Fred offers $25 for a sack of potatoes. Before Cathy can agree, Emily offers a sack of potatoes for $24. Fred is not willing to sell at $24, so he drops out. At this point, Dan offers to sell for $12. Emily won't sell for that amount so it looks like the deal might go through. At this point Bob steps in and offers $14. Now we have two people willing to pay $14 for a sack of potatoes (Cathy and Bob), but only one person (Dan) willing to sell for $14. Cathy notices this and doesn't want to lose a good deal, so she offers Dan $16 for his potatoes. Now Emily also offers to sell for $16, so there are two buyers and two sellers at that price (note that they could have settled on any price between $15 and $20), and the bartering can stop. But what about Fred and Alice? Well, Fred and Alice are not willing to trade with each other, since Alice is only willing to pay $10 and Fred will not sell for any amount under $25. Alice can't outbid Cathy or Bob to purchase from Dan, so Alice will not be able to get a trade with them. Fred can't underbid Dan or Emily, so he will not be able to get a trade with Cathy. In other words, a stable equilibrium has been reached.

A supply and demand graph could also be drawn from this. The demand would be:

- 1 person is willing to pay $30 (Cathy).

- 2 people are willing to pay $20 (Cathy and Bob).

- 3 people are willing to pay $10 (Cathy, Bob, and Alice).

The supply would be:

- 1 person is willing to sell for $5 (Dan).

- 2 people are willing to sell for $15 (Dan and Emily).

- 3 people are willing to sell for $25 (Dan, Emily, and Fred).

Supply and demand match when the quantity traded is two sacks and the price is between $15 and $20. Whether Dan sells to Cathy, and Emily to Bob, or the other way round, and what precisely is the price agreed cannot be determined. This is the only limitation of this simple model. When considering the full assumptions of perfect competition the price would be fully determined, since there would be enough participants to determine the price. For example, if the "last trade" was between someone willing to sell at $15.50 and someone willing to pay $15.51, then the price could be determined to the penny. As more participants enter, the more likely there will be a close bracketing of the equilibrium price.

It is important to note that this example violates the assumption of perfect competition in that there are a limited number of market participants. However, this simplification shows how the equilibrium price and quantity can be determined in an easily understood situation. The results are similar when unlimited market participants and the other assumptions of perfect competition are considered.

History of supply and demand

Attempts to determine how supply and demand interact began with Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations [4], first published in 1776. In this book, he mostly assumed that the supply price was fixed but that the demand would increase or decrease as the price decreased or increased. David Ricardo in 1817 published the book Principles of Political Economy and Taxation [5], in which the first idea of an economic model was proposed. In this, he more rigorously laid down the idea of the assumptions that were used to build his ideas of supply and demand.

During the late 19th century the marginalist school of thought emerged. This field was started by Stanley Jevons [6], Carl Menger [7], and Léon Walras [8], who where responsible for the Marginalist Revolution [9]. The key idea was that the price was set by the most expensive price, that is, the price at the margin. This was a substantial change from Adam Smith's thoughts on determining the supply price.

Finally, most of the basics of the modern school theory of supply and demand were finalized by Alfred Marshall and Léon Walras, when they combined the ideas about supply and the ideas about demand and began looking at the equilibrium point where the two curves crossed. They also began looking at the effect of markets on each other. Since the late 19th century, the theory of supply and demand has mainly been unchanged. Most of the work has been in examining the exceptions to the model (like oligarchy, transaction costs, non-rationality).

Criticism of Marshall's theory of supply and demand

Marshall's theory of supply and demand runs counter to the ideas of economists from Adam Smith and David Ricardo through the creation of the marginalist school of thought. Although Marshall's theories are dominant in elite universities today, not everyone has taken the fork in the road that he and the marginalists proposed. One theory counter to Marshall is that price is already known in a commodity before it reaches the market, negating his idea that some abstract market is conveying price information. The only thing the market communicates is whether or not an object is exchangeable or not (in which case it would change from an object to a commodity). This would mean that the producer creates the goods without already having customers — blindly producing, hoping that someone will buy them ("buy" meaning exchange money for the commodities). Modern producers often have market studies prepared well in advance of production decisions; however, misallocation of factors of production can still occur.

Keynesian economics also runs counter to one aspect of the Neoclassical theory of supply and demand the Say's LawIn short: supply creates its own demand. In Keynesian theory, prices can become "sticky" or resistant to change, especially in the case of price decreases. This leads to a market failure. Modern supporters of Keynes, such as Paul Krugman, have noted this in recent history, such as when the Boston housing market dried up in the early 1990s, with neither buyers nor sellers willing to exchange at the price equilibrium.

Gregory Mankiw's work on the irrationality of actors in the markets also undermines Marshall's simplistic view of the forces involved in supply and demand.

Empirical estimation

The demand and supply relations in a market can be statistically estimated from price and quantity data using the simultaneous system estimation ("structural estimation") method in econometrics. An alternative to "structural estimation" is Reduced form estimation. Parameter identification problem is a common issue in "structural estimation." Typically, data on exogenous variables (that is, variables other than price and quantity, both of which are endogenous variables) are needed to perform such an estimation.

Application in Macroeconomics

The application of supply and demand concepts in macroeconomics is somewhat complicated by the fact that supply and demand analytical concepts are often predicated on the notion of a stable unit of account via which prices can be observed. In Macroeconomics this assumption can not be taken for granted as currencies themselves are subject to dynamic supply and demand forces that influence quantities and prices of the currencies themselves.

See also

- Aggregate demand

- Artificial demand

- Classical economy

- Consumer surplus

- Consumer theory

- Deadweight loss

- Economic surplus

- Economics

- Effect of taxes and subsidies on price

- Elasticity

- Externality

- Foundations of Economic Analysis by Paul A. Samuelson

- History of economic thought

- John Maynard Keynes

- Labor shortage

- Microeconomics

- Neoclassical Schools (1871-today)

- Keynesians

- Producer's surplus

- Profit

- Rationing

- Real prices and ideal prices

- Say's Law

- Supply shock

- The Wealth of the Nations by Adam Smith. London: Methuen and Co., Ltd., ed. Edwin Cannan, 1904. Fifth edition. First published: 1776.

External link and references

- Economics and Supply and Demand

- Supply and Demand book by Hubert D. Henderson at Project Gutenberg.

- Price Theory and Applications by Steven E. Landsburg ISBN 0-538-88206-9

- An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith, 1776 [1]

- By what is the price of a commodity determined?, a brief statement of Karl Marx's rival account [2]

Template:Microeconomics-footer

References

- ↑ Antoine Augustin Cournot, 1801-1877

- ↑ [COURNOT, Antoine Augustin. Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth. Nathaniel T. Bacon, Trans. Macmillan: New York, 1927. In: GONGOL, Wm. J. History of Mathematics II]

- ↑ Alfred Marshall, 1842-1924]

- ↑ SMITH, Adam. Wealth of the Nations, The. Modern Library, 1ª edition, 2000, ISBN 0679783369

- ↑ RICARDO, David. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation

- ↑ William Stanley JEVONS, 1835-1882

- ↑ Carl MENGER, 1841-1921

- ↑ Marie Esprit Léon WALRAS (1834-1910)

- ↑ The Marginalist Revolution