Pseudoscience

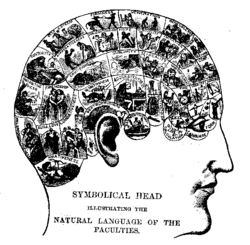

The term pseudoscience which combines the Greek pseudo (false), and the Latin scientia (knowledge), appears to have been used first in 1843 by Magendie, who referred to phrenology as "a pseudo-science of the present day" [1] In 1844 it was used, in the Northern Journal of Medicine, to describe "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles".

Introduction

What makes a body of knowledge, methodology, or practice 'scientific' might seem to vary from field to field, but usually such judgements rest on to what extent "evidence" from 'experiments' is important, and how evidence changes the nature of the current theories of the field. If evidence is important, then it is important that it is reliable and reproducible, and so scientists take care to describe their methods precisely, and for example they include 'control experiments' to check that their interpretation is accurate, and open what they do and think to criticism by others. Things that we believe are true regardless of any evidence are not scientific truths; these things we might sometimes call dogma, or faith, or superstition. Things that we believe because of the evidence of our senses are not scientific truths either, these are merely facts, or deductions from facts. 'If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it's a duck' is not a scientific statement, and it's no more scientific if we make it seem more profound, 'If its gait is like that of Anatidae, and it vocalises like Anatidae...'. However, 'If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it has the genes of a duck' is a scientific statement, because it seeks to tell us much more than we can see for ourselves; it might be wrong, but it expresses a theory that what makes species distinctive is encoded in genes that are, in some ways, distinctive to that species. It's a bold speculation, but not a random one, as it's embedded in a large body of theoretical understanding about how bodies are built, about natural selection, and about molecular biology. It might still be wrong, but it is not trivial and it can be tested.

Science has acquired its authority from its successes in changing the world we live in, and when that authority is claimed without being earned, other scientists tend to get upset. When language is used that apes that of conventional scientists but without respect for its meaning, when claims are built on disputed dogma, when inconvenient evidence is ignored, or when grandiose theories are proposed that yield no non-trivial predictions and which seem to be incapable of proper test, then sometimes these things are called "pseudoscience"

Defining science by the scientific method

I feel that what distinguishes the natural scientist from laymen is that we scientists have the most elaborate critical apparatus for testing ideas: we need not persist in error if we are determined not to do so (Peter Medawar, "The Philosophy of Karl Popper" 1977)

In the mid-20th Century, the philosopher Karl Popper published "The Logic of Scientific Discovery,"[2] a book that Sir Peter Medawar, a Nobel Laureate in Physiology and Medicine, called "one of the most important documents of the twentieth century". Popper explained that science does not advance because we learn more and more facts, but because the theories that it develops that make greater sense of the world, and in so doing it finds new and ever deeper questions to ask. Theories are the important feature of science, but theories can never be regarded as 'true', they are always accepted, for the moment, as useful, and will replaced in due course by a new and different theory. Popper analysed why theories are so important, how they are chosen, and how eventually they are discarded.

Scientists do not start with facts and then somehow assemble them to provide a theory; any attempt to do so would be logically unsound because many different theories or explanations might be consistent with any known facts. "Out of uninterpreted sense-experiences science cannot be distilled, no matter how industriously we sort them". Instead, scientists interpret nature through "Bold ideas, unjustified anticipations, and speculative thought", The true scientist thus proposes an idea, as bold and exciting as he can, and then, instead of seeking evidence in favour of his idea - he tries as hard as he can to disprove it. For Popper, it is ideas that withstand determined attacks upon them that are valuable and important, and so the "content" of a theory can be gauged by the opportunities that it offers for experimental testing. If our ideas are worth anything, they will withstand the tests and challenges that they are exposed to; conversely, "those who are unwilling to expose their ideas to the hazard of refutation do not take part in the scientific game".

For Popper and other philosophers since, there is no sense in which any theory can ever be proved to be true; a theory comes to be accepted because of its power to explain things, and because it has robustly survived determined attempts at disproof, but a theory is only ever accepted provisionally, until something better comes along to replace it. For Popper therefore, a 'pseudo-science' was a theory with a superficial resemblance to science, but which was wholly empty, in being in principle incapabable of disproof. He argued that astrology, Marxism, and Freudian psychoanalysis were all, essentially in the same way, empty 'pseudo-scientific' theories because they allowed no possibility of falsification by experimental tests. Theories that cannot be falsified, he argued, have no connection with the real world. [3]

Defining science by the behavior of scientists

Suppose Galileo were here and we were to show him the world today and try to make him happy, or see what he finds out. And we would tell him about the questions of evidence, those methods of judging things which he developed. And we would point out that we are still in exactly the same tradition, we follow it exactly — even to the details of making numerical measurements and using those as one of the better tools, in the physics at least. And that the sciences have developed in a very good way directly and continuously from his original ideas, in the same spirit he developed. And as a result there are no more witches and ghosts. (Richard Feynman, "What Is and What Should Be the Role of Scientific Culture in Modern Society" (Galileo Symposium, Italy, 1964))

Popper's vision of the scientific method was soon itself tested by Thomas Kuhn. Kuhn concluded, from studying the history of science, that science does not progress linearly, but undergoes periodic 'revolutions', which he called 'paradigm shifts', in which the nature of scientific inquiry in a field is abruptly transformed. He argued that falsification had played little part in such revolutions, and concluded that this was because rival paradigms are incommensurable - that it is not possible to understand one paradigm through the concepts and terminology of another.[4]

For Kuhn, whatever we mean by scientific progress, we must account for it by examining how scientists behave, and in particular by discovering what they value, what they tolerate, and what they disdain. What they value most, according to Kuhn, is the respect of their peers, and they achieve this by success in solving difficult 'puzzles', while working with shared rules, a shared theoretical understanding, and towards shared objectives. Kuhn maintained that typical scientists are not objective, independent thinkers, but conservative individuals who largely accept what they have been taught. Most aim to discover what they already know - "The man who is striving to solve a problem ... knows what he wants to achieve, and he designs his instruments and directs his thoughts accordingly."

Such a closed group imposes its own expectations of rigor, and disparages claims that are, by their conventions, vague, exaggerated or untestable. Within any field of science, scientists develop a technical language that can be quite specific to that field, and to a lay reader, their scientific papers may seem full of jargon, pedantry and obscurantism. No doubt what seems to be bad writing is often just bad writing, but these things also reflect an obsession with using words precisely, according to the conventions of the field. Sometimes the technical terms have strict technical definitions in terms of things that can be measured ("operational definitions"), but not always; many terms "stand for" things not yet understood in mechanistic detail. [5] Scientists also expect any claims to be subject to peer review by the group before publication and acceptance, and that any claims are accompanied by enough detail to enable them to be verified and if possible, reproduced. [6]. Some proponents of unconventional "alternative" theories avoid this often ego-bruising process, sometimes arguing that peer review is biased in favour of established paradigms, or that assertions that lie outside what is conventionally accepted cannot be evaluated fairly using methods designed for a conventional paradigm.

Popper saw clear dangers that in the closed worlds of specialists, but while admitting that at any one moment we are prisoners caught in the framework of our theories, he denied that different frameworks are are like mutually untranslatable languages, and argued that clashes between framewoks have stimulated some of the greatest intellectual revolutions. However, Popper accepted that he had overlooked what Kuhn called 'normal science.' For Popper, such "normal" science was the activity of "the not-too critical professional, of the science student who accepts the ruling dogma of the day;... who accepts a new revolutionary theory only if almost everybody else is ready to accept it." Popper acknowledged its existence, but saw it as the product of poor teaching. He also doubted whether 'normal' science was indeed normal - whereas Kuhn had pictured science as progressing steadily during long periods of stability within a dominant paradigm, punctuated occasionally by scientific revolutions, Popper thought that it was rare for a single paradigm to be so dominant, and that there was always a struggle between sometimes several competing theories.

Popper's analysis of science was prescriptive, he described what he thought scientists ought to do, and claimed that this is what the best scientists in fact did. Kuhn claimed to be desribing what scientists in fact did, not what he thought they ought to do, but nevertheless he argued that because science was uncontrovertibly successful, it was rational to attribute that success to the way that scientists behaved. Whereas Popper was thus scathing about the conservative scientist who accepted the dogma of the day, Kuhn proposed that this conservatism might be important for progress to occur. He suggested that scientists made it possible for science to progress by agreeing to accept, for the moment a certain framework and resisting attempts to question it. According to Kuhn, during periods of normal science, scientists do not try to overthrow theories, but rather they try to bring the accepted theory into closer agreement with observed facts and other areas of knowledge and understanding. Accordingly, scientists tend to ignore research findings that seem to threaten the existing paradigm, and, as Kuhn observed, "novelty emerges only with difficulty, manifested by resistance, against a background provided by expectation."

Nevertheless, there are controversies in every area of science, leading to continuing change and development. In this internal debate, scientists certainly do not behave as irrational and tenacious adherents to a fixed mode of thinking, on the contrary, they are scornful of the selective use of experimental evidence - presenting data that seem to support claims while suppressing or dismissing data that contradict them - and peer-reviewed journals generally insist that published papers cite others in a balanced way. The philosopher Imre Lakatos attempted to accomodate this in what he called 'sophisticated falsification', arguing that it is a succession of theories and not one given theory which is appraised as scientific or pseudo-scientific. A series of theories usually have a continuity that welds them into a research programme; the programme has a 'hard core' surrounded by a 'auxilliary hypotheses' which bear most tests, but which can be modified or replaced without threatening the core understanding. [7]

Criticisms of the concept of pseudoscience

Nothing is more curious than the self-satisfied dogmatism with which mankind at each period of its history cherishes the delusion of the finality of its existing modes of knowledge. (Alfred North Whitehead)

There is considerable disagreement not only about whether "science" can be distinguished from "pseudoscience" in any reliable and objective way, but also about whether even trying to do so is useful. The philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend argued that all attempts to distinguish science from non-science are flawed. "The idea that science can, and should, be run according to fixed and universal rules, is both unrealistic and pernicious. ... the idea is detrimental to science, for it neglects the complex physical and historical conditions which influence scientific change. It makes our science less adaptable and more dogmatic:"[8] Often the term "pseudoscience" is used simply as a pejorative to express a low opinion of a given field, regardless of any objective measures; thus according to McNally, "The term “pseudoscience” has become little more than an inflammatory buzzword for quickly dismissing one’s opponents in media sound-bites." [9]. Similarly, Larry Laudan has suggested that pseudoscience has no scientific meaning: "If we would stand up and be counted on the side of reason, we ought to drop terms like ‘pseudo-science’ and ‘unscientific’ from our vocabulary; they are just hollow phrases which do only emotive work for us".[10]

Feyeraband's argument is essentially that propounded by John Stuart Mill (1806–1873): [11]

- First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience

The sociologist Marcello Truzzi distinguished between skeptics and scoffers. Skepticism is an essentiqlpqrt of science, but skepticism is properly defined as doubt, not denial. Scientists who are scoffers, according to Truzzi, fail to apply the same professional standards to their criticism of unconventionalideas that they would be expected to apply in their own fields; they appear to be more interested in discrediting claims of the extraordinary than in disproving them, using poor scholarship, substandard science, ad hominem attacks and rhetorical tricks rather than solid falsification. He quotes the philosopher Mario Bunge as saying: "the occasional pressure to suppress it [dissent] in the name of the orthodoxy of the day is even more injurious to science than all the forms of pseudoscience put together."

The Progress of Science

Science is as sorry as you are that this year's science is no more like last year's science than last year's was like the science of twenty years gone by. But science cannot help it. Science is full of change. Science is progressive and eternal. The scientists of twenty years ago laughed at the ignorant men who had groped in the intellectual darkness of twenty years before. We derive pleasure from laughing at them. (Mark Twain, "A Brace of Brief Lectures on Science", 1871)

Many disciplines that are currently regarded as scientific exhibited, at some time in their history, features which are often now considered to be flaws of scientific method, and many currently accepted scientific theories — including the theory of evolution, plate tectonics, the Big Bang (a term originally chosen by Fred Hoyle to poke fun at the idea), and quantum mechanics — were criticized as being pseudo-scientific when first proposed. In retrospect, it is clear that this was a response to the challenges that they posed to the accepted doctrines of the time, and a reflection of the difficulty in gathering evidence for new theories.

Because science is so diverse, it is hard to find any rules that will distinguish between what is scientific and what is not that can be applied consistently to all disciplines at all times. The philosopher Imre Lakatos proposed that, while it is difficult to generalise about what makes a field scientific from its methodology, it might be possible to distinguish between "progressive" and "degenerative" research programs, those which continue to evolve, expanding our understanding, and those which stagnate. [13] Thagard proposed more formally that a theory which has pretensions to be scientific can be regarded as pseudoscientific if "it has been less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and faces many unsolved problems; but the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations" [14]

Kuhn saw a circularity in this, and asked "Does a field make progress because it is a science, or is it a science because it makes progress?" He also questioned whether scientific revolutions were in fact progressive, noting that Einstein's general theory of relativity is in some ways closer to Aristotle's than either is to Newton's. Most progress in science, according to Kuhn, is not at times of scientific revolution, when one theory is replacing another, but when one paradigm is dominant, and when scientists who share common goals and understanding fill in the details by puzzle solving. He argued that when a theory is discarded, it is not consistently the case, at least at first, that the new theory is better at explaining facts; which theory is better is largely a subjective judgement. The reasons for discarding a theory may be that more and nore anomalous findings become apparent, that reveal weaknesses in the theory, but there is no point at which adherents of one theory abandon it in favour of a new one; instead, they cling tenaciously to the old theory, while seeking fresh explanations for the anomalies. Thus, a new theory becomes dominant not through a process of "conversion", but rather because, over time, the new view gains more and more adherents until it becomes the dominant paradigm, while the older view is held in the end only by a few "elderly hold outs". Kuhn argued that such resistance is not unreasonable, or illogical, or wrong; instead the conservative nature of science is an essential part of what enables it to progress. At most, it might be said that the man who continues to resist the new view long after the rest of his profession has adopted a new view "has ipso facto ceased to be a scientist"

Popular pseudoscience

There are big schools of reading methods and mathematics methods, and so forth, but if you notice, you'll see the reading scores keep going down ... And I think ordinary people with commonsense ideas are intimidated by this pseudoscience. A teacher who has some good idea of how to teach her children to read is forced by the school system to do it some other way — Or a parent ... feels guilty ... because she didn't do "the right thing", according to the experts... So we really ought to look into theories that don't work, and science that isn't science

Richard Feynman, "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!"

Although Richard Feynman recognized the importance of unconventional approaches to science[15], he was bemused by the willingness of people to believe "so many wonderful things." For Feynmann, it came down to a certain type of integrity, a "kind of care not to fool yourself", that was missing in what he called "cargo cult science".

Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can — if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong — to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, ... then you must put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it

As Kuhn described them to be, the motives of the true scientist are to gain the respect and approval of his or her peers. When technical jargon is misused, or when scientific findings are represented misleadingly, to give particular claims the superficial trappings of science for some commercial or political gain, this is easily recognised as an abuse of science [16]; it is not an abuse that is confined to popular literature however [17]

For many, at least some "pseudoscientific" beliefs, for example that the pyramids were built not by men but by prehistoric astronauts, are harmless nonsense; horoscopes are read for fun by many, but taken seriously by few. [18] The brights movement, prominently represented by Richard Dawkins, Mario Bunge, Carl Sagan and James Randi, consider that while pseudoscientific beliefs may be held for several reasons, from simple naïveté about the nature of science, to deception for financial or political gain, all such beliefs are harmful. [19]

Notes

- ↑ Magendie, F (1843) An Elementary Treatise on Human Physiology. 5th Ed. Tr. John Revere. New York, Harper, p 150; see Simpson D. (2005) Phrenology and the neurosciences: contributions of F.J. Gall and J.G. Spurzheim. ANZ J Surg.75:475-82. PMID 15943741; and Stone JL (2003) Mark Twain on phrenology Neurosurgery 53:1414-6 PMID 14633308

- ↑ Popper KR (1959) The Logic of Scientific Discovery English translation;Karl Popper Institute includes a complete bibliography 1925-1999;

- ↑ Popper KR (1962) Science, Pseudo-Science, and Falsifiability. Conjectures and Refutations; Karl Popper from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Sir Karl Popper: Science: Conjectures and Refutations

- ↑ Kuhn TS (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45808-3

- ↑ As Churchland observed, although most terms in theoretical physics have some connection with observables, they are not of the sort that would enable them to be used as operational definitions. "If a restriction in favor of operational definitions were to be followed ... most of theoretical physics would have to be dismissed as meaningless pseudoscience!" Churchland P Matter and Consciousness: A Contemporary Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind (1999) MIT Press [http://books.google.com/books?

- ↑ Peer review and the acceptance of new scientific ideas[1] (Warning 469 kB PDF)For an opposing perspective, e.g. Peer Review as Scholarly Conformity[2]

- ↑ Lakatos I (1970) "Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes" in Lakatos I, Musgrave A (eds) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, Cambridge university Press pp 91-195

- ↑ Feyerabend P (1975) Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge [3]

- ↑ McNally RJ (2003)Is the pseudoscience concept useful for clinical psychology? SRHMP Vol 2 Number 2 Fall/Winter

- ↑ Laudan L (1996) "The demise of the demarcation problem" in Ruse M But Is It Science?: The Philosophical Question in the Creation/Evolution Controversy pp 337-50

- ↑ John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) On Liberty. 1869. Chapter II: Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion

- ↑ Marcello Truzzi, On Some Unfair Practices towards Claims of the Paranormal; On Pseudo-Skepticism

- ↑ Lakatos (1977) The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Philosophical Papers Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Science and Pseudoscience - transcript and broadcast of talk by Imre Lakatos

- ↑ Thagard PR (1978) Why astrology is a pseudoscience In PSA Volume 1, edited by P.D. Asquith and I. Hacking (East Lansing: Philosophy of Science Association

- ↑ If every individual student follows the same current fashion in expressing and thinking about electrodynamics or field theory, then the variety of hypotheses being generated ... is limited. Perhaps rightly so, for possibly the chance is high that the truth lies in the fashionable direction. But, on the off-chance that it is in another direction - ... - who will find it? Richard P. Feynman Nobel Prize Lecture, 1965

- ↑ Giuffre M (1977) Science, bad science, and pseudoscience. J Perianesth Nurs 12:434-8. PMID 9464033; Ostrander GK, et al (2004) Shark cartilage, cancer and the growing threat of pseudoscience. Cancer Res 64:8485-91 PMID 15574750

- ↑ Tsai AC (2003) Conflicts between commercial and scientific interests in pharmaceutical advertising for medical journals. Int J Health Serv 33:751-68 PMID 14758858; Cooper RJ et al (2003) The quantity and quality of scientific graphs in pharmaceutical advertisements. J Gen Intern Med 18:294-7 PMID 12709097

- ↑ [The National Science Foundation stated that, in the USA, "pseudoscientific" habits and beliefs are common in the USA. http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind06/c7/c7s2.htm] National Science Board. 2006. Science and Engineering Indicators 2006 Two volumes. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation (volume 1, NSB-06-01; NSB 06-01A) Bunge (1999) stated that a 1988 survey showed that 50% of American adults rejected evolution, and 88% believed that astrology was a science.

- ↑ Beyerstein BL (1995) Distinguishing science from pseudoscience; Hewitt GC (1988) Misuses of biology in the context of the paranormal. Experientia 44:297-303 PMID 3282905; Musch J, Ehrenberg K. (2002) Probability misjudgment, cognitive ability, and belief in the paranormal. Br J Psychol 93:169-77 PMID 12031145