William Harvey

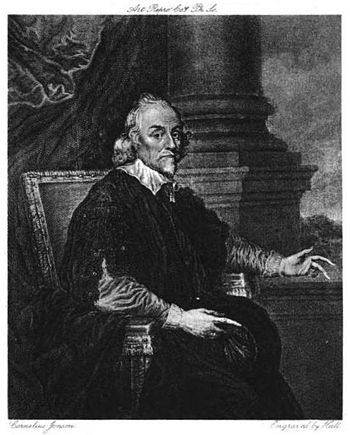

William Harvey. From book of that name by D'Arcy Power, 1897

William Harvey (1578-1657), a late 16th early 17th century English physician, gifted humanity with one of the most important contributions to the progress of medical science. By introducing quantitative methods into anatomical and physiological investigations, Harvey discovered that the heart pumps blood through the body, and does so via a system of vessels such that the blood moves in a circular path, from the heart through the arteries and back to the heart through the veins. Publishing those findings in his 1628 book, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Anatomical Exercises on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals), usually referred to as De Motu Cordis,[1] Harvey made the following contributions in the history of medical science: [2]

- He overturned the erroneous view of the roles of the heart, arteries and veins that Galen had taught — by delineating the cardinal features of the map depicting the transport path of blood through the body — that blood circulates continuously through the body from the heart and back to the heart;

- He reintroduced the concept and practice of experimentation in medical studies, earlier introduced by Galen but mostly ignored by medical researchers for nearly one and a half millennia;

- He introduced the use of quantitative methods in medical research — by estimating the volume of blood pumped by the heart each day and arguing the improbability that the body could generate that amount each day, even if it converted to blood everything ingested each day; and,

- Independently of his contemporary, Francis Bacon, he showed that reasoning by induction — generalizing from a collection of separate but related facts — could yield valid inferences about human physiology.

|

"Since all things, both argument and ocular demonstration, show that the blood passes through the lungs, and heart by the force of the ventricles, and is sent for distribution to all parts of the body, where it makes its way into the veins and porosities of the flesh, and then flows by the veins from the circumference on every side to the centre, from the lesser to the greater veins, and is by them finally discharged into the vena cava and right auricle of the heart, and this in such a quantity or in such a flux and reflux thither by the arteries, hither by the veins, as cannot possibly be supplied by the ingesta, and is much greater than can be required for mere purposes of nutrition; it is absolutely necessary to conclude that the blood in the animal body is impelled in a circle, and is in a state of ceaseless motion; that this is the act or function which the heart performs by means of its pulse; and that it is the sole and only end of the motion and contraction of the heart." De Motu Cordis Chapter XIV: Conclusion of the Demonstration of the Circulation |

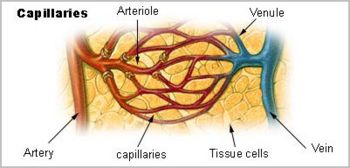

In his dissections of humans and animals, Harvey could not see vessels connecting the arteries to the veins. He could only infer that a connecting pathway existed. In 1661, a few years after Harvey died, the Italian biologist, Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), using an early microscope, discovered capillaries, tiny blood vessels not visible to the naked eye, connecting arteries to veins. Seemingly fittingly, Malpighi entered the world the same year Harvey published De Motu Cordis.

Among them, Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), William Harvey (1578-1657), and Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), in works published in little more than a century, from 1543 to 1661, demonstrated central truths of human anatomy and physiology that had escaped Western medicine for more than a millenium following the erroneous teachings of Galen (130-216 C.E.). It required three investigators to break the stranglehold of one.

Brief sketch of Williams Harvey’s life

Born in 1578 (April 1, at Folkstone, on the east coast of Kent, England), the eldest of seven brothers, William Harvey entered the world shortly after Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) had died, though Vesalius's reputation based on his remarkably detailed and elegantly drawn illustrations revolutionizing the understanding of human anatomy had not. William Harvey had giant shoulders to stand on, and ultimately he saw further.

Harvey received his early education in the classics, in Canterbury, at King's School, there "....admonished to speak Greek or Latin even on the playground".[3] Harvey's father, a landowner and successful merchant, could afford to send Harvey to the University of Cambridge, which he entered at age 16 years and received his B.A. at age 19 years. Harvey developed an interest in medicine and decided to go Italy, one of the major centers of intellectual activity in Europe at the time. He enrolled in the then renown University of Padua, studying medicine under Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente, a noted anatomist in the Vesalian tradition, who had discovered the valves in the veins, a discovery which later contributed to Harvey's thinking that led to his discovery of the blood circulatory system. Harvey received his Doctor of Medicine degree in April, 1602, at age 24 years.

After Padua, Harvey returned to England and developed a practice in medicine, married, and became a Fellow of the College of Physicians in London. He also secured a position as physician at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, one of London’s great hospitals, and there and in his private practice distinguished himself as a physician. In 1615, at age 37 years, the College of Physicians elected him their Professor of Anatomy and Surgery, and gave him the honor of the Lumleian Lectureship, a lifetime remunerated position, in which he lectured on human anatomy, physiology and surgery, including performing demonstration dissections, officially twice per week, from 1616 to 1656, the year before he died. The lecturership gave Harvey a great opportunity to organize his thinking and guide his research.

In 1618 he became physician extraordinary to the king (James I), and ministered to many eminent aristocrats, including Francis Bacon, for whom he had little regard as an intellectual. After Charles I succeeded the throne, in 1625, Harvey became Charles' physician, benefitting from the King’s patronage to pursue his medical investigations. When civil strife engulfed England, Harvey, now in his 60s retired to live with a brother, pursuing his experiments until he died in 1657, having lived nearly to the age of 80 years.[4] [5]

De Motu Cordis

To read the full-test of De Motu Cordis in English translation, click on the "Works" tab in the banner at the beginning of this page. Equivalently, click De Motus Cordis, which brings you to same subpage of this article.

References cited and notes

- ↑ Harvey W. (1628) On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals. Translation: Robert Willis. The Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall, halsall@fordham.edu, Sourcebook Compiler.

- ↑ Nuland SB. (2008) Doctors: The History of Scientific Medicine Revealed Through Biography. The Teaching Company. (12 lectures, 30 minutes/lecture), Course No. 8128.

- ↑ Adler RE. (2004) Medical Firsts: From Hippocrates to the Human Genome. Hoboken NJ: Wiley.

- ↑ Huxley TH. (1878) William Harvey and the Discovery of the Circulation of the Blood. (A free full-text PDF download) A Lecture delivered in the Free Trade Hall, November 2nd, 1878. From the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation [Etext #2939].

- ↑ William Harvey (1578-1657). Originally appearing in Volume V13, Page 47 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.