Mission San Diego de Alcalá

| This article is part of a series on the Spanish missions in California  Mission San Diego de Alcalá, circa 1899.[1] | |

| HISTORY | |

|---|---|

| Location: | San Diego, California |

| Coordinates: | 32° 47′ 4″ N, 117° 6′ 23″ W |

| Name as Founded: | La Misión San Diego de Alcalá [2] |

| English Translation: | The Mission of Saint Didacus of Alcalá [3] |

| Patron Saint: | Saint Didacus of Alcalá de Henares, Spain [2] |

| Nickname(s): | "Mother of the Alta California Missions" [4] |

| Founding Date: | July 16, 1769 [5] |

| Founded By: | Father Presidente Junípero Serra [6] |

| Founding Order: | First [3] |

| Headquarters of the Alta California Mission System: | 1769–1771 [7] |

| Military District: | First [8][9] |

| Native Tribe(s): Spanish Name(s): |

Kumeyaay (Ipai / Tipai) [5] Diegueño [5] |

| Primordial Place Name(s): | Kosoi, Nipawai [10] (also Nipaguay [11]) |

| SPIRITUAL RESULTS | |

| Baptisms: | 6,522 [12] |

| Confirmations: | 1,379 [13] |

| Marriages: | 1,794 [12] |

| Burials: | 4,322 [12] |

| Year of Neophyte Population Peak: | 1824 [14][15] |

| Neophyte Population: | 1,455 [14][15] |

| Neophyte Population in 1832: | 1,828 [14][15] |

| DISPOSITION | |

| Secularized: | 1834 [3] |

| Returned to the Church: | 1862 [3] |

| Caretaker: | Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego |

| Current Use: | Parish Church |

| National Historic Landmark: | #NPS–70000144 |

| Date added to the NRHP: | April 15, 1970 [16] |

| California Historical Landmark: | #242 |

| Web Site: | http://missionsandiego.com |

Mission San Diego de Alcalá is a former religious outpost established by Spanish colonists on the west coast of North America in the present-day State of California. Founded on July 16, 1769 by Roman Catholics of the Franciscan Order, the settlement was the first in the twenty-one mission Alta California chain, and is therefore known today as "California's First Church." Named after a lay brother of the Order of Friars Minor who died at Alcalá de Henares, Spain in 1463, Mission San Diego was the site of the first Christian burial in Alta California, and of the region's first public execution. Father Luís Jayme, "California's First Christian Martyr," lies entombed beneath the chancel floor. Designated as a historic landmark at both the state and national levels, in 1976 Pope Paul VI named the Mission as a Minor Basilica. Today the chapel serves as a parish church within the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego.

History

Precontact and early contact

The former Spanish settlement at Nipawai lies within that area occupied during the late Paleoindian period and continuing on into the present day by the Native American society commonly known as the Diegueño;[17] the name denotes those people who were ministered by the padres at Mission San Diego de Alcalá.[18] Relatively much is known about the native inhabitants in recent centuries, thanks in part to the efforts of the Spanish explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who documented his observations of life in the coastal villages he encountered along the Southern California coast in October of 1542.[19] Cabrillo, a Portuguese navigator in the service of Spain, is credited with the "discovery" of San Diego Bay. On the evening of September 28, 1542 the ships San Salvador and Victoria sailed into the harbor, whereupon Cabrillo christened it "San Miguel." [20] During that expedition a landing party went ashore and briefly interacted with a small group of natives. Some sixty years later another Spanish explorer, Sebastián Vizcaíno, made landfall some ten miles from the present Mission site. Under Vizcaíno's command the San Diego, Santo Tomás, and frigate Tres Reyes dropped anchor on November 10, 1602, and the port was renamed "San Diego de Alcalá." [21][22]

It would be another 167 years before the Spanish returned to San Diego. Ever since the voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert the pagans in Nueva España ("New Spain") to Roman Catholicism in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. However, it was not until 1741—the time of the Vitus Bering expedition, when the territorial ambitions of Tsarist Russia towards North America became known—that King Philip V felt such installations were necessary in Upper California.[23] Finally in 1769 Visitador General José de Gálvez sent the expedition of Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà to found a mission at San Diego and presidio at Monterey, respectively, thereby securing Spain's claim to the entire Pacific Coast by right of doscovery.[24] Two groups traveled from Lower California on foot, while a pair of packet ships (bearing supplies) traveled up the coast from the Baja Peninsula.[25][26]

Mission Period (1769 – 1833)

The first expedition to reach San Diego came by sea aboard the packet ship San Antonio, commanded by Captain Juan Pérez, which sailed into port on April 11 and dropped anchor near Point Guijarros.[27] Under the command of Captain Vicente Vila, the San Carlos (formerly the Golden Fleece), despite having put to sea well ahead of her sister ship, nonetheless did not arrive in San Diego until the afternoon of April 29, severe storms having hampered her progress. The first overland expedition, under Captain Fernando Rivera y Moncada, completed their journey on the afternoon of May 4, while Governor Portolà's contingent arrived on June 29.[28] Many members of the overland expeditions fell ill along the way, and a majority of the crews from both ships contracted scurvy during their voyages; in all, over a hundred men (including the crew of a third ship, the San José which went down en route) died.[5] Portolà and the "Sacred Expedition" continued on to Monterey Bay on July 14, and just two days later, on July 16, a cross was raised and Father Serra held the first Holy Mass; Mission San Diego de Alcalá was officially founded.[2] The padres' initial efforts to establish an outpost at the San Diego met with little success. The Mission was originally founded at a site overlooking the Bay known today as "Presidio Hill" (Kosoi to the natives), but the natives resented the Spaniards' intrusion, and the settlement was attacked within a month.[29][30] By the first few months of 1770, food had run low, no permanent buildings were erected, and there had yet to be a single conversion. Four soldiers, eight Catalonian volunteers, one servant, and six Christian Indians from Lower California had died from scurvy since the expedition's arrival; serious consideration was therefore given to abandoning the site and returning to the Baja settlements. It was therefore determined that, if a supply ship did not arrive by March 19 (Saint Joseph's Day), the expedition would be recalled.[31] Father-Presidente Serra, in response, wrote a lengthy letter addressed to Father Francisco Palóu the following day:

Four Fathers, Fr. Juan Crespí, Fr. Fernando Parrón, Fr. Francisco Gómez, and I, are here, ready to found a second mission, if the ships arrive. Should we see that hope and supplies are vanishing, I shall remain here alone with Fr. Juan Crespí and hold out to the very last. May God give us His holy grace. Recommend us to God that so it may be...[32]

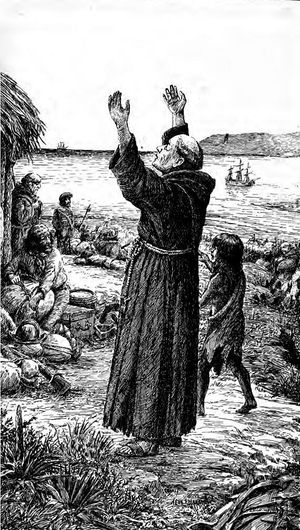

The Ship! The Ship! California is saved! Father Serra rejoices at the sight of the packet ship San Antonio entering San Diego Bay on March 19, 1770 with desperately-needed food and supplies. The San Carlos rests at anchor just offshore.[33]

Serra feared that if San Diego were abandoned, "..centuries might come and go before the country would again be revisited...;" finally, just before sunset on the 19th, the San Antonio entered the harbor.[34] The ship had been bound for Monterey to deliver supplies to the expedition waiting there, but had lost one of its anchors and was forced to make port in San Diego, where a spare anchor from the San Carlos could be retrieved.[34] With the settlement now properly putfitted with supplies, the missionaries set about constructing permanent buildings at Kosoi, in 1773 the site of California's first Christian burial.[35] The Mission was relocated to its present location (the native village of Nipawai) in August of 1774.[36] The lack of a dependable water supply, coupled with the proximity of the military personnel at the presidio, led Father Luís Jayme to seek permission to relocate the mission from its original site, to the valley some six miles upriver to the east, where it remains today. Almost immediately there was a noticeable increase in the number of baptisms, which in 1775 totaled 431 (compared to 274 for the preceding four years combined).[37]

Native resistance continued almost unabated.[38] At approximately 1:30 a.m., on the moonlit night of November 4, 1775 between 600 and 800 warriors from the surrounding rancherías silently crept into the Mission compound. After plundering the chapel, they set the other buildings ablaze. The commotion soon awakened the two missionaries, the Spanish guards, and the Christian neophytes. Fray Jayme (who had been left behind to run the Mission while Father Serra moved on to found other missions) was killed in the melee, thereby making him California's first Christian martyr.[39] The Mission buildings were reduced to ashes, and all records and manuscripts lost in the blaze; the censer, the chalice used at Holy mass, and the pieces of coin used during marriage ceremonies were "melted into a solid mass." [40] Although resentment over various abuses had likely built up over a period of time, the recent infliction of corporal punishment by the missionaries apparently instigated the attack.[41] A contingent of soldiers was subsequently sent out to capture those responsible.

The following February, one of the neophytes who had participated in the assault repented and sought refuge in the jacal then being used for Divine service. Captain Rivera refused to recognize the native's claim of sanctuary, reasoning that "...the [place] where Holy mass was celebrated was not a church but a warehouse." [42] Though threatened with excommunication, Rivera remained determined to remove the Indian (by force if necessary) and did so personally on March 26, 1776. Seeking to have his excommunication lifted, traveled to Monterey to bring the matter directly before Father Presidente Serra. After hearing the captain's arguments and reviewing several letters sent by the Mission fathers regarding the incident, Serra decided that Rivera was to return the prisoner to the church in San Diego, and that Fathers Font and Fustér would thereupon lift the excommunication.[43]

San Diego achieved the reputation early on as site of the region's first public execution, one it may not deserve. On April 6, 1778 four native chiefs of Pámo, one of San Diego's Indian villages, were convicted of conspiring to kill Christians and were sentenced to death by José Francisco Ortega, Commandant of the Presidio of San Diego; the four were to be shot on April 11.[44] However, there is some doubt as to whether or not the executions actually took place.[45]

José María de Echeandía, the first native Mexican to be elected Governor of Alta California, issued his "Proclamation of Emancipation" (or "Prevenciónes de Emancipacion") on July 25, 1826.[46] All Indians within the military districts of San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Monterey who were found qualified were freed from missionary rule and made eligible to become Mexican citizens; those who wished to remain under mission tutelage were exempted from most forms of corporal punishment.[47] Catholic historian Zephyrin Engelhardt referred to Echeandía as "...an avowed enemy of the religious orders." [48] Although Governor José Figueroa (who took office in 1833) initially attempted to keep the mission system intact, the Mexican Congress nevertheless passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833.[49] The Act also provided for the colonization of both Alta and Baja California, the expenses of this latter move to be borne by the proceeds gained from the sale of the mission property to private interests.

Rancho Period (1834 – 1849)

On August 9, 1834 Governor Figueroa issued his "Decree of Confiscation." [50] The missions were offered for sale to citizens, who were unable to come up with the price, so all mission property was broken up into ranchos and given to ex-military officers who had fought in Mexico's war against Spain. On June 8, 1846 Mission San Diego de Alcalá was given to Santiago Arguello by Governor Pío Pico "...for services rendered to the government." [51] Upon execution of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (which ended the Mexican–American War in 1848) the Mexican territory of Alta California became a United States territory, joining the Union in 1850.

California Statehood (1850 – 1900)

An illustration depicts the brutal death of Father Luís Jayme at the hands of angry natives at Mission San Diego de Alcalá, November 4, 1775.[52] A carpenter named Urselino and José Romero, a blacksmith, were also killed during the attack.[51] The uprising was the first of a dozen similar incidents that took place in Alta California during the Mission Period.[53][54]

Beginning in November, 1853 and continuing through late 1858 or early 1859, various companies of artillery and cavalry were housed at the Mission complex. During the occupation the soldiers effected a number of repairs and added a second floor to the chapel building. President Abraham Lincoln signed a proclamation on May 23, 1862 that restored ownership of the Mission proper to the Roman Catholic Church.[51][55] When Mission San Diego de Alcalá was granted back to the Church, it was in ruins. In the 1880s Father Anthony Ubach began to restore the old Mission buildings.

20th century and beyond (1901 – present)

Father Ubach died in 1907 and restoration work ceased until 1931. In 1941, the Mission once again became a parish church, in what is still an active parish serving the Diocese of San Diego. In 1976, Pope Paul VI designated the Mission church as a minor basilica.

Legacy

Other designations

- California Historical Landmark #52 — mission dam and flume system completed in 1816

- California Historical Landmark #784 — El Camino Real (starting point in Alta California)

- City of San Diego Historic Designation #113

Mission industries

Wheat, corn, wine grapes, barley, and beans were the major crops grown at San Diego; cattle, horses, and sheep were raised as well. In 1795, construction on a system of aqueducts was begun to bring water to the fields and the Mission (the the first irrigation project in Upper California). Supervising the work was Fray Pedro Panto, who was poisoned by his Indian cook Nazario before the project was completed.[56]

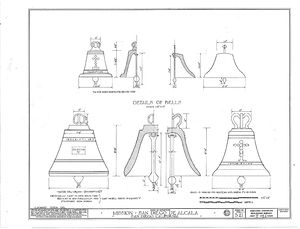

Mission bells

Bells were vitally important to daily life at any mission. The bells were rung at mealtimes, to call the Mission residents to work and to religious services, during births and funerals, to signal the approach of a ship or returning missionary, and at other times; novices were instructed in the intricate rituals associated with the ringing the mission bells. The largest, and sole original bell hanging in Mission San Diego's 46-foot-high campanario, or "bell wall," is the Mater Del Orosa. Weighing in at some 1,200 pounds (544 kilograms), the bell was originally cast in New Spain in 1796, then recast in San Diego in 1894 from the remnants of the other four original bells.[57] The slightly smaller adjacent bell was cast in 1802 and bears the inscription S~IVAN~MUCENO~AVE~MARIA~PURISIMA. It is the only bell to feature a "conan" (crown). The middle pair of bells are essentially identical, and were cast in 1789. One bell is inscribed SA~NTA~MARI~ANDALENA~ANO~DE~1789.

The crown bell is rung daily at noon and at six p.m., and before Sunday Mass. All five bells are rung in unison only on the anniversary of the Mission's founding as part of the annual "Festival of the Bells."

Notes and references

- ↑ (PD) Painting: Edwin Deakin

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Leffingwell, p. 17

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Krell, p. 71

- ↑ Young, p. 14

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Yenne, p. 24

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 196

- ↑ Yenne, p. 186

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. v, 228: "The military district of San Diego embraced the Missions of San Diego, San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, and San Gabriel..."

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 195

- ↑ Bancroft, P. 220

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Krell, p. 315: as of December 31, 1832; information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 300-301: as of December 31, 1832. An additional 426 confirmations were performed between January 1, 1833 and December 31, 1841.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 Krell, p. 315: Information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Engelhardt 1920, pp. 300-301: The smallest recorded neophyte population (97) was seen in 1774.

- ↑ San Diego Mission Church

- ↑ Kroeber 1925, p. 883: Kroeber estimated that the native population in the immediate vicinity of San Diego was approximately 3,000 in 1770 (exclusive of those in Baja California).

- ↑ As with other Spanish names given to the indigenous tribes they encountered, the appellation Diegueño does not necessarily identify a specific ethnic or tribal group.

- ↑ Yenne, p. 8

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 3: September 28 was the eve of the "Feast of the Archangel Saint Michael."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 6-9: November 10 was the eve of "St. Martin's Day."

- ↑ Davidson, p. 2: "Sebastian Vizcaino, entering Nov. 11-12, 1602, first applied the name San Diego de Alcalá to this port."

- ↑ Morrison, p. 214

- ↑ Yenne, p. 10

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 9

- ↑ Yenne, p. 10: In January, 1769 the San Carlos departed Baya de San Barnabé in La Paz, followed a month later by the San Antonio, which sailed out of Cabo San Lucas. A third vessel, the San José, left New Spain later that spring but was lost at sea.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 9-10: "Ballast Point" is also the likely spot of Cabrillo's anchorage.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 13, 17: Father Serra arrived with the second expedition's main body on July 1, forty-six days after having left Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá.

- ↑ Young, p. 12

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 12: Not all of the native cultures responded with hostility to the Spaniards' presence.

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 32: On February 7, Pedro Fages and Engineer Miguel Costansó wrote to Viceroy José de Gálvez that "..they [the troops remaining] could hold this Port until the arrival of one of the packetboats San José or the Principe (San Antonio) which we are expecting daily"—"podrá conservar este Puerto hasta la venida de uno los pacbotes El San José ó El Principe (San Antonio) que esperamos de dia á otro."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 33

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 35-37

- ↑ Jump up to: 34.0 34.1 Engelhardt 1920, p. 36

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 196

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 7

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 300

- ↑ "Tipai-Ipai" by Katharine Luomala pp. 592-609 in Volume 8, "California" in the Handbook of North American Indians: "Of all the mission tribes in the Californias, Tipais and Ipais most stubbornly and violently resisted Franciscan or Dominican control."

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 11

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 71

- ↑ Archibald: "Open revolt is, of course, the most obvious reaction to real or imagined oppression."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 72-73: Father Font acknowledged that "...the church is a jacal of tule, which is very poorly constructed and had formerly been used as a warehouse." Rivera issued an "official note" to Father Vicente Fustér stating that "...the Indian should be turned over within so many hours; if this was not done, he [Rivera] would take him out by force and bring him to the guardhouse as a prisoner."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p.76: It is not known whether or not Rivera complied with Serra's direction in this regard.

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 196; Bancroft, vol. i., p. 316

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 96-97: Reference is made to three letters written by Father Serra to Father Lasuén dated April 22 and June 10, 1778 and September 28, 1779 wherein Father Serra expresses his satisfaction over Governor Felipe de Neve's apparent grants of clemency in this regard. Based on these writings, Engelhardt concludes "It would seem that the sentence of death was commuted. At any rate, there are no particulars as to an execution."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 80

- ↑ Bancroft, vol. i, pp. 100-101: Bancroft postulated that the motives behind the issuance of Echeandía's premature decree had more to do with the his desire to appease "...some prominent Californians who had already had their eyes on the mission lands..." than they did with concerns regarding the welfare of the natives.

- ↑ Stern and Miller, pp. 51-52

- ↑ Yenne, p. 19

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 114

- ↑ Jump up to: 51.0 51.1 51.2 Leffingwell, p. 19

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 12

- ↑ Paddison, p. 48

- ↑ Chapman 1921, pp. 310-311: Chapman notes that "Latter-day historians have been altogether too prone to regard the hostility to the Spaniards on the part of the California Indians as a matter of small consequence, since no disaster in fact ever happened...On the other hand the San Diego plot involved untold thousands of Indians, being virtually a national uprising, and owing to the distance from New Spain to and the extreme difficulty of maintaining communications a victory for the Indians would have ended Spanish settlement in Alta California." As it turned out, "...the position of the Spaniards was strengthened by the San Diego outbreak, for the Indians felt from that time forth that it was impossible to throw out their conquerors." See also Mission Puerto de Purísima Concepción and Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer regarding the Yuma massacres of 1781.

- ↑ Robinson, pp. 31-32: Patents for each mission were issued to Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany based on his claim filed with the Public Land Commission on February 19, 1853.

- ↑ Smythe, p. 77

- ↑ Krell, p. 78