Gunpowder

Gunpowder is a propellant used in firearms, fireworks, and rocket motors. Gunpowder is a low explosive – it burns rapidly without outside air, and in a confined space, will build up enough pressure to cause an explosion. While black gunpowder and even smokeless powder have been used for commercial mining and earthmoving, since their low detonation velocity still has substantial explosive power, they have largely been replaced by more appropriate explosives. While smokeless powder may contain nitroglycerin or nitrocellulose, those ingredients are formulated differently when a high explosive effect is desired.

History

There are two broad classes of gunpowder, black and smokeless powder. Smokeless powder — a relative term, as it produces some smoke but not dense clouds — has replaced black powder for almost all applications not involving historical reenactment. Modern smokeless powders, of various formulations, are both safer and more powerful than black powder.

Black powder

Black gunpowder was first developed in China, no later than the eleventh century A.D., and possibly earlier. (Early texts are not clear if the mixture described is true gunpowder or not.) It was introduced into Europe in the thirteenth century, through unknown routes. The earliest known description of a true gunpowder formula is in a letter from Francis Bacon to Pope Clement IV in 1267 A.D. By 1275, Albertus Magnus described a formula of four parts saltpeter (potassium nitrate) to one part charcoal (material) and one part sulfur; the chemically ideal proportions are closer to 75% saltpeter, 11.5% sulfur, and 13.5% charcoal.

The earliest European was a finely ground mixture of charcoal, potassium nitrate, and sulfur. This mixture, known as "serpentine powder," tended to absorb moisture, to separate into its components while being transported, and did not burn if packed too tightly into a gun. It gave way, in the 15th century, to corned powder which was pressed into pellets and screened to a uniform size.

Even with better mechanical formulation, black powder is extremely sensitive to friction and heat, and, while having less explosive power when confined, is far more dangerous to handle than smokeless powder. Aside from its use in historical applications, it still has applications as part of the initiating system of artillery shells.

Smokeless powder

Black powder has gradually been superseded by other propellants which provide higher energy density, lack of smoke, or other desirable properties. In the mid-19th century chemists realized that black-powder smoke wasted fuel, reducing muzzle velocity, while a smokeless powder converted all its fuel, allowing for increased velocity of projectiles. Increased velocity was necessary for rapid-fire shells and in battle against ironclad vessels. In 1884, Frenchman Paul Vieille invented smokeless gunpowder.

Modern smokeless powders are of three basic types:

- single-base propellant: Nitrocellulose and inert ingredients for mechanical properties

- double-base propellant: Nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin or other plasticizer of nitrocellulose, and inert ingredients for mechanical properties

- triple-base propellant: Nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin or equivalent, nitroguanidine, and inert ingredients for mechanical properties

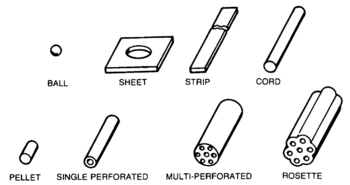

After mixing the ingredients, smokeless powder is a plastic material that can be cast, extruded, or otherwise made into specific grain shapes and sizes. An actual propellant filling may have a mixture of grain shapes of different propellant types.

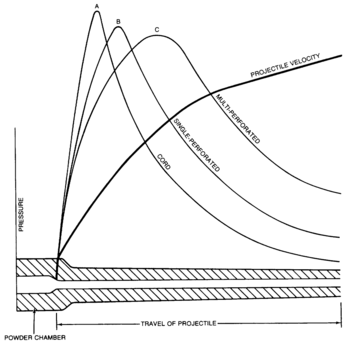

- Progressive grains, exemplified by rosettes and multiperforated types, increase the exposed area as they burn, increasing pressure over time

- Neutral grains, such as the perforated forms, expose a constant area

- Digressive grains, represented by cords, decrease the exposed area as they burn, thus decreasing pressure over time

"Grain geometry and burning rate are interrelated. The burning time of a propelling charge that contains a propellant with a high burning rate and strongly digressive grain geometry could be equal to the burning time of a charge that contains a propellant with a low burning rate and strongly progressive grain geometry." Short burning times are necessary in short-barreled firearms, which have only a limited time to transfer energy to the projectile. Short burning times with high instantaneous pressures, however, put greater stress on the metal barrel.

"European nations have favored the use of single perforation, strip, and cord propellants. The United States uses single perforation and multiperforation propellants. The single perforation grains may be slotted or unslotted. The slotted grain has the desirable characteristic of venting gas during combustion. All countries use ball propellants for small arms."[1] These affect the burning time and the shape of the pressure-versus-time curve.

Burning time is related to the detonation velocity (or deflagration velocity) of the material, and the total surface area of propellant exposed. Grain shape affects the area exposed. Complex shapes allow control of the development of pressure.

Civilian uses

A basic use of gunpowder was in hunting and sport firearms, regarded as tools in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the U.S., for example, E.I. du Pont started a gunpowder factory in Delaware in 1802, "at the urging of Thomas Jefferson, who advised him of the new American nation’s need of a domestic supply of high-quality gunpowder. Jefferson gave DuPont his first order, for the refining of some saltpeter (an ingredient in black powder)."[2]

Miners began using gunpowder for excavation when Caspar Weindel invented the technique of packing manually driven drill holes with powder. Drill technique paced the utility of the method, but black powder was inherently limited and was replaced by dynamite. One of the limitations of black powder was its slow detonation velocity, so unless the drill holes were carefully sealed, much of the gas would escape. [3]

Military uses

Gunpowder was used as a propellant for rockets, and to propel shot in cannon. During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, Chinese gunpowder technology spread to the whole of Southeast Asia via both the overland and maritime routes, long before the arrival of European firearms. The impact of Chinese firearms on northern mainland Southeast Asia in terms of warfare and territorial expansion was profound.

Technological developments of guns themselves affected the desired characteristics of propellants; advances in propellants allowed developments of new gunnery technologies. Until the 19th century, gunnery was at short range, which allowed short, unrifled barrels. Scientific study of gunnery began with exterior ballistics, or the behavior of projectiles in flight, but, in the 19th century, began to explore interior ballistics, or the behavior of projectiles in the gun.

Carl Bomford, a U.S. Army lieutenant colonel who was Chief of Ordnance, created an apparatus to measure the pressure vs. time in a gun barrel. He drilled holes at equal distances along the cannon barrel, to which pistol barrels, loaded with a bullet, were attached. When the cannon was fired, the pressure wave propelled the bullets down the barrels, where they struck devices called ballistic pendulums. The pendulum's movement was proportional to pressure. Bomford confirmed that pressure, at that time, was greatest at the breech, and, based on his pressure curves, gun barrels, in 1844, started to be designed of varying thickness.

In 1847, the "Father of Naval Ordnance", a U.S. Navy lieutenant, examined naval requirements, and decided that to meet tactical requirements, larger shells, which could be driven with higher pressure, were necessary. His 1847 design for a 9-inch cannon adopted a "bottle shape" for the barrel, using the least weight for the predicted pressures. Continuing his research, he concluded that the largest shell that could be handled by the manual means in use would weigh 135 pounds, which he designed as an 11-inch projectile. The Navy resisted his 11-inch design, but ordered a number of 9-inchers in 1854. [4]

Naval warfare began to push improvements, including rifled, higher-velocity, longer-range cannon to overcome "ironclad" armor. As indirect fire became practical, first on land and then at sea, there was greater demand for longer barrels, which needed both higher-pressure, and later controlled-pressure, propellants.

Changes in composition were also experimented with, and in the 1880s brown powder made from under-burnt charcoal was adopted as one means of decreasing the burning rate. A serious drawback of these gunpowders was that only about half of the mixture was converted into gas, the remainder becoming a dense smoke. The French in 1886 adopted smokeless powder made of nitrocellulose (gun-cotton). Four years later, the Royal Navy began using smokeless powder made from a nitroglycerine base. Both these compounds liberated four to five times as much energy as did the black powder used earlier. In addition, these materials could be formed readily into grains so shaped as to control the rate of burning. This gave a uniform pressure, permitting a higher projectile velocity without straining the gun.

Smoke and flash both were undesirable. Smoke obscured targets and made aiming difficult. While smokeless powder is not free of smoke, it produces much less than black powder.

Flash, more an issue with smokeless powder, created multiple problems. In night fighting, it dazzled gun crews. Especially at night, but to some extent against large cannon in the daytime, counterbattery fire could identify firing positions to be targeted, using techniques developed by the Canadian Army in the First World War.

Black powder still continued in use as a burster charge for projectiles until just before World War I, when more powerful and less sensitive explosives were adopted.

Land warfare

Sieges were the primary form of warfare in the Middle Ages in Europe. During the period 1346-1500 cannon complemented catapults in siege warfare; only after 1480 did technical improvements in gunpowder and metallurgy render catapults obsolete. Cannons shooting lead, iron or stone projectiles could knock down a castle's high walls, hence the castle had to be abandoned.

Indirect fire began to be established practice in the late 19th Century, calling for longer barrels with increased caliber.

Few technological developments in the history of warfare have been as portentous as the appearance around the turn of the 16th century of effective heavy gunpowder ordnance on shipboard, which began a new era in sea warfare. Employed on Mediterranean war galleys and Portuguese caravels, the weapons marked the solution of a series of daunting technological problems, beginning with the appearance of gunpowder in Europe about 1300. Unlike developments on land, change was at first gradual, but shortly after 1400 the pace of development sharply accelerated to culminate in what may legitimately be termed a revolution in firepower at sea.[5]

At the close of the 19th century, the U.S. Navy followed the lead of the French and adopted a nitrocellulose powder as a propellant charge. This proved reasonably satisfactory until World War II night engagements, when smokeless powder was objectionable because its flash temporarily blinded the ships' crews, as well as giving away the location of the gun and the ship mounting it.

Various flash suppressors were devised and mixed with the powder, which was formed into grains for small guns and into pellets for the larger guns. The British used a multiple-based powder, Cordite N, which was relatively flash-free, but which the U.S. Navy considered to be brittle, unduly sensitive to shock, and hazardous in hot climates. As a result the United States developed other flashless powders and was placing one of them, Albanite, in large scale production at the end of World War II. Triple-base propellants are especially flameless.

By the Second World War, gunpowder was no longer used as a shell or bomb main charge.

References

- ↑ Military Explosives, U.S. Department of the Army, September 1984, TM 9-1300-214, pp. 9-5 to 9-11}}

- ↑ History of DuPont & the Government, DuPont

- ↑ Halbers Powell Gillette (1904), Rock excavation: methods and cost, M.C. Clark, pp. 106-108

- ↑ Carl D. Park (2007), Ironclad down: the USS Merrimack-CSS Virginia from construction to destruction, Naval Institute Press, pp. 112-114

- ↑ Guilmartin, "The Earliest Shipboard Gunpowder Ordnance" (2007)