Edwin Meese: Difference between revisions

(Adding more detail about his time in the Reagan administration) |

(Adding section about his early life, sourced from Wikipedia) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Meese served as a counselor to Reagan, and sat on both his cabinet and the [[National Security Council]], from 1981 to 1985. Meese played a leadership role in the development of Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative. | Meese served as a counselor to Reagan, and sat on both his cabinet and the [[National Security Council]], from 1981 to 1985. Meese played a leadership role in the development of Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative. | ||

==Young life== | |||

Meese was born on December 2, 1931, in Oakland, California, the eldest of four sons born to Leone (née Feldman) and Edwin Meese, Jr. He was raised in a practicing Lutheran family, of German descent. His father was an Oakland city government official, president of the Zion Lutheran Church, and served 24 years in the non-partisan office of Treasurer of Alameda County. | |||

At age 10, Meese published along with his brothers a mimeographed neighborhood newspaper, the ''Weekly Herald'', and used the proceeds to buy a war bond. The young Meese also had a paper route and worked in a drugstore. At Oakland High School, Meese was involved in the Junior State of America and led his high school debate team to statewide championships. He was valedictorian of Oakland High School's class of 1949. | |||

Two weeks prior to graduation, Meese was accepted to Yale University and granted a scholarship. At Yale, Meese served as president of the Yale Political Union, chairman of the Conservative Party, chairman of the Yale Debate Association, and a member of the secret society Spade and Grave. Meese made the dean's list, and graduated with a B.A. in political science in 1953. | |||

==Reagan Administration Attorney General== | ==Reagan Administration Attorney General== | ||

Reagan appointed Meese the successor to [[U.S. Attorney General]] | Reagan appointed Meese the successor to [[U.S. Attorney General]] William French Smith when he began his second term.<ref name=Cq/><ref name=nytimes1984-12-19/> Senate confirmation of his appointment was contentious. Archibald Cox, on behalf of the lobby group Common Cause, alleged the record showed Meese had shown favoritism to financial backers, enabling them to subsequently assume positions in the first Reagan administration. The Senate confirmed his appointment by a vote of 63–31 on February 24, 1985.<ref name=nytimes1985-02-24/> | ||

On May 21, 1984, Reagan had announced his intention to appoint the Attorney General to study the effect of pornography on society. The Meese Report, officially the ''Final Report of the Attorney General's Commission on Pornography'', convened in the spring of 1985 and published its findings in July 1986. The Meese Report advised that pornography was in varying degrees harmful. Following its release, guidelines of the Department of Justice were modified to enable the government to file multiple cases in various jurisdictions at the same time, which eroded some of the markets for pornography. | On May 21, 1984, Reagan had announced his intention to appoint the Attorney General to study the effect of pornography on society. The Meese Report, officially the ''Final Report of the Attorney General's Commission on Pornography'', convened in the spring of 1985 and published its findings in July 1986. The Meese Report advised that pornography was in varying degrees harmful. Following its release, guidelines of the Department of Justice were modified to enable the government to file multiple cases in various jurisdictions at the same time, which eroded some of the markets for pornography. | ||

In 1989 testified before Congress that he had been concerned that [[Efforts to impeach Ronald Reagan|Reagan might face impeachment]] over the | In 1989 testified before Congress that he had been concerned that [[Efforts to impeach Ronald Reagan|Reagan might face impeachment]] over the Iran-Contra affair.<ref name=nytimes1987-03-06/> | ||

In March of 1989, Meese was called as a witness, by the prosecution, in the trial of former Reagan aide [[Oliver North]].<ref name=nytimes1989-03-29/> North was on trial for the illegal shredding of documents, and Meese confirmed the fears within the senior elements of the Reagan administration that Reagan was at risk of being impeached.<ref name=nytimes1991-05-30/> | In March of 1989, Meese was called as a witness, by the prosecution, in the trial of former Reagan aide [[Oliver North]].<ref name=nytimes1989-03-29/> North was on trial for the illegal shredding of documents, and Meese confirmed the fears within the senior elements of the Reagan administration that Reagan was at risk of being impeached.<ref name=nytimes1991-05-30/> | ||

==Attribution== | |||

{{WPAttribution}} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 07:19, 6 August 2024

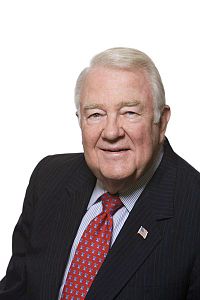

| Edwin Meese | |

|---|---|

| |

| Occupation | politician |

| Known for | played a role in trading arms for hostages in the Iran-Contra scandal |

Edwin Meese (b. 1931) is an American politician who served as U.S. Attorney General in the second Reagan Administration (1985-1989). He is a member of the Republican Party and on the Board of Directors of the Federalist Society.

He worked under California Governor Ronald Reagan, from 1967 to 1974, in various senior positions, including as his chief of staff.[1] In 1980 Meese joined the Reagan Presidential Campaign, again as chief of staff. Meese headed Reagan's transition team.[2]

Meese served as a counselor to Reagan, and sat on both his cabinet and the National Security Council, from 1981 to 1985. Meese played a leadership role in the development of Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative.

Young life

Meese was born on December 2, 1931, in Oakland, California, the eldest of four sons born to Leone (née Feldman) and Edwin Meese, Jr. He was raised in a practicing Lutheran family, of German descent. His father was an Oakland city government official, president of the Zion Lutheran Church, and served 24 years in the non-partisan office of Treasurer of Alameda County.

At age 10, Meese published along with his brothers a mimeographed neighborhood newspaper, the Weekly Herald, and used the proceeds to buy a war bond. The young Meese also had a paper route and worked in a drugstore. At Oakland High School, Meese was involved in the Junior State of America and led his high school debate team to statewide championships. He was valedictorian of Oakland High School's class of 1949.

Two weeks prior to graduation, Meese was accepted to Yale University and granted a scholarship. At Yale, Meese served as president of the Yale Political Union, chairman of the Conservative Party, chairman of the Yale Debate Association, and a member of the secret society Spade and Grave. Meese made the dean's list, and graduated with a B.A. in political science in 1953.

Reagan Administration Attorney General

Reagan appointed Meese the successor to U.S. Attorney General William French Smith when he began his second term.[3][4] Senate confirmation of his appointment was contentious. Archibald Cox, on behalf of the lobby group Common Cause, alleged the record showed Meese had shown favoritism to financial backers, enabling them to subsequently assume positions in the first Reagan administration. The Senate confirmed his appointment by a vote of 63–31 on February 24, 1985.[5]

On May 21, 1984, Reagan had announced his intention to appoint the Attorney General to study the effect of pornography on society. The Meese Report, officially the Final Report of the Attorney General's Commission on Pornography, convened in the spring of 1985 and published its findings in July 1986. The Meese Report advised that pornography was in varying degrees harmful. Following its release, guidelines of the Department of Justice were modified to enable the government to file multiple cases in various jurisdictions at the same time, which eroded some of the markets for pornography.

In 1989 testified before Congress that he had been concerned that Reagan might face impeachment over the Iran-Contra affair.[6]

In March of 1989, Meese was called as a witness, by the prosecution, in the trial of former Reagan aide Oliver North.[7] North was on trial for the illegal shredding of documents, and Meese confirmed the fears within the senior elements of the Reagan administration that Reagan was at risk of being impeached.[8]

Attribution

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

References

- ↑ Lou Cannon (2005). Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power. PublicAffairs, 592. ISBN 9781586482848. Retrieved on 2022-12-17.

- ↑ Richard Wirthlin, Wynton C. Hall (2004). The Greatest Communicator: What Ronald Reagan Taught Me About Politics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471736486. Retrieved on 2022-12-17.

- ↑ CQ Almanac Online Edition. Retrieved on 2021-01-23. -->

- ↑ Leslie Maitland Warner. Common Cause Bids Senate Vote against Meese, The New York Times, 1984-12-19, p. A19. Retrieved on 2021-01-23. “The independent counsel's investigation focused on allegations that Mr. Meese had helped arrange positions in the Reagan Administration for individuals who had assisted him financially and that he had failed to disclose, as required by law, a $15,000 interest-free loan to his wife.” -->

- ↑ Leslie Maitland Warner. Senate Approves Meese to Become Attorney General, The New York Times, 1985-02-24.

- ↑ Texan Acts for Impeachment, The New York Times, 1987-03-06, p. 18.

- ↑ David Johnston. Meese Testifies That Impeachment Was a Worry, The New York Times, 1989-03-29, p. 17. “Mr. Meese was not asked today to explain precisely what actions he feared might constitute an impeachable offense. Mr. Meese said Mr. Reagan did not know of the diversion before his brief inquiry. But the documentary record that might confirm that account is incomplete because of the shredding of documents by Mr. North and others. 'That Spelled Touble'.” mirror

- ↑ The True Oliver North Outrage, The New York Times, 1991-05-30, p. A24. Retrieved on 2022-12-17. “Mr. North's silence posed a dilemma. Congress and the public demanded rapid exposure of what might turn out to be impeachable conduct. But forcing Mr. North and others to testify, even under court-ordered immunity, might complicate any attempt to prosecute him.”