Dokdo (Takeshima)/Debate Guide: Difference between revisions

imported>Chunbum Park mNo edit summary |

imported>Chunbum Park mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

The debate guide will examine most of the arguments that have been put forth by the academics, and it will echo the academic consensus that favors the Korean position in the dispute. | The debate guide will examine most of the arguments that have been put forth by the academics, and it will echo the academic consensus that favors the Korean position in the dispute. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

The Dokdo-Takeshima dispute can be divided into two main sets of arguments, which | The Dokdo-Takeshima dispute can be divided into two main sets of arguments, which concern the issue of historical ownership and the [[international law]]. Historical evidence dating back hundreds of years may provide moral weight to the case and is also the basis for some of the legal aspects of the dispute, but the more important is the international law with regard to what happened since 1905, when Japan issued ''Shimane Prefecture Notice No. 40'' that incorporated Dokdo as a Japanese territory under the claim of ''terra nullius''. Even if the islets were to have been native to Korea, the failure to respond to claims of ownership would equate | ||

Revision as of 22:45, 12 September 2010

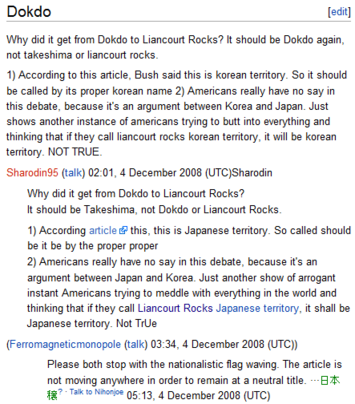

A pro-Japanese sockpuppet (Sharodin95) in Wikipedia plays the ignorant and overly nationalistic Korean "POV." The admin refuses to recognize Sharodin95 as a foiled attempt at mimicry of KPOV.

The territorial dispute between South Korea and Japan over Dokdo is an issue that can be easily misunderstood without an extensive survey of the arguments presented in academic setting. For the layman who is new to the dispute, understanding the Dokdo-Takeshima dispute is made trickier by the fact that his or her primary source of information and dialogue on the dispute would be the internet. Because the news outlets outside Korea and Japan are primarily interested in the new developments in the dispute, they avoid addressing the issue of historical correctness while providing only the general facts. Without more being provided by the official sources, the layman can only speculate that both parties involved have equal footing, or, even worse, that the side with weaker claims has aggressively escalated and prolonged the dispute (i.e. by taking control of the disputed territory).

With limited knowledge, evaluating the dispute then largely rests on the imagery of the two countries and the opinions of other netizens, who are usually biased towards Japan and may have corresponding anti-Korean sentiments. This is mainly due to the fact that Japan is a technological and cultural powerhouse, with a large fan base around the world that is very active in online communities. These pro-Japanese netizens tend to engage in what is loosely termed as "Korea-bashing," while defending Japan from antagonistic relations with Korea that is well rooted in Japan's militaristic past. In the discourse of -bashing, the images of North Korea are conjured up to depict (South) Koreans as unreasonable, aggressive, and yet immature and weak, and the Japanese, as reasonable, passive, mature, and technologically and culturally superior, which is reminiscent of the western construct of the totalitarian portrait of the Orient during the colonial era. The territorial dispute becomes another instance in which the pro-Japanese must defend Japan's claims while assuming the identity of the Japanese nation in person. The smaller opposing camp that claims the side of historical justice plays well into the role of the irrational, isolated, and overly emotional Koreans, while enabling the pro-Japanese trolls to attack in a legalistic and cool-headed manner.

A very relevant example of such clash involving the Dokdo-Takeshima controversy would be the naming disputes at Wikipedia from 2004 to 2008. A combination of favoritism by admins and well-played out sock-puppetry (or the attempt to manipulate discussions by assuming multiple personalities) have led to a situation in which the article on "Liancourt Rocks" is permanently locked from editing, and its contents as well as the title have been declared as the "consensus." But the "consensus" was arbitrarily defined based on the results of a poll that was only cleared of pro-Korean sockpuppets in a last-minute search. And, more importantly, the consensus cannot be tested nor a shift in consensus be observed if "naming lameness" and "blatant POV" are "strictly forbidden."

Even if Wikipedia's policy of Neutral Point of View must be observed, "Liancourt Rocks" as a title is unacceptable because it deliberately denies the de facto sovereignty of a country over the territory by its neutral naming. The article instead imposes a description of its own choice (neither South Koreans nor Japanese call the islets "Liancourt Rocks"), thereby prescribing a position that the status quo is genuinely disputable. This is problematic because not all issues are disputable, and the very act of disputing does not somehow make equal all sides of a dispute. The neutral naming perpetuates passive aggression on part of the Japanese side by suggesting that South Korea would be "illegally" occupying the islets, since its territorial rights are under question, but not Japan's act of disputing. It should be noted that Wikipedia's NPOV and the media's neutrality are distinctly different, since the latter usually does not designate a neutral third alternative to the "Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese." In that sense, Wikipedia's Neutral Point of View is ironically a point of view, unlike neutrality of the media, but the layman is unable to distinguish between them. Once the layman is exposed to Wikipedia's neutral designation he or she believes the Neutral Point of View and its underlying implications to be the conventional understanding of the dispute.

Unlike the layman, the academic involved in the dispute is able to determine which side has a stronger case by rigorously examining the intricacies of the arguments and their supporting evidence. Thus, there is a huge perception gap regarding the dispute between the concerned academic experts and the journalists as well as their laymen readership. Within the academic realm, the Dokdo-Takeshima dispute is mostly considered a concluded matter that will have absolutely zero impact on the Korean sovereignty over Dokdo for an indefinite period of time. The academic consensus is that South Korea has much stronger claims both historically and under the international law, and Japan will not risk war to challenge the occupation in the status quo. In fact the real priorities of South Korea and Japan currently lie in forging a new military and economic alliance to counterbalance the rise of China, and the various movements seen on the both sides of the aisle marking the 100th anniversary of the Japanese annexation of Korea were indicative of such intentions. Despite these circumstances, Japan will most likely continue to protest South Korea's control of Dokdo because disowning the islets carry a serious risk of political backlash from the Japanese Hard Right.

The debate guide will examine most of the arguments that have been put forth by the academics, and it will echo the academic consensus that favors the Korean position in the dispute.

The Dokdo-Takeshima dispute can be divided into two main sets of arguments, which concern the issue of historical ownership and the international law. Historical evidence dating back hundreds of years may provide moral weight to the case and is also the basis for some of the legal aspects of the dispute, but the more important is the international law with regard to what happened since 1905, when Japan issued Shimane Prefecture Notice No. 40 that incorporated Dokdo as a Japanese territory under the claim of terra nullius. Even if the islets were to have been native to Korea, the failure to respond to claims of ownership would equate

Historical ownership

International law

notes

Korea claims territorial sovereignty over Dokdo based on historical control of Dokdo beginning with the conquest of Ulleungdo by Shilla in 512 A.D. and subsequent de facto control based on visibility from Ulleungdo, which is the nearest historically inhabited Korean island from Dokdo. Japan claims territorial sovereignty based on activities including fishing and felling of bamboo groves at Dokdo from mid-17th century on. Korea claims that prohibition of seafaring to this area since 1696 by the Japanese government applied only to Ulleungdo, while Korea maintains that the ban applied Ulleungdo and appurtenant islands including Dokdo. Many maps, both Korean and Japanese, before 1905 show Dokdo as a Korea territory. On January 28, 1905 during the Russo-Japanese war, . The Korean government was not notified until March 29, 1906, well after Japan defeated Russia and concluded, on November 17, 1905, the Eulsa treaty that made Korea a protectorate of Japan amd prevented Korea from lodging any protest against the Japanese action over Dokdo.