Streptococcus pneumoniae: Difference between revisions

imported>Robert Badgett (More organizing) |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

''S. pneumoniae'' is commonly found in the [[upper respiratory tract]] of humans, specifically the [[nasopharynx]] region. It is found in 5-10% of healthy adults, and 20-40% of healthy children. ''S. pneumoniae'' is non-pathogenic unless it travels outside the normal inhabited region, where it will then become [[pathogenic]] and cause different infections depending on the area in which it makes its way into.< | ''S. pneumoniae'' is commonly found in the [[upper respiratory tract]] of humans, specifically the [[nasopharynx]] region. It is found in 5-10% of healthy adults, and 20-40% of healthy children. ''S. pneumoniae'' is non-pathogenic unless it travels outside the normal inhabited region, where it will then become [[pathogenic]] and cause different infections depending on the area in which it makes its way into.<ref> | ||

''S. pneumoniae'' sometimes shares its normal habitat with the pathogen [[Haemophilus influenzae]]. Individually each pathogen thrives on its own. However, when both pathogens inhabit the region at the same time, after 2 weeks only ''H. influenzae'' survives. Immune response caused by ''H. influenzae'' leads to the death of S. pneumoniae. | ''S. pneumoniae'' sometimes shares its normal habitat with the pathogen [[Haemophilus influenzae]]. Individually each pathogen thrives on its own. However, when both pathogens inhabit the region at the same time, after 2 weeks only ''H. influenzae'' survives. Immune response caused by ''H. influenzae'' leads to the death of S. pneumoniae. | ||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

Revision as of 14:07, 12 July 2010

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae |

[[Image:.]]

Description and significance

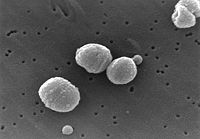

Streptococcus pneumoniae, also called pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, pathogenic bacterium capable of causing numerous infections. It the most common cause of pneumonia and bacterial meningitis, and is commonly found in the upper respiratory tract of humans. S. pneumoniae is shaped like a lancet, a type of knife with a short wide two-edged blade. It is alpha hemolytic (a classification method using the breakdown of red blood cells) and is usually between 0.5 and 1.25 micrometers in size.[1][2]

S. pneumoniae was first isolated in 1881 simultaneously by U.S. Army physician George Sternberg and French chemist Louis Pasteur. S. pneumoniae has been used to prove that genetic material consists of DNA. In 1928 Frederick Griffith co-inoculated live pneumococci into a mouse along with heat-killed, virulent pneumococci. The live, harmless pneumococci were transformed into the lethal form. In 1944 Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty found that the transforming factor in Griffith's experiment was DNA. [3]

Genome structure

S. pneumoniae has a 2,160,837 base pair genome sequence. Its chromosome is circular and has 2236 coding regions. Approximately 5% of the genome is composed of insertion sequences that may contribute to genome rearrangements through uptake of foreign DNA. S. pneumoniae has shown a significant increase in antibiotic resistance over the past few decades, due to its rapid growth rate and genetic rearrangements.[4][5]

Cell structure and metabolism

S. pneumoniae is completely surrounded by a capsule made up of polysaccharides. The capsule interferes with phagocytosis by preventing opsonization of its cells. The cell wall of S. pneumoniae is six layers thick and made up of peptidoglycan with teichoic and lipoteichoic acids. Within these acids are choline-binding proteins (CBPs), which adhere to choline receptors on human cells. S. pneumoniae has pili, which are hair-like structures extending from its surface. It also has more than 500 surface proteins, including five penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), two neuraminidases, an IgA protease, as well as choline-binding proteins as stated previously.[6]

S. pneumoniae gains a substantial amount of carbon and nitrogen using extracellular enzyme systems which allow for the metabolism of polysaccharides and hexosamines. These systems also damage host tissues and facilitate colonization.[7]

Ecology

S. pneumoniae is commonly found in the upper respiratory tract of humans, specifically the nasopharynx region. It is found in 5-10% of healthy adults, and 20-40% of healthy children. S. pneumoniae is non-pathogenic unless it travels outside the normal inhabited region, where it will then become pathogenic and cause different infections depending on the area in which it makes its way into.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

S. pneumoniae has several virulence factors which enable it to evade the human immune system. It has a polysaccharide capsule, which interferes with phagocytosis by preventing opsonization of its cells. It has pneumolysin, a protein that causes lysis of host cells and prevents activation of the complement pathway. It also has autolysin, which lyses its own cells to release its contents. Other virulence factors include hydrogen peroxide, pili, and choline binding protein.[8]

Vaccination

The reason it is difficult to pinpoint a vaccination is due to the fact that over 90 serotypes of S. pneumoniae exist, and that immunization with a one serotype does not protect against infection with other serotypes. Vaccinations currently in use target multiple serotypes. Young children (under 60 months) are given a heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV 7) such as Prevnar.

A recent study showed that a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduced in children in the year 2000 showed a significant decrease in effect after 4 years. The 7-Valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was introduced in children in 2000, and the proportion of S. pneumoniae isolates susceptible to the antibiotic was tested yearly. After 4 years, the proportion of susceptible isolates decreased significantly, showing that S. pneumoniae builds resistance to antibiotics fairly rapidly.[9]

S. pneumoniae vaccines are typically injected into the body, however a study conducted research using vaccines administered using the intranasal route had successful results in animals. Using unencapsulated killed whole-cell pneumococci of the type 6B strain, researchers administered the vaccine intranasally into rats. The vaccine proved protect the animal from infection.[10]

Current research

New serotypes are still being discovered. A recent study found a new capsular serotype of S. pneumoniae. Researchers found a new subtype within serotype 6. Two subtypes (A & B) were already known, however a subtype C has now been discovered. This study showed that serotypes can be found within already established serotypes.[11]

References

- ↑ Medicinenet: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Textbook of Bacteriology: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Wikipedia: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 Genome Page

- ↑ Textbook of Bacteriology: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Textbook of Bacteriology: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Textbook of Bacteriology: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Textbook of Bacteriology: Streptococcus pneumoniae

- ↑ Farrell, D., Klugman, K., Pichichero, M. "Increased Antimicrobial Resistance Among Nonvaccine Serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the Pediatric Population After the Introduction of 7-Valent Pneumococcal Vaccine in the United States". Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. February 2007. Vol. 26. p. 123-128.

- ↑ Malley, R., Lipsitch, M., Stack, A., Saladino, R., Fleisher, G., Pelton, S., Thompson, C., Briles, D., and Anderson, P. "Intranasal Immunization with Killed Unencapsulated Whole Cells Prevents Colonization and Invasive Disease by Capsulated Pneumococci". Infection and Immunity. August 2001. Vol. 69. p. 4870-4873.

- ↑ Park, I., Pritchard, D., Cartee, R., Brandao, A., Brandileone, M., and Nahm, M. "Discovery of a New Capsular Serotype (6C) within Serogroup 6 of Streptococcus pneumoniae". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. April 2007. Vol. 45. p. 1225-1233.