DNA/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>Gareth Leng (→Supercoiling: rmv ?redundant ref?) |

imported>Gareth Leng |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

===Base modifications=== | ===Base modifications=== | ||

{{further|[[DNA methylation]]}} | {{further|[[DNA methylation]]}} | ||

The expression of genes is influenced by the [[chromatin]] structure of a chromosome and regions of [[heterochromatin]] (low or no gene expression) correlate with the [[methylation]] of [[cytosine]]. For example, cytosine methylation, to produce [[5-Methylcytosine|5-methylcytosine]], is important for [[X-inactivation|X-chromosome inactivation]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Klose R, Bird A | title = Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators | journal = Trends Biochem Sci | volume = 31 | issue = 2 | pages = 89 – 97 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16403636}}</ref> The average level of methylation varies between organisms, with ''[[Caenorhabditis elegans]]'' lacking cytosine methylation, while [[vertebrate]]s show higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Bird A | title = DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory | journal = Genes Dev | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = 6 – 21 | year = 2002 | id = PMID 11782440}}</ref> Despite the biological role of 5-methylcytosine it is susceptible to spontaneous [[deamination]] to leave the thymine base, and methylated cytosines are therefore [[mutation]] hotspots.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Walsh C, Xu G | title = Cytosine methylation and DNA repair | journal = Curr Top Microbiol Immunol | volume = 301 | issue = | pages = 283 – 315 | year = | id = PMID 16570853}}</ref> Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria and the [[glycosylation]] of uracil to produce the "J-base" in [[kinetoplastid]]s.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ratel D | The expression of genes is influenced by the [[chromatin]] structure of a chromosome and regions of [[heterochromatin]] (low or no gene expression) correlate with the [[methylation]] of [[cytosine]]. For example, cytosine methylation, to produce [[5-Methylcytosine|5-methylcytosine]], is important for [[X-inactivation|X-chromosome inactivation]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Klose R, Bird A | title = Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators | journal = Trends Biochem Sci | volume = 31 | issue = 2 | pages = 89 – 97 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16403636}}</ref> The average level of methylation varies between organisms, with ''[[Caenorhabditis elegans]]'' lacking cytosine methylation, while [[vertebrate]]s show higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Bird A | title = DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory | journal = Genes Dev | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = 6 – 21 | year = 2002 | id = PMID 11782440}}</ref> Despite the biological role of 5-methylcytosine it is susceptible to spontaneous [[deamination]] to leave the thymine base, and methylated cytosines are therefore [[mutation]] hotspots.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Walsh C, Xu G | title = Cytosine methylation and DNA repair | journal = Curr Top Microbiol Immunol | volume = 301 | issue = | pages = 283 – 315 | year = | id = PMID 16570853}}</ref> Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria and the [[glycosylation]] of uracil to produce the "J-base" in [[kinetoplastid]]s.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ratel D ''et al.''| title = N6-methyladenine: the other methylated base of DNA | journal = Bioessays | volume = 28 | pages = 309 – 15 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16479578}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Gommers-Ampt J ''et al.''| title = beta-D-glucosyl-hydroxymethyluracil: a novel modified base present in the DNA of the parasitic protozoan T. brucei | journal = Cell | volume = 75 | pages = 1129 – 36 | year = 1993 | id = PMID 8261512}}</ref> | ||

===DNA damage and mutations=== | ===DNA damage and mutations=== | ||

Revision as of 10:12, 11 June 2007

Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a very large biological molecule that is vital in providing information for the development and reproduction of living things. Inheritable variation in DNA is the single most important factor forcing evolutionary change to occur in multiply successive generations of organisms. Yet, there are many types of macromolecules in living things, and there exists all sorts of chemical variability between them at any one time. We know, as experimentally proven fact, that nearly all classes of macromolecules show variations between the generations in the most rapidly reproducing organisms, bacteria, and we must asume that there are similar changes in the biochemistry of each kind of living thing, including those with long generation spans, over all the ages of life on earth. Beyond these general descriptive characteristics, then, what "exactly" is DNA? What are the precise physical attributes of this molecule that make its role so centrally imposing in understanding organic life?

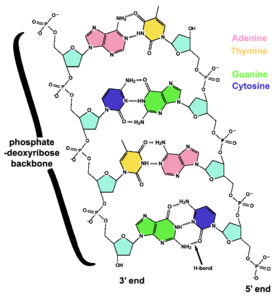

DNA is a long polymer of simple units called nucleotides, held together by a sugar phosphate backbone. Attached to each sugar molecule is a molecule of one of four bases; adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G) or cytosine (C), and the order of these bases on the DNA strand encodes information. In most organisms, DNA is a double-helixconsisting of two complementary DNA strands coiled around each other, and held together by hydrogen bonds between bases. Because of the chemical nature of these bases, adenine always pairs with thymine and guanine always pairs with cytosine. This complementarity forms the basis of semi-conservative DNA replication - it makes it possible for the large DNA molecule to be copied relatively simply.

The entire DNA sequence of an organism is called its genome, and it consists of coding regions called genes and non-coding regions. The coding regions are transcribed into ribonucleic acid (RNA), and many of the transcribed RNA sequences are then translated into the amino acid sequences of single polypeptide chains. Polypeptide chains form proteins, the molecules that perform important regulatory, catalytic and structural roles in cells. Other RNA molecules (e.g. rRNA,tRNA,mRNA, RNAi) perform other important catalytic and regulatory tasks.

In animals and plants, most DNA is stored inside the cell nucleus. In bacteria, the DNA is found in the cell's cytoplasm. Viruses have a single type of nucleic acid, either DNA (or RNA) directly encased in a protein coat (although some viruses have, additionally an outer lipid envelope).

Overview of biological functions

DNA contains the genetic information that allows living things to function, grow, reproduce and evolve. This information is held in the sequence of pieces of DNA called genes. When a cell uses the information in a gene, the DNA sequence is copied into a complementary RNA sequence in a process called transcription. Usually, this RNA copy is then used to make a matching protein sequence in a process called translation. Alternatively, a cell may simply copy its genetic information in a process called DNA replication. The details of these functions are covered in other articles, here we focus on the interactions that happen in these processes between DNA and other molecules.

Genes

Transcription and translation

- Further information: Genetic code, Transcription (genetics), Protein biosynthesis

Within a gene, the sequence of bases defines a messenger RNA (mRNA) sequence which then defines a protein sequence. The relationship between the nucleotide sequences of genes and the amino-acid sequences of proteins is determined by the rules of translation, known as the genetic code. The genetic code consists of three-letter 'words' called codons formed from a sequence of three nucleotides (e.g. ACT, CAG, TTT). In transcription, the codons of a gene are copied into mRNA by RNA polymerase. This RNA copy is then decoded by a ribosome that reads the RNA sequence by base-pairing the mRNA to transfer RNA (tRNA), which carries amino acids. As there are four bases in three-letter combinations, there are 64 possible codons, and these encode the twenty standard amino acids. Most amino acids, therefore, have more than one possible codon. There are also three 'stop' or 'nonsense' codons (TAA, TGA and TAG) that signify the end of the coding region.

Regulation of gene expression

Physical and chemical properties

DNA is a long polymer made from repeating units called nucleotides (a nucleotide is a base linked to a sugar and one or more phosphate groups)[1][2] The DNA chain is 22 to 26 angstroms wide (2.2 to 2.6 nanometers) [3] The nucleotides are very small (just 3.3 angstroms long), but DNA polymers can contain millions of them: the DNA strand in the largest human chromosome (Chromosome 1) has 220 million base pairs.[4]

In living organisms, DNA does not usually exist as a single molecule, but as a tightly-associated pair of molecules.[5][6] These two long strands are entwined in the shape of a double helix. DNA can thus be thought of as an anti-parallel double helix. The nucleotide repeats contain both the backbone of the molecule, which holds the chain together, and a base, which interacts with the other DNA strand in the helix. If many nucleotides are linked together, as in DNA, the polymer is referred to as a polynucleotide.[7]

The backbone of the DNA strand has alternating phosphate and sugar residues.[8] The sugar in DNA is the pentose (five carbon) sugar 2-deoxyribose. The sugars are joined together by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms in the sugar rings. These asymmetric bonds mean that a strand of DNA has a direction. In a double helix, the direction of the nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other strand. This arrangement of DNA strands is called antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of a strand of DNA bases are referred to as the 5' (five prime) and 3' (three prime) ends. One of the major differences between DNA and RNA is the sugar, with 2-deoxyribose being replaced by the alternative pentose sugar ribose in RNA.[6]

The DNA double helix is held together by hydrogen bonds between the bases attached to the two strands. The four bases in DNA are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T), and these bases are attached to the sugar/phosphate to form the complete nucleotide. Adenine and guanine are fused five- and six-membered heterocyclic compounds called purines, while cytosine and thymine are six-membered rings called pyrimidines.[7] A fifth pyrimidine base, uracil (U), replaces thymine in RNA and differs from thymine in lacking a methyl group on its ring. Uracil is normally only found in DNA as a breakdown product of cytosine, but bacterial viruses such as phage PBS1 contain uracil in its DNA.[9] In contrast, following synthesis of certain RNA molecules, a significant number of uracils are converted to thymines by the enzymatic addition of the missing methyl group. This occurs mostly on structural and enzymatic RNAs like tRNAs and ribosomal RNA.[10]

The double helix is a right-handed spiral. As the DNA strands wind around each other, gaps between each set of phosphate backbones reveal the sides of the bases inside (see animation). There are two of these grooves twisting around the surface of the double helix: the major groove is 22 Å wide and the minor groove is 12 Å wide.[11] The edges of the bases are more accessible in the major groove, so proteins like transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contacts to the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.[12]

Base pairing

- Further information: Base pair

Each type of base on one strand forms a bond with just one type of base on the other strand. This is called complementary base pairing. Here, purines form hydrogen bonds to pyrimidines, with A bonding only to T, and C bonding only to G. This arrangement of two nucleotides joined together across the double helix is called a base pair. In a double helix, the two strands are also held together by forces generated by the hydrophobic effect and by a nucleic-acid-specific variation of pi stacking, which are not influenced by the sequence of the DNA.[13] As hydrogen bonds are not covalent, they can be broken and rejoined relatively easily. The two strands of DNA in a double helix can therefore be pulled apart like a zipper, either by a mechanical force or high temperature.[14] As a result of this complementarity, all the information in the double-stranded sequence of a DNA helix is duplicated on each strand, which is vital in DNA replication. Indeed, this reversible and specific interaction between complementary base pairs is critical for all the functions of DNA in living organisms.[1] Kornberg considers the introduction of the concept of complementarity as the most important feature of the duplex model for DNA structure.

The two types of base pairs form different numbers of hydrogen bonds; AT forms two hydrogen bonds, and GC forms three, so the GC base-pair is stronger than the AT base pair. Thus, long DNA helices with a high GC content have strongly interacting strands, while short helices with high AT content have weakly interacting strands.[15] Parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the TATAAT Pribnow box in bacterial promoters, tend to have sequences with a high AT content, making the strands easier to pull apart.[16] In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be measured by finding the temperature required to break the hydrogen bonds, their melting temperature (also called Tm value). When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules. These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single shape, but some conformations are more stable than others. [17] The base pairing, or lack of it, can create various topologies at the DNA end. These can be exploited in biotechnology.

Sense and antisense

- Further information: Sense (molecular biology)

DNA is copied into RNA by RNA polymerase enzymes that only work in the 5' to 3' direction. [18] A DNA sequence is called "sense" if its sequence is copied by these enzymes and then translated into protein. The sequence on the opposite strand is complementary to the sense sequence and is called the "antisense" sequence. Both sense and antisense sequences can exist on different parts of the same strand of DNA. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, antisense sequences are transcribed [19], and one proposal is that antisense RNAs are involved in regulating gene expression through RNA-RNA base pairing.[20]. (See Micro RNA, RNA interference, sRNA.)

Many DNA sequences in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and more in plasmids and viruses, have overlapping genes which may both occur in the same direction, on the same strand (parallel) or in opposite directions, on opposite strands (antiparallel), thus bluring the distinction made above between sense and antisense strands.[21][22] In these cases, some DNA sequences do double duty, encoding one protein when read 5′ to 3′ along one strand, and a second protein when read in the opposite direction (still 5′ to 3′) along the other strand. In bacteria, this overlap may be involved in the regulation of gene transcription,[22] while in viruses, overlapping genes increase the amount of information that can be encoded within the small viral genome.[23] Another way of reducing genome size is seen in some viruses that contain linear or circular single-stranded DNA as their genetic material.[24][25]

Supercoiling

- Further information: DNA supercoil

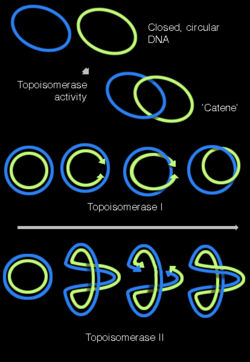

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called DNA supercoiling. In its "relaxed" state, a DNA strand usually circles the axis of the double helix once every 10.4 base pairs, but if the DNA is twisted the strands become more tightly or more loosely wound.[26] If the DNA is twisted in the direction of the helix, this is positive supercoiling, and the bases are held more tightly together. If they are twisted in the opposite direction, this is negative supercoiling, and the bases come apart more easily. In nature, most DNA has slight negative supercoiling that is introduced by enzymes called topoisomerases. These enzymes are also needed to relieve the twisting stresses introduced into DNA strands during processes such as transcription and DNA replication.[27]

Alternative double-helical structures

- Further information: Mechanical properties of DNA

DNA exists in several possible conformations. The conformations so far identified are: A-DNA, B-DNA, C-DNA, D-DNA,[28] E-DNA,[29] H-DNA,[30] L-DNA,[28] and Z-DNA.[8][31] However, only A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA are believed to be found in naturally occurring biological systems. Which conformation DNA adopts depends on the sequence of the DNA, the amount and direction of supercoiling, chemical modifications of the bases and also solution conditions, such as the concentration of metal ions and polyamines.[32] Of these three conformations, the "B" form described above is most common under the conditions found in cells. The two alternative double-helical forms of DNA differ in their geometry and dimensions.

The A form is a wider right-handed spiral, with a shallow and wide minor groove and a narrower and deeper major groove. The A form occurs under non-physiological conditions in dehydrated samples of DNA, while in the cell it may be produced in hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, as well as in enzyme-DNA complexes.[33][34] Segments of DNA where the bases have been chemically-modified by methylation may undergo a larger change in conformation and adopt the Z form. Here, the strands turn about the helical axis in a left-handed spiral, the opposite of the more common B form.[35] These unusual structures can be recognised by specific Z-DNA binding proteins and may be involved in the regulation of transcription.[36]

Quadruplex structures

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called telomeres. Their main function is to allow the cell to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase, as normal DNA polymerases working on the lagging strand cannot copy the extreme 3' ends of their DNA templates.[37] If a chromosome lacked telomeres it would become shorter each time it was replicated. These specialized chromosome caps also help protect the DNA ends from exonucleases and stop the DNA repair systems in the cell from treating them as damage to be corrected.[38] In human cells, telomeres are usually lengths of single-stranded DNA containing several thousand repeats of a simple TTAGGG sequence.[39]

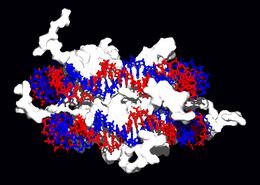

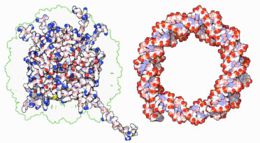

These guanine-rich sequences may stabilise chromosome ends by forming very unusual quadruplex structures. Here, four guanine bases form a flat plate, through hydrogen bonding, and these flat four-base units then stack on top of each other, to form a stable quadruplex.[40] These structures are often stabilized by chelation of a metal ion in the centre of each four-base unit. The structure shown to the left is of a quadruplex formed by a DNA sequence containing four consecutive human telomere repeats. The single DNA strand forms a loop, with the sets of four bases stacking in a central quadruplex three plates deep. In the space at the centre of the stacked bases are three chelated potassium ions.[41] Other structures can also be formed and the central set of four bases can come from either one folded strand, or several different parallel strands, each contributing one base to the central structure.

Telomeres also form large loop structures called 'telomere loops', or 'T-loops'. Here, the single-stranded DNA curls around in a circle stabilized by telomere-binding proteins.[42] The very end of the T-loop, the single-stranded telomere DNA is held onto a region of double-stranded DNA by the telomere strand disrupting the double-helical DNA and base pairing to one of the two strands. This triple-stranded structure is called a 'displacement loop', or 'D-loop'.[40]

Chemical modifications

Base modifications

- Further information: DNA methylation

The expression of genes is influenced by the chromatin structure of a chromosome and regions of heterochromatin (low or no gene expression) correlate with the methylation of cytosine. For example, cytosine methylation, to produce 5-methylcytosine, is important for X-chromosome inactivation.[43] The average level of methylation varies between organisms, with Caenorhabditis elegans lacking cytosine methylation, while vertebrates show higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine.[44] Despite the biological role of 5-methylcytosine it is susceptible to spontaneous deamination to leave the thymine base, and methylated cytosines are therefore mutation hotspots.[45] Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria and the glycosylation of uracil to produce the "J-base" in kinetoplastids.[46][47]

DNA damage and mutations

- Further information: Mutation

DNA can be damaged by many different agents, most of which induce mutations (i.e. are mutagens). These agents include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light and x-rays. Lesions of DNA, in which residues are changed to a structure that is not a normal feature of DNA, are distinct from mutations, which are alterations of a DNA base to another base normally present in DNA. Damaged DNA can give rise to mutations, and indeed, some DNA repair processes are error prone and thus themselves generate mutations.

The type of DNA damage depends on the type of agent that causes it. UV light damages DNA mostly by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between adjacent pyrimidine bases in a DNA strand.[48] On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide produce several forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, as well as double-strand breaks.[49] It has been estimated that in each human cell, about 500 bases suffer oxidative damage per day.[50][51] Of these oxidative lesions, the most damaging are double-strand breaks, as they can produce point mutations, insertions and deletions from the DNA sequence, as well as chromosomal translocations.[52]

Many mutagens intercalate into the space between two adjacent base pairs. These molecules are mostly polycyclic, aromatic, and planar molecules and include ethidium, proflavin, daunomycin, doxorubicin and thalidomide. DNA intercalators are used in chemotherapy to inhibit DNA replication in rapidly-growing cancer cells.[53] For an intercalator to fit between base pairs, the bases must separate, distorting the DNA strand by unwinding of the double helix. These structural modifications inhibit transcription and replication processes, causing both toxicity and mutations. As a result, DNA intercalators are often carcinogens, with benzopyrene diol epoxide, acridines, aflatoxin and ethidium bromide being well-known examples.[54][55] Nevertheless, due to their properties of inhibiting DNA transcription and replication, they are also used in chemotherapy to inhibit rapidly-growing cancer cells.[56]

Replication

- Further information: DNA replication, Replication of a circular bacterial chromosome

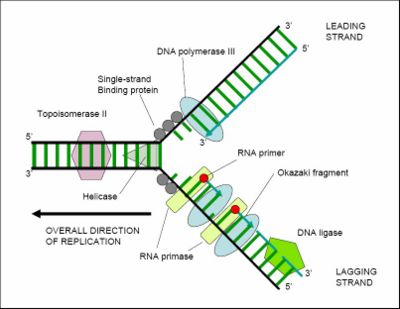

Cell division is essential for an organism to grow, but when a cell divides it must replicate the DNA in its genome so that the two daughter cells have the same genetic information as their parent. The double-stranded structure of DNA provides a simple mechanism for DNA replication. Here, the two strands are separated and then each strand's complementary DNA sequence is recreated by an enzyme called DNA polymerase. This enzyme makes the complementary strand by finding the correct base through complementary base pairing, and bonding it onto the original strand. As DNA polymerases can only extend a DNA strand in a 5' to 3' direction, different mechanisms are used to copy the antiparallel strands of the double helix.[57] In this way, the base on the old strand dictates which base appears on the new strand, and the cell ends up with a perfect copy of its DNA.

Despite the apparent simplicity of DNA replication, the duplication of DNA prior to cell division is carried out by a complex and efficient set of catalytically active proteins, each dedicated to the different tasks needed to replicate this large molecule in an orderly and extremely precise fashion. Further capacity for DNA replication with substantial rearrangement (which has major implications for understanding mechanisms of molecular evolution, is provided by mechanisms for DNA movement, inversion, and duplication, illustrated by various mobile DNAs such as transposons and proviruses.

Genes and genomes

- Further information: Cell nucleus, Gene, Non-coding DNA, Genomics

DNA is located in the cell nucleus of eukaryotes, as well as small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.[58] The DNA is usually in linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. In the human genome, there are about three billion base pairs of DNA arranged into 46 chromosomes.[59] The genetic information in a genome is held within genes. A gene is a unit of heredity and is a region of DNA that influences a particular characteristic in an organism. Genes contain an open reading frame that can be transcribed, as well as regulatory sequences such as promoters and enhancers, which control the expression of the open reading frame.

In many species, only a small fraction of the total sequence of the genome encodes protein. For example, only about 1.5% of the human genome consists of protein-coding exons, with over 50% of human DNA consisting of non-coding repetitive sequences.[60] The reasons for the presence of so much non-coding DNA in eukaryotic genomes and the extraordinary differences in genome size, or C-value, among species represent a long-standing puzzle known as the "C-value enigma".[61]

Some non-coding DNA sequences play structural roles in chromosomes. Telomeres and centromeres typically contain few genes, but are important for the function and stability of chromosomes.[38][62] An abundant form of non-coding DNA in humans are pseudogenes, which are copies of genes that have been disabled by mutation.[63] These sequences are usually just molecular fossils, although they can occasionally serve as raw genetic material for the creation of new genes through the process of gene duplication and divergence.[64]

Interactions with proteins

All the functions of DNA depend on interactions with proteins. These protein interactions can either be non-specific, or the protein can only bind to a particular DNA sequence. Enzymes can also bind to DNA and of these, the polymerases that copy the DNA base sequence in transcription and DNA replication are particularly important.

DNA-binding proteins

|

|

Structural proteins that bind DNA are well-understood examples of non-specific DNA-protein interactions. Within chromosomes, DNA is held in complexes between DNA and structural proteins. These proteins organize the DNA into a compact structure called chromatin. In eukaryotes this structure involves DNA binding to a complex of small basic proteins called histones, while in prokaryotes multiple types of proteins are involved.[65] The histones form a disk-shaped complex called a nucleosome, which contains two complete turns of double-stranded DNA wrapped around its surface. These non-specific interactions are formed through basic residues in the histones making ionic bonds to the acidic sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA, and are therefore largely independent of the base sequence.[66] Chemical modifications of these basic amino acid residues include methylation, phosphorylation and acetylation.[67] These chemical changes alter the strength of the interaction between the DNA and the histones, making the DNA more or less accessible to transcription factors and changing the rate of transcription.[68] Other non-specific DNA-binding proteins found in chromatin include the high-mobility group proteins, which bind preferentially to bent or distorted DNA.[69] These proteins are important in bending arrays of nucleosomes and arranging them into more complex chromatin structures.[70]

A distinct group of DNA-binding proteins are the single-stranded DNA-binding proteins. that specifically bind single-stranded DNA. In humans, replication protein A is the best-characterised member of this family and is essential for most processes where the double helix is separated, including DNA replication, recombination and DNA repair.[71] These binding proteins seem to stabilize single-stranded DNA and protect it from forming stem loops or being degraded by nucleases.

In contrast, other proteins have evolved to specifically bind particular DNA sequences. The most intensively studied of these are the various classes of transcription factors. These proteins control gene transcription. Each one of these proteins bind to one particular set of DNA sequences and thereby activates or inhibits the transcription of genes with these sequences close to their promoters. The transcription factors do this in two ways. Firstly, they can bind the RNA polymerase responsible for transcription, either directly or through other mediator proteins, this locates the polymerase at the promoter and allows it to begin transcription.[72] Alternatively, transcription factors can bind enzymes that modify the histones at the promoter, this will change the accessibility of the DNA template to the polymerase.[73]

As these DNA targets can occur throughout an organism's genome, changes in the activity of one type of transcription factor can affect thousands of genes.[74] Consequently, these proteins are often the targets of the signal transduction processes that mediate responses to environmental changes or cellular differentiation and development. The specificity of these transcription factors' interactions with DNA come from the proteins making multiple contacts to the edges of the DNA bases, allowing them to "read" the DNA sequence. Most of these base interactions are made in the major groove, where the bases are most accessible.[75]

DNA-modifying enzymes

Nucleases and ligases

Nucleases are enzymes that cut DNA strands by catalyzing the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bonds. Nucleases that hydrolyse nucleotides from the ends of DNA strands are called exonucleases, while endonucleases cut within strands. The most frequently-used nucleases in molecular biology are the restriction endonucleases, which cut DNA at specific sequences. For instance, the EcoRV enzyme recognizes the 6-base sequence 5′-GAT|ATC-3′ and makes a cut at the vertical line. In nature, these enzymes protect bacteria against phage infection by digesting the phage DNA when it enters the bacterial cell, acting as part of the restriction modification system.[76] In technology, these sequence-specific nucleases are used in molecular cloning and DNA fingerprinting.

Enzymes called DNA ligases can rejoin cut or broken DNA strands, using the energy from either adenosine triphosphate or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.[77] Ligases are particularly important in lagging strand DNA replication, as they join together the short segments of DNA produced at the replication fork into a complete copy of the DNA template. They are also used in DNA repair and genetic recombination.[77]

Topoisomerases and helicases

Topoisomerases are enzymes with both nuclease and ligase activity. These proteins change the amount of supercoiling in DNA. Some of these enzyme work by cutting the DNA helix and allowing one section to rotate, thereby reducing its level of supercoiling; the enzyme then seals the DNA break.[78] Other types of these enzymes are capable of cutting one DNA helix and then passing a second strand of DNA through this break, before rejoining the helix.[79] Topoisomerases are required for many processes involving DNA, such as DNA replication and transcription.[27]

Helicases are proteins that are a type of molecular motor. They use the chemical energy in nucleoside triphosphates, predominantly ATP, to break hydrogen bonds between bases and unwind the DNA double helix into single strands.[80] These enzymes are essential for most processes where enzymes need to access the DNA bases.

Polymerases

Polymerases are enzymes that synthesise polynucleotide chains from nucleoside triphosphates. They function by adding nucleotides onto the 3′ hydroxyl group of the previous nucleotide in the DNA strand. As a consequence, all polymerases work in a 5′ to 3′ direction.[18] In the active site of these enzymes, the nucleoside triphosphate substrate base-pairs to a single-stranded polynucleotide template: this allows polymerases to accurately synthesise the complementary strand of this template. Polymerases are classified according to the type of template that they use.

In DNA replication, a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase makes a DNA copy of a DNA sequence. Accuracy is vital in this process, so many of these polymerases have a proofreading activity. Here, the polymerase recognizes the occasional mistakes in the synthesis reaction by the lack of base pairing between the mismatched nucleotides. If a mismatch is detected, a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity is activated and the incorrect base removed.[81] In most organisms DNA polymerases function in a large complex called the replisome that contains multiple accessory subunits, such as the DNA clamp or helicases.[82]

RNA-dependent DNA polymerases are a specialised class of polymerases that copy the sequence of an RNA strand into DNA. They include reverse transcriptase, which is a viral enzyme involved in the infection of cells by retroviruses, and telomerase, which is required for the replication of telomeres.[83][37] Telomerase is an unusual polymerase because it contains its own RNA template as part of its structure.[38]

Transcription is carried out by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase that copies the sequence of a DNA strand into RNA. To begin transcribing a gene, the RNA polymerase binds to a sequence of DNA called a promoter and separates the DNA strands. It then copies the gene sequence into a messenger RNA transcript until it reaches a region of DNA called the terminator, where it halts and detaches from the DNA. As with human DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, RNA polymerase II, the enzyme that transcribes most of the genes in the human genome, operates as part of a large protein complex with multiple regulatory and accessory subunits.[84]

Genetic recombination

- Further information: Genetic recombination

A DNA helix does not usually interact with other segments of DNA, and in human cells the different chromosomes even occupy separate areas in the nucleus called "chromosome territories".[85] This physical separation of chromosomes is important for the ability of DNA to function as a stable repository for information, as one of the few times chromosomes interact is during chromosomal crossover when they recombine. Recombination is when two DNA helices break, swap a section and then rejoin. In eukaryotes, this usually occurs during meiosis, when two chromatids are paired together in the center of the cell.

Recombination allows chromosomes to exchange genetic information and produces new combinations of genes, which increases the efficiency of natural selection and can be important in the rapid evolution of new proteins.[86] Genetic recombination can also be involved in DNA repair, particularly in the cell's response to double-strand breaks.[87]

The most common form of recombination is homologous recombination, where the two chromosomes involved share very similar sequences. Non-homologous recombination can be damaging to cells, as it can produce chromosomal translocations and genetic abnormalities. The recombination reaction is catalyzed by enzymes known as recombinases, such as Cre recombinase[88] and RAD51[89], that have a DNA-dependent ATPase activity and catalyze strand exchange between homologous DNA molecules. In the first step, the recombinase creates a nick in one strand of a DNA double helix, allowing the nicked strand to pull apart from its complementary strand and anneal to one strand of the double helix on the opposite chromatid. A second nick allows the strand in the second chromatid to pull apart and anneal to the remaining strand in the first helix, forming a structure known as a cross-strand exchange or a Holliday junction. The Holliday junction is a tetrahedral junction structure which can be moved along the pair of chromosomes, swapping one strand for another. The recombination is then halted by cleavage of the junction and re-ligation of the released DNA.[90]

DNA and molecular evolution

- Further information: Molecular evolution, Phylogenetics

As well as being susceptible to largely random mutations that affect a single base, some regions of DNA are specialised to undergo dramatic, rapid, non-random, and even directed rearrangements, or to undergo more subtle changes at a high frequency so that the expression of a gene is dramatically altered. Such DNA rearrangements include various versions of site-specific recombination. This activity depends on enzymes that recognise particular sites on DNA and create novel structures such as insertions, deletions and inversions. For instance, DNA regions within the small DNA genome of the bacterial virus P1 can invert, enabling different versions of tail fibers to be expressed in different viruses. Similarly, site-specific recombinase enzymes (FLP) are responsible for mating type variation in yeast, and for flagellum type (phase) changes in the bacterium Salmonella enterica Typhimurium.

More subtle directed mutations can occur in micro-satellite repeats. An example of such a structure are short DNA intervals where the same base is tandemly repeated, as in 5'-gcAAAAAAAAAAAttg-3'.

DNA polymerase III is prone to make 'stuttering errors' at such repeats. As a consequence, change in repeat number occur relatively often during cell replication, and when they appear at a position where the spacing of nucleotide residues is critical for gene function, they can cause changes to the phenotype. In the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis (and other microbes) this enables rapid evolution and reproductive success inside the human body.

Triplet repeats behave similarly, but are particularly suited to evolution of proteins with differing characteristics. In the clock-like period gene of the fruit fly, which influences the frequency of its love-song, triplet repeats are used to fine tune an insect's clock in response different environmental temperatures. Triplet repeats are widely distributed in genomes, and their high frequency of mutation is responsible for several human genetically determined disorders.

The evolutionary significance of these concepts is charmingly discussed by Christopher Wills in The Runaway Brain: The Evolution of Human Uniqueness ISBN 0-00-654672-2 (1995).

Uses in technology

Forensics

Forensic scientists can use DNA in blood, semen, skin, saliva or hair at a crime scene to identify a perpetrator. This process is called genetic fingerprinting or more accurately, DNA profiling. In DNA profiling, the lengths of variable sections of repetitive DNA, such as short tandem repeats and minisatellites, are compared between people. This method is usually an extremely reliable technique for identifying a criminal.[91] However, identification can be complicated if the scene is contaminated with DNA from several people.[92] DNA profiling was developed in 1984 by British geneticist Sir Alec Jeffreys,[93] and first used in forensic science to convict Colin Pitchfork in the 1988 Enderby murders case.[94] People convicted of certain types of crimes may be required to provide a sample of DNA for a database. This has helped investigators solve old cases where only a DNA sample was obtained from the scene. DNA profiling can also be used to identify victims of mass casualty incidents.[95]

Bioinformatics

- Further information: Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics involves the manipulation, searching, and data mining DNA sequence data. The development of techniques to store and search DNA sequences have led to widely-applied advances in computer science, especially string searching algorithms, machine learning and database theory.[96] String searching or matching algorithms, which find an occurrence of a sequence of letters inside a larger sequence of letters, was developed to search for specific sequences of nucleotides.[97] In other applications such as text editors, even simple algorithms for this problem usually suffice, but DNA sequences cause these algorithms to exhibit near-worst-case behaviour due to their small number of distinct characters. The related problem of sequence alignment aims to identify homologous sequences and locate the specific mutations that make them distinct. These techniques, especially multiple sequence alignment, are used in studying phylogenetic relationships and protein function.[98] Data sets representing entire genomes' worth of DNA sequences, such as those produced by the Human Genome Project, are difficult to use without annotations, which label the locations of genes and regulatory elements on each chromosome. Regions of DNA sequence that have the characteristic patterns associated with protein- or RNA-coding genes can be identified by gene finding algorithms, which allow researchers to predict the presence of particular gene products in an organism even before they have been isolated experimentally.[99]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Alberts, Bruce; Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, and Peter Walters (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell; Fourth Edition. New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ↑ Butler, John M (2001) Forensic DNA Typing "Elsevier". pp. 14-15. ISBN 978-0-12-147951-0.

- ↑ Mandelkern M et al. (1981). "The dimensions of DNA in solution". J Mol Biol 152: 153-61. PMID 7338906.

- ↑ Gregory S et al. (2006). "The DNA sequence and biological annotation of human chromosome 1". Nature 441: 315-21. PMID 16710414.

- ↑ Watson J, Crick F (1953). "Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid". Nature 171: 737-8. PMID 13054692.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Berg J et al. (2002) Biochemistry. WH Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-4955-6

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Abbreviations and Symbols for Nucleic Acids, Polynucleotides and their Constituents IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (CBN) Accessed 03 Jan 2006

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ghosh A, Bansal M (2003). "A glossary of DNA structures from A to Z". Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 59: 620-6. PMID 12657780.

- ↑ Takahashi I, Marmur J (1963). "Replacement of thymidylic acid by deoxyuridylic acid in the deoxyribonucleic acid of a transducing phage for Bacillus subtilis". Nature 197: 794-5. PMID 13980287.

- ↑ Agris P (2004). "Decoding the genome: a modified view". Nucleic Acids Res 32: 223 – 38. PMID 14715921.

- ↑ Wing R et al. (1980). "Crystal structure analysis of a complete turn of B-DNA". Nature 287: 755 – 8. PMID 7432492.

- ↑ Pabo C, Sauer R. "Protein-DNA recognition". Ann Rev Biochem 53: 293-321. PMID 6236744.

- ↑ Ponnuswamy P, Gromiha M (1994). "On the conformational stability of oligonucleotide duplexes and tRNA molecules". J Theor Biol 169: 419-32. PMID 7526075.

- ↑ Clausen-Schaumann H et al. (2000). "Mechanical stability of single DNA molecules". Biophys J 78: 1997-2007. PMID 10733978.

- ↑ Chalikian T et al. (1999). "A more unified picture for the thermodynamics of nucleic acid duplex melting: a characterization by calorimetric and volumetric techniques". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7853-8. PMID 10393911.

- ↑ deHaseth P, Helmann J (1995). "Open complex formation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: the mechanism of polymerase-induced strand separation of double helical DNA". Mol Microbiol 16: 817-24. PMID 7476180.

- ↑ Isaksson J et al. (2004). "Single-stranded adenine-rich DNA and RNA retain structural characteristics of their respective double-stranded conformations and show directional differences in stacking pattern". Biochemistry 43: 15996-6010. PMID 15609994.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Joyce C, Steitz T (1995). "Polymerase structures and function: variations on a theme?". J Bacteriol 177: 6321-9. PMID 7592405.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Joyce" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Hüttenhofer A et al. (2005). "Non-coding RNAs: hope or hype?". Trends Genet 21: 289-97. PMID 15851066.

- ↑ Munroe S (2004). "Diversity of antisense regulation in eukaryotes: multiple mechanisms, emerging patterns". J Cell Biochem 93: 664-71. PMID 15389973.

- ↑ Makalowska I et al. (2005). "Overlapping genes in vertebrate genomes". Comput Biol Chem 29: 1 – 12. PMID 15680581.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Johnson Z, Chisholm S (2004). "Properties of overlapping genes are conserved across microbial genomes". Genome Res 14: 2268 – 72. PMID 15520290.

- ↑ Lamb R, Horvath C (1991). "Diversity of coding strategies in influenza viruses". Trends Genet 7: 261 – 6. PMID 1771674.

- ↑ Davies J, Stanley J (1989). "Geminivirus genes and vectors". Trends Genet 5: 77 – 81. PMID 2660364.

- ↑ Berns K (1990). "Parvovirus replication". Microbiol Rev 54 (3): 316 – 29. PMID 2215424.

- ↑ Benham C, Mielke S. "DNA mechanics". Annu Rev Biomed Eng 7: 21 – 53. PMID 16004565.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Wang J (2002). "Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 430 – 40. PMID 12042765.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Hayashi G et al. (2005). "Application of L-DNA as a molecular tag". Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 49: 261-2. PMID 17150733.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Hayashi2005" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Vargason JM et al. (2000). "The extended and eccentric E-DNA structure induced by cytosine methylation or bromination". Nat Struct Biol 7: 758-61. PMID 10966645.

- ↑ Wang G, Vasquez KM (2006). "Non-B DNA structure-induced genetic instability". Mutat Res 598: 103-19. PMID 16516932.

- ↑ Palecek E (1991). "Local supercoil-stabilized DNA structures". Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 26: 151-226. PMID 1914495.

- ↑ Basu H et al. (1988). "Recognition of Z-RNA and Z-DNA determinants by polyamines in solution: experimental and theoretical studies". J Biomol Struct Dyn 6: 299-309. PMID 2482766.

- ↑ Wahl M, Sundaralingam M (1997). "Crystal structures of A-DNA duplexes". Biopolymers 44: 45 – 63. PMID 9097733.

- ↑ Lu XJ, Shakked Z, Olson WK (2000). "A-form conformational motifs in ligand-bound DNA structures". J. Mol. Biol. 300 (4): 819-40. PMID 10891271.

- ↑ Rothenburg S, Koch-Nolte F, Haag F. "DNA methylation and Z-DNA formation as mediators of quantitative differences in the expression of alleles". Immunol Rev 184: 286 – 98. PMID 12086319.

- ↑ Oh D et al. (2002). "Z-DNA-binding proteins can act as potent effectors of gene expression in vivo". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 16666-71. PMID 12486233.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Greider C, Blackburn E (1985). "Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts". Cell 43: 405-13. PMID 3907856.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Nugent C, Lundblad V (1998). "The telomerase reverse transcriptase: components and regulation". Genes Dev 12: 1073-85. PMID 9553037.

- ↑ Wright W et al. (1997). "Normal human chromosomes have long G-rich telomeric overhangs at one end". Genes Dev 11: 2801-9. PMID 9353250.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Burge S et al. (2006). "Quadruplex DNA: sequence, topology and structure". Nucleic Acids Res 34: 5402-15. PMID 17012276.

- ↑ Parkinson G et al. (2002). "Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA". Nature 417: 876-80. PMID 12050675.

- ↑ Griffith J et al. (1999). "Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop". Cell 97: 503-14. PMID 10338214.

- ↑ Klose R, Bird A (2006). "Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators". Trends Biochem Sci 31 (2): 89 – 97. PMID 16403636.

- ↑ Bird A (2002). "DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory". Genes Dev 16 (1): 6 – 21. PMID 11782440.

- ↑ Walsh C, Xu G. "Cytosine methylation and DNA repair". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 301: 283 – 315. PMID 16570853.

- ↑ Ratel D et al. (2006). "N6-methyladenine: the other methylated base of DNA". Bioessays 28: 309 – 15. PMID 16479578.

- ↑ Gommers-Ampt J et al. (1993). "beta-D-glucosyl-hydroxymethyluracil: a novel modified base present in the DNA of the parasitic protozoan T. brucei". Cell 75: 1129 – 36. PMID 8261512.

- ↑ Douki T et al. (2003). "Bipyrimidine photoproducts rather than oxidative lesions are the main type of DNA damage involved in the genotoxic effect of solar UVA radiation". Biochemistry 42: 9221-6. PMID 12885257.

- ↑ Cadet J et al. (1999). "Hydroxyl radicals and DNA base damage". Mutat Res 424 (1-2): 9-21. PMID 10064846.

- ↑ Shigenaga M et al. (1989). "Urinary 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine as a biological marker of in vivo oxidative DNA damage". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 9697-701. PMID 2602371.

- ↑ Cathcart R et al. (1984). "Thymine glycol and thymidine glycol in human and rat urine: a possible assay for oxidative DNA damage". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 5633-7. PMID 6592579.

- ↑ Valerie K, Povirk L (2003). "Regulation and mechanisms of mammalian double-strand break repair". Oncogene 22: 5792-812. PMID 12947387.

- ↑ Braña M et al. (2001). "Intercalators as anticancer drugs". Curr Pharm Des 7: 1745-80. PMID 11562309.

- ↑ Ferguson L, Denny W (1991). "The genetic toxicology of acridines". Mutat Res 258: 123-60. PMID 1881402.

- ↑ Jeffrey A (1985). "DNA modification by chemical carcinogens". Pharmacol Ther 28: 237-72. PMID 3936066.

- ↑ Braña M, Cacho M, Gradillas A, de Pascual-Teresa B, Ramos A (2001). "Intercalators as anticancer drugs". Curr Pharm Des 7 (17): 1745 – 80. PMID 11562309.

- ↑ Albà M (2001). "Replicative DNA polymerases". Genome Biol 2: REVIEWS3002. PMID 11178285.

- ↑ Thanbichler M et al. (2005). "The bacterial nucleoid: a highly organized and dynamic structure". J Cell Biochem 96: 506–21. PMID 15988757.

- ↑ Venter J, et al. (2001). "The sequence of the human genome". Science 291: 1304-51. PMID 11181995.

- ↑ Wolfsberg T et al. (2001). "Guide to the draft human genome". Nature 409 (6822): 824-6. PMID 11236998.

- ↑ Gregory T (2005). "The C-value enigma in plants and animals: a review of parallels and an appeal for partnership". Ann Bot (Lond) 95: 133-46. PMID 15596463.

- ↑ Pidoux A, Allshire R (2005). "The role of heterochromatin in centromere function". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360 (1455): 569-79. PMID 15905142.

- ↑ Harrison P et al. (2002). "Molecular fossils in the human genome: identification and analysis of the pseudogenes in chromosomes 21 and 22". Genome Res 12: 272-80. PMID 11827946.

- ↑ Harrison P, Gerstein M (2002). "Studying genomes through the aeons: protein families, pseudogenes and proteome evolution". J Mol Biol 318: 1155-74. PMID 12083509.

- ↑ Sandman K, Pereira S, Reeve J (1998). "Diversity of prokaryotic chromosomal proteins and the origin of the nucleosome". Cell Mol Life Sci 54: 1350-64. PMID 9893710.

- ↑ Luger K et al. (1997). "Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution". Nature 389: 251-60. PMID 9305837.

- ↑ Jenuwein T, Allis C (2001). "Translating the histone code". Science 293: 1074-80. PMID 11498575.

- ↑ Ito T. "Nucleosome assembly and remodelling". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 274: 1-22. PMID 12596902.

- ↑ Thomas J (2001). "HMG1 and 2: architectural DNA-binding proteins". Biochem Soc Trans 29: 395-401. PMID 11497996.

- ↑ Grosschedl R, Giese K, Pagel J (1994). "HMG domain proteins: architectural elements in the assembly of nucleoprotein structures". Trends Genet 10: 94-100. PMID 8178371.

- ↑ Iftode C et al. (1999). "Replication protein A (RPA): the eukaryotic SSB". Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 34: 141-80. PMID 10473346.

- ↑ Myers L, Kornberg R. "Mediator of transcriptional regulation". Annu Rev Biochem 69: 729-49. PMID 10966474.

- ↑ Spiegelman B, Heinrich R (2004). "Biological control through regulated transcriptional coactivators". Cell 119: 157-67. PMID 15479634.

- ↑ Li Z et al. (2003). "A global transcriptional regulatory role for c-Myc in Burkitt's lymphoma cells". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8164-9. PMID 12808131.

- ↑ Pabo C, Sauer R. "Protein-DNA recognition". Annu Rev Biochem 53: 293-321. PMID 6236744.

- ↑ Bickle T, Krüger D (1993). "Biology of DNA restriction". Microbiol Rev 57 (2): 434 – 50. PMID 8336674.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Doherty A, Suh S (2000). "Structural and mechanistic conservation in DNA ligases.". Nucleic Acids Res 28 (21): 4051 – 8. PMID 11058099.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChampoux - ↑ Schoeffler A, Berger J (2005). "Recent advances in understanding structure-function relationships in the type II topoisomerase mechanism". Biochem Soc Trans 33 (Pt 6): 1465 – 70. PMID 16246147.

- ↑ Tuteja N, Tuteja R (2004). "Unraveling DNA helicases. Motif, structure, mechanism and function". Eur J Biochem 271 (10): 1849–63. PMID 15128295.

- ↑ Hubscher U, Maga G, Spadari S. "Eukaryotic DNA polymerases". Annu Rev Biochem 71: 133 – 63. PMID 12045093.

- ↑ Johnson A, O'Donnell M. "Cellular DNA replicases: components and dynamics at the replication fork". Annu Rev Biochem 74: 283 – 315. PMID 15952889.

- ↑ Tarrago-Litvak L, Andréola M, Nevinsky G, Sarih-Cottin L, Litvak S (1994). "The reverse transcriptase of HIV-1: from enzymology to therapeutic intervention". FASEB J 8 (8): 497–503. PMID 7514143.

- ↑ Martinez E (2002). "Multi-protein complexes in eukaryotic gene transcription". Plant Mol Biol 50 (6): 925 – 47. PMID 12516863.

- ↑ Cremer T, Cremer C (2001). "Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells". Nat Rev Genet 2: 292-301. PMID 11283701.

- ↑ Pál C et al. (2006). "An integrated view of protein evolution". Nat Rev Genet 7: 337-48. PMID 16619049.

- ↑ O'Driscoll M, Jeggo P (2006). "The role of double-strand break repair - insights from human genetics". Nat Rev Genet 7: 45-54. PMID 16369571.

- ↑ Ghosh K, Van Duyne G (2002). "Cre-loxP biochemistry". Methods 28: 374-83. PMID 12431441.

- ↑ Sung, P., Krejci, L., Van Komen, S. and Sehorn, M. G. (2003). "Rad51 recombinase and recombination mediators". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (44): 42729-32. PMID 12912992.

- ↑ Dickman M et al. (2002). "The RuvABC resolvasome". Eur J Biochem 269: 5492-501. PMID 12423347.

- ↑ Collins A, Morton N (1994). "Likelihood ratios for DNA identification". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 6007-11. PMID 8016106.

- ↑ Weir B et al. (1997). "Interpreting DNA mixtures". J Forensic Sci 42: 213-22. PMID 9068179.

- ↑ Jeffreys A et al.. "Individual-specific 'fingerprints' of human DNA.". Nature 316: 76-9. PMID 2989708.

- ↑ Colin Pitchfork - first murder conviction on DNA evidence also clears the prime suspect Forensic Science Service Accessed 23 Dec 2006

- ↑ DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents. National Institute of Justice (September 2006).

- ↑ Baldi, Pierre. Brunak, Soren. Bioinformatics: The Machine Learning Approach MIT Press (2001) ISBN 978-0-262-02506-5

- ↑ Gusfield D (1997) Algorithms on Strings, Trees, and Sequences: Computer Science and Computational Biology. Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-58519-4.

- ↑ Sjölander K (2004). "Phylogenomic inference of protein molecular function: advances and challenges". Bioinformatics 20: 170-9. PMID 14734307.

- ↑ Mount DM (2004). Bioinformatics: Sequence and Genome Analysis, 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0879697121.

Further reading

- Clayton, Julie. (Ed.). 50 Years of DNA, Palgrave MacMillan Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1-40-391479-8

- Judson, Horace Freeland. The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-87-969478-4

- Olby, Robert. The Path to The Double Helix: Discovery of DNA, first published in October 1974 by MacMillan, with foreword by Francis Crick; ISBN 978-0-48-668117-7; the definitive DNA textbook, revised in 1994, with a 9 page postscript.

- Ridley, Matt. Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code (Eminent Lives) first published in June 2006 in the USA and then to be in the UK September 2006, by HarperCollins Publishers; 192 pp, ISBN 978-0-06-082333-7

- Rose, Steven. The Chemistry of Life, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-027273-4.

- Watson, James D. and Francis H.C. Crick. A structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid (PDF). Nature 171, 737 – 738, 25 April 1953.

- Watson, James D. DNA: The Secret of Life ISBN 978-0-375-41546-3.

- Watson, James D. The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (Norton Critical Editions). ISBN 978-0-393-95075-5

External links

- DNA from the beginning

- Double helix: 50 years of DNA, Nature.

- Rosalind Franklin's contributions to the study of DNA.

- U.S. National DNA Day Watch videos and participate in real-time chat with top scientists

- Genetic Education Modules for Teachers DNA from the Beginning Study Guide

- Listen to Francis Crick and James Watson talking on the BBC in 1962, 1972, and 1974

- Using DNA in Genealogical Research

- DNA Interactive (requires Adobe Flash)

- DNA: RCSB PDB Molecule of the Month

- DNA under electron microscope

- DNA Articles DNA Articles and Information collected from various sources.

- DNA coiling to form chromosomes