Pin-up art: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 4 October 2024

Pin-up art is an image of a person sufficiently attractive that a viewer would pin it to a wall, to be enjoyed frequently. "Attractive" implies a sensual, romantic, or erotic quality. Some call it soft-core pornography, but it tends not to fall into the most common usages of that term.

The genre originally involved females, and was also called "cheesecake" as a metaphor for something sweet. With increasing acceptance of female sexuality, the subgenre of "beefcake" — attractive men — emerged. These definitions are heterosexually oriented, and, for other orientations, a pinup would be a person of the opposite gender.

"Pin-up" was first documented in English usage in 1941; however the practice is documented back at least to the 1890s. [1]

One early application of "pin-up" art was in calendars intended to be hung on walls; given the reality that sexual attractiveness makes for effective advertising, commercial pin-up calendars are still common, although workplace rules about sexual harassment has reduced their prevalence.

Precursors

In the United States, the "Gibson Girl" first appeared in 1887, showing idealized attractive women, but Charles Dana Gibson's images were not formatted as pin-ups. [2]

While they were not called pin-ups, advertising posters, featuring attractive women, became common in Paris in the 1890s. These were especially associated with Jules Cheret, and with the relatively new color printing process of three-stone lithography. [3] Cheret's Art Nouveau style did not portray women in the stereotyped "Madonna and whore" roles, but as sexually aware and very alive. He would depict them, especially his favorite model, Loie Fuller, in taboo activities, such as nude dancing at the Folies Bergere, a popular French theatre which inspired “The Ziegfeld Follies”.[4]

Raphael Kirchner produced "pretty girl postcards."

Pre-WWII

While the term "pin-up" was not yet in use, the early 20th century showed a significant increase in images resembling pin-ups, and which were certainly informally pinned to walls. Several factors encouraged this, including changing roles of women and societal tolerance to erotica. Technical improvements in photography and printing made it possible to take images more cheaply and produce large volumes of more realistic copies.

Advertising

At the turn of the 20th century, the calendar was the most prominent form of pin-up material, especially the early "glamour girl" formats by Angelo Asti. In 1913 the controversial nude "September Morn" by Paul Chabas was censored by the New York Society for the Supression of Vice. Still, the image was subsequently printed on literally hundreds of thousands of calendars, in addition to candy boxes, postcards and more. The Art Deco period also made respectable any art featuring Romantic nudity, such as the work of Maxfield Parrish. [1]

Magazine

One of the early large-circulation magazines to use pin-ups, usually of women appropriate to the affluent male target audience, was Esquire. It used both artwork and photographs; the best-known early artist was George Petty, although he was later replaced by Alberto Vargas, who was less expensive and then less well known.

Esquire introduced the precursor of today's magazine "foldout", beginning with images spread across two facing pages. It eventually introduced a three-page version.

Second World War

Photographs, and printed versions of photographs, became more common, although paintings and drawings were still important. Soldiers of most countries kept pin-ups, corresponding to their culture's idea of attractiveness. Betty Grable's photograph was among the most popular for Americans.

A variant of the pin-up was nose art, or paintings on the noses of warplanes. These were frequently of attractive women, although could be of almost anything; dragons and sharks were common martial images. The images of women could be of a cartoon style or quite realistic, at least in contemporary pin-up terms.

Postwar

Both commercial and fine art pin-up art flourished, and the genre even extended into social comment and politics.

Commercial

Commercial pin-ups increasingly challenged limits. Playboy magazine moved well beyond Esquire in December 1953, printing a foldout that showed bare breasts, and suggesed full nudity but did not display genitalia. It welcomed Vargas and other skilled non-photographic artists, while interviews with its photographers and photo editors were studied in serious photography magazines. It evoked both moral condemnation and great sales.

In response, Penthouse began to compete with Playboy, by going further in the sexuality of its pictures. It was the first to show pubic hair, and then full genitalia; it later included things frequently considered hard-core pornography involving overt sexual acts. Still, Penthouse photographs maintained high artistic quality; the competitor, Hustler, was as or more explicit, but in a more blatant style.

Fine art

New generations of artists, inspired by Vargas and other path-setters, both extended their style and created their own. While Olivia de Berardinis has a monthly image Her work appears monthly in Playboy, for which publisher Hugh Hefner, whom she regards as a patron, but she also has one-woman gallery exhibitions and publishes limited edition prints and art books. She cites Enoch Boles, George Petty and Alberto Vargas as his inspirations with their pin-up work.

Both style, and technique using such media as airbrush, have moved from the soft-focus style of Vargas to much more photorealistic imagery, as with Hajime Sorayama.

Social and political

Recent pinups have moved into social protest politics.

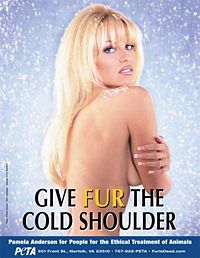

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has run an extensive advertising series with sympathetic celebrities posing nude for under the general theme "I'd rather go naked than wear fur."

While G. Gordon Liddy is a well-known although iconoclastic American conservative, he has used patriotism, guns, and attractive women to produce what he terms the world's "Most Politically Incorrect" commercial calendar. In 2004, he commented that he In an exclusive New Year's Day interview Liddy told Talon News he was motivated to create the calendar to raise money for charity and "put a stick in the eye of the liberals who were upset that I was on the air." He consciously attacked political correctness. "When I was a kid during World War II, every garage and machine shop had a pin-up calendar...We started with a girlie calendar." To show his support of gun rights, the next calendar would have "all of the models would be holding firearms, especially if we can get fully automatic weapons." In one more way to antagonize liberals "To make it complete, this year each of the models will be posed with motorcycles, the last unregulated internal combustion engine left." Liddy himself appears on the cover with his own Harley-Davidson and gun along with his naked executive producer. [5]

The 10th, 2010 edition is

13 months of Dangerous Dames, Femme Fatales and Beautiful Betties armed with classic machine guns, rifles, pistols and shotguns that won WWII for the Allies and made the 1930s roar. It is a fitting tribute to the Second Amendment, Beautiful Women and America at its best.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The History of Pin-Up Art, The Art History Archive - Erotica

- ↑ The Gibson Girl: The Ideal Woman of the Early 1900s, EyeWitness to History, 2001

- ↑ Jim Burrows, Origins of Cheesecake, Cheesecake and The Art of the Pin-up

- ↑ Annie Samuelson (2 February 2009), Movement, Color and Sexual Undertones in Depictions of Women through Art

- ↑ Liddy Comes Under Fire for Racy Calendar, Talon News, 12 January 2004

- ↑ The World's "Most Politically Incorrect" Stacked and Packed 2010 Calendar, G. Gordon Liddy