PH: Difference between revisions

imported>Peter Schmitt (→Formal definition: some copy edits) |

imported>Milton Beychok m (Re-wrote and re-formatted the article. Still need more sections. See Talk page.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{lowercase|title=pH}}{{subpages}} | {{lowercase|title=pH}}{{subpages}} | ||

The | {{Image|PH scale.png|right|281px|The pH scale}} | ||

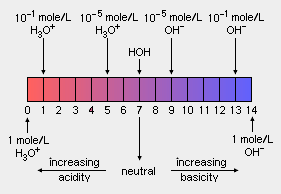

The '''pH''' scale measures the [[acid]]ity or [[alkalinity]] of an aqueous solution. Values for pH range from 0 (strongly acidic) to 14 (strongly alkaline or basic). The pH of a neutral solution (neither acid or basic), such as pure [[water]] at room [[temperature]] and atmospheric [[pressure]] is 7, whereas the pH of an acidic solution is less than 7 and the pH of a basic solution is greater than 7. The pH scale is [[logarithm]]ic which means that a difference of one pH unit is equivalent to a ten-fold difference in hydrogen ion concentration. The notation '''pH''' is sometimes referred to as the '''''power of hydrogen''''' or the '''''potential of hydrogen'''''. | |||

The | The traditional way to determine whether a solution is acidic or basic is by wetting [[litmus paper]] with the solution. If the wet litmus paper turns red, the solution has a pH less than 7 and is acidic. If it turns blue, the solution has a pH greater than 7 and is acidic. Measuring the actual pH value of a solution is more accurately done with a [[pH meter]]. | ||

== | The pH scale was originally defined by [[Denmark|Danish]] biochemist [[Søren Peter Lauritz Sørensen]] in 1909, who wrote it as P<sub>H</sub>. It was subsequently changed to the modern notation of pH in 1920 by [[William Mansfield Clark]], an [[United States|American]] biochemist, for typographical convenience in his book ''The Determination of Hydrogen Ions''.<ref>{{cite book|author=William Mansfield Clark|title=The Determination of Hydrogen Ions|edition=1st Edition|publisher=William & Wilkins Company|year=1920|pages=page 35|id=}} Available in Google Books [http://books.google.com/books?id=spsLAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=&f=false here]</ref><ref>[http://science.jrank.org/pages/49372/pH.html pH: Potenz, The Determination of Hydrogen Ions, History of Analytical Chemistry, Electrochemistry, Past and Present] From the JRank Science & Philosophy website</ref> | ||

==Definitions and discussion== | |||

{| border=0 width=300 align=right cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0 style="wrap=no" | |||

| | |||

{|class=wikitable border=1 align=right | |||

|+ H<sup>+</sup> and OH<sup>-</sup> ions<br/>molar concentrations vs. pH | |||

!H<sup>+</sup> concentration<br/>(mole/litre!!OH<sup>-</sup> concentration<br/>(mole/litre)!!pH | |||

|- | |||

|1||0.00000000000001||align=center|0 | |||

|- | |||

|0.1||0.0000000000001||align=center|1 | |||

|- | |||

|0.01||0.000000000001||align=center|2 | |||

|- | |||

|0.001||0.00000000001||align=center|3 | |||

|- | |||

|0.0001||0.0000000001||align=center|4 | |||

|- | |||

|0.00001||0.000000001||align=center|5 | |||

|- | |||

|0.000001||0.00000001||align=center|6 | |||

|- style="background:teal; color:white" | |||

|0.0000001||0.0000001||align=center|7 | |||

|- | |||

|0.00000001||0.000001||align=center|8 | |||

|- | |||

|0.000000001||0.00001||align=center|9 | |||

|- | |||

|0.0000000001||0.0001||align=center|10 | |||

|- | |||

|0.00000000001||0.001||align=center|11 | |||

|- | |||

|0.000000000001||0.01||align=center|12 | |||

|- | |||

|0.0000000000001||0.1||align=center|13 | |||

|- | |||

|0.00000000000001||1||align=center|14 | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

{{main|Activity (chemistry)|Activity coefficient}} | |||

The [[Molarity|molar]] [[Concentration (chemistry)|concentration]], in [[Mole (unit)|moles]] per [[litre]] of solution, of [[hydrogen]] (H<sup>+</sup>) [[ion]]s in an aqueous solution can be written simply as '''[H<sup>+</sup>]''' or as hydronium '''[H<sub>3</sub>O<sup>+</sup>]''' and both describe the same entity. | |||

For very dilute solutions, the pH value can be defined by this simple expression:<ref>{{cite book|author=Darrell D. Ebbing and Mark S. Wrighton|title=General Chemistry|edition=2nd Edition|publisher=Houghton Mifflin|year=1987|pages=pp. 103-117|id=ISBN 0-395-35654-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Kenneth W. Whitten and Kenneth D. Gailey|title=General Chemistry with Qualitative Analysis|edition=2nd Edition|publisher=Saunders College|year=1984|pages=pp. 263-278|id=ISBN 0-03-63287-5}}</ref> | |||

: <math> \left[\rm | :'''(1)''' <math>{\rm pH} = -\log_{10} \left[\rm H^+ \right] = \log_{10} \frac{1}{\left[\rm H^+ \right]}</math> | ||

and the corresponding expression for the [[hydroxide]] (OH<sup>-</sup>) ions can be expressed as: | |||

: <math> \ | :'''(2)''' <math>{\rm POH} = -\log_{10} \left[\rm OH^- \right] = \log_{10} \frac{1}{\left[\rm OH^- \right]}</math> | ||

Since the product of the concentration of hydrogen ions and the concentration of hydroxide ions is a constant, namely: | |||

: <math> \ | :'''(3)''' <math>\left[\rm H^+ \right] \left[\rm OH^- \right] = 1 \times 10^{-14}</math> | ||

taking logarithms gives: | |||

< | :'''(4)''' <math>\left({\rm pH} + {\rm pOH} \right) = 14</math> | ||

< | |||

< | The mid-point of 7 in the pH scale indicates ionic neutrality of the solution, namely when [H<sub>+</sub>] equals [OH<sub>-</sub>] (see the adjacent table). | ||

< | |||

< | As the theory behind [[chemical reaction]]s became more sophisticated, the definition of pH was reexamined. Specifically, as the role of electrical charge in chemical reactions became better understood, the definition of pH was changed to refer to the active hydrogen ion concentration. The more theoretical definition of pH, while not generally covered in many introductory chemistry textbooks, is the definition adopted by the [[International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry]] (IUPAC):<ref name=Finesse>[http://finesse.com/files/pdfs/app-tech-notes/Finesse.TrupH.MeasureDef.pdf pH Measurement Definitions: The pH Scale]</ref><ref name=IUPAC>[http://goldbook.iupac.org/P04524.html IUPAC Gold Book: pH]</ref> | ||

< | |||

:'''(5)''' <math>{\rm pH} = - \log_{10}\,(a_{\rm H^+}) = \log_{10}\,\left( \gamma\, \left[\rm H^+ \right] \right )</math> | |||

where <math>a_{\rm H^+}</math> is the hydrogen ion [[activity (chemistry)|activity]] and <math>\gamma</math> is the hydrogen ion [[activity coefficient]].<ref name=Finesse/><ref name=IUPAC/> | |||

Only in dilute solutions (about 0.001 moles per litre or less) are all anion and cations so far apart that they are free to be at their maximum activity where: | |||

:'''(6)''' <math>\gamma = 1</math> and thus <math>a_{\rm H^+}= \left[\rm H^+ \right]</math> | |||

At higher [[acid]] and [[Base (chemistry)|base]] concentrations, the space between cations and anions decreases, so that they begin to obstruct each other and shield each other’s charge. Thus, the mobility of the any particular ion is impaired by interactions with other ions and their associated electrical fields. These local electric field interactions affect the extent to which the ions can participate in chemical reactions, and give an apparent concentration that is always smaller than the real concentration. In other words, the ion activity is "slowed down" and '''[H<sup>+</sup>]''' becomes greater than '''''a'''''<sub>'''H'''<sup>'''+'''</sup></sub>. This difference between ion activity and concentration increases with the increasing acid concentration. Therefore, for acid concentrations greater than about 0.001 moles per litre, it is advisable to use activities instead of concentrations in order to accurately predict pH.<ref name=Finesse/> | |||

==pH of some common substances== | |||

The two tables below list the pH ranges for each of a number of fairly common substances: | |||

{|align=center | |||

| | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|- | |||

!Substance !! pH | |||

|- | |||

| Human gastric juice | |||

| align="center"| 1.0 − 3.0 | |||

|- | |||

| Car battery acid | |||

| align="center"| 1.1 − 1.7 | |||

|- | |||

| Lime juice | |||

| align="center"| 1.8 − 2.0 | |||

|- | |||

| Soft drinks | |||

| align="center"| 2.0 − 4.0 | |||

|- | |||

| Lemon juice | |||

| align=center| 2.2 − 2.4 | |||

|- | |||

| Vinegar | |||

| align="center"| 2.4 − 3.4 | |||

|- | |||

| Apple juice | |||

| align="center"| 2.9 − 3.3 | |||

|- | |||

| Wine | |||

| align="center"| 3.4 − 3.7 | |||

|- | |||

| Tomato juice | |||

| align="center"| 4.0 − 4.4 | |||

|- | |||

| Beer | |||

| align="center"| 4.0 − 5.0 | |||

|- | |||

| Rainwater | |||

| align="center"| 5.1 − 5.6 | |||

|} | |||

| | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

| | |||

|} | |||

| | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|- | |||

!Substance !! pH | |||

|- | |||

| Banana juice | |||

| align="center"| 4.5 − 4.7 | |||

|- | |||

| Human urine | |||

| align="center"| 4.8 − 8.4 | |||

|- | |||

| Cow milk | |||

| align="center"| 6.3 − 6.6 | |||

|- | |||

| Human saliva | |||

| align="center"| 6.5 − 7.5 | |||

|- | |||

| Human blood plasma | |||

| align="center"| 7.3 − 7.5 | |||

|- | |||

| Sea water | |||

| align="center"| 7.4 − 8.3 | |||

|- | |||

| Egg white | |||

| align="center"| 7.6 − 8.0 | |||

|- | |||

| Baking soda solution | |||

| align="center"| 8.3 − 8.8 | |||

|- | |||

| Milk of Magnesia | |||

| align="center"|10.6 − 10.7 | |||

|- | |||

| Household ammonia | |||

| align="center"| 11.0 − 12.0 | |||

|- | |||

| Household lye | |||

| align="center"| 13.6 − 14.0 | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

Revision as of 19:30, 14 February 2010

The pH scale measures the acidity or alkalinity of an aqueous solution. Values for pH range from 0 (strongly acidic) to 14 (strongly alkaline or basic). The pH of a neutral solution (neither acid or basic), such as pure water at room temperature and atmospheric pressure is 7, whereas the pH of an acidic solution is less than 7 and the pH of a basic solution is greater than 7. The pH scale is logarithmic which means that a difference of one pH unit is equivalent to a ten-fold difference in hydrogen ion concentration. The notation pH is sometimes referred to as the power of hydrogen or the potential of hydrogen.

The traditional way to determine whether a solution is acidic or basic is by wetting litmus paper with the solution. If the wet litmus paper turns red, the solution has a pH less than 7 and is acidic. If it turns blue, the solution has a pH greater than 7 and is acidic. Measuring the actual pH value of a solution is more accurately done with a pH meter.

The pH scale was originally defined by Danish biochemist Søren Peter Lauritz Sørensen in 1909, who wrote it as PH. It was subsequently changed to the modern notation of pH in 1920 by William Mansfield Clark, an American biochemist, for typographical convenience in his book The Determination of Hydrogen Ions.[1][2]

Definitions and discussion

|

The molar concentration, in moles per litre of solution, of hydrogen (H+) ions in an aqueous solution can be written simply as [H+] or as hydronium [H3O+] and both describe the same entity.

For very dilute solutions, the pH value can be defined by this simple expression:[3][4]

- (1)

and the corresponding expression for the hydroxide (OH-) ions can be expressed as:

- (2)

Since the product of the concentration of hydrogen ions and the concentration of hydroxide ions is a constant, namely:

- (3)

taking logarithms gives:

- (4)

The mid-point of 7 in the pH scale indicates ionic neutrality of the solution, namely when [H+] equals [OH-] (see the adjacent table).

As the theory behind chemical reactions became more sophisticated, the definition of pH was reexamined. Specifically, as the role of electrical charge in chemical reactions became better understood, the definition of pH was changed to refer to the active hydrogen ion concentration. The more theoretical definition of pH, while not generally covered in many introductory chemistry textbooks, is the definition adopted by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC):[5][6]

- (5)

where is the hydrogen ion activity and is the hydrogen ion activity coefficient.[5][6]

Only in dilute solutions (about 0.001 moles per litre or less) are all anion and cations so far apart that they are free to be at their maximum activity where:

- (6) and thus

At higher acid and base concentrations, the space between cations and anions decreases, so that they begin to obstruct each other and shield each other’s charge. Thus, the mobility of the any particular ion is impaired by interactions with other ions and their associated electrical fields. These local electric field interactions affect the extent to which the ions can participate in chemical reactions, and give an apparent concentration that is always smaller than the real concentration. In other words, the ion activity is "slowed down" and [H+] becomes greater than aH+. This difference between ion activity and concentration increases with the increasing acid concentration. Therefore, for acid concentrations greater than about 0.001 moles per litre, it is advisable to use activities instead of concentrations in order to accurately predict pH.[5]

pH of some common substances

The two tables below list the pH ranges for each of a number of fairly common substances:

|

|

|

References

- ↑ William Mansfield Clark (1920). The Determination of Hydrogen Ions, 1st Edition. William & Wilkins Company, page 35. Available in Google Books here

- ↑ pH: Potenz, The Determination of Hydrogen Ions, History of Analytical Chemistry, Electrochemistry, Past and Present From the JRank Science & Philosophy website

- ↑ Darrell D. Ebbing and Mark S. Wrighton (1987). General Chemistry, 2nd Edition. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 103-117. ISBN 0-395-35654-7.

- ↑ Kenneth W. Whitten and Kenneth D. Gailey (1984). General Chemistry with Qualitative Analysis, 2nd Edition. Saunders College, pp. 263-278. ISBN 0-03-63287-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 pH Measurement Definitions: The pH Scale

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 IUPAC Gold Book: pH

![{\displaystyle {\rm {pH}}=-\log _{10}\left[{\rm {H^{+}}}\right]=\log _{10}{\frac {1}{\left[{\rm {H^{+}}}\right]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/976cd17230bab93ec437fce0bc287f9d5423381f)

![{\displaystyle {\rm {POH}}=-\log _{10}\left[{\rm {OH^{-}}}\right]=\log _{10}{\frac {1}{\left[{\rm {OH^{-}}}\right]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f32a06e043994609d484488623cf55e8106188f6)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\rm {H^{+}}}\right]\left[{\rm {OH^{-}}}\right]=1\times 10^{-14}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/325d636951f2777f518ef1c863aa20753c214bea)

![{\displaystyle {\rm {pH}}=-\log _{10}\,(a_{\rm {H^{+}}})=\log _{10}\,\left(\gamma \,\left[{\rm {H^{+}}}\right]\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/63da3c5dac9bc6e9a1daa1ba102dd1f3c4b34bcc)

![{\displaystyle a_{\rm {H^{+}}}=\left[{\rm {H^{+}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/036389b0aca36a256c21fe79646f187457aa76f4)