User:David MacQuigg/Sandbox/Anycasting: Difference between revisions

imported>David MacQuigg No edit summary |

imported>David MacQuigg No edit summary |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

'''Anycasting''' is an Internet Protocol routing technique in which the same [[IP address]] may exist at several points in the network, with the caveat that each instance of the address must provide exactly the same services. While the term anycast came into prominence with [[IPv6]] work,<ref name=RFC4291>{{citation | This is a draft version in which I have added lots of editorial footnotes, to be deleted in the finished version. I'm following Einstein's rule here - Make things as simple as possible, but no simpler. I'm not an expert in routing. Tell me if I've made any of this too simple. --[[User:David MacQuigg|David MacQuigg]] 17:34, 16 October 2009 (UTC) | ||

'''Anycasting''' is an Internet Protocol routing technique in which the same [[IP address]] may exist at several points in the network, with the caveat that each instance of the address must provide exactly the same services. The technique is useful for load balancing, fault tolerance, and security against a [[Denial of service|DoS]] attack. | |||

A typical application is a heavily-used database like DNS, where the same data can be provided from any number of identical servers. Applications are not limited to "read-only" however. See the [[Sinkhole|sinkholes]] operational example below. | |||

Traditionally, an IP address needed to be unique. This would be absolutely true in a single network with no segmentation. The Internet, however, is a collection of networks linked by routers. When the same address is claimed by servers on different networks, an upstream router simply assumes it is the same server as seen via different routes. It picks the shortest path for its routing table, and ignores the rest. A router supporting anycast keeps these routes available as alternatives. Alternative routes may be selected randomly, in a cyclic pattern, or depending on external factors, such as the current load reported by each server. | |||

While the term anycast came into prominence with [[IPv6]] work,<ref name=RFC4291>{{citation | |||

| id = RFC 4291 | | id = RFC 4291 | ||

| title = IP Version 6 Addressing Architecture. | | title = IP Version 6 Addressing Architecture. | ||

| first1 =R.|last1=Hinden |first2= S. | last2=Deering. | | first1 = R.|last1=Hinden |first2=S.|last2=Deering. | ||

| date = February 2006 | | date = February 2006}}</ref> it can be quite useful with IPv4. IPv4 has no infrastructure explicitly for anycast while IPv6 does, but the technique can be applied in both areas, with different address structures. Miller discusses "shared anycast",<ref name=>{{citation | ||

| url = http://www.net.cmu.edu/pres/anycast/Deploying%20IP%20Anycast.ppt | | url = http://www.net.cmu.edu/pres/anycast/Deploying%20IP%20Anycast.ppt | ||

| title = Deploying IP Anycast | | title = Deploying IP Anycast | ||

| first1 = Kevin | last1 = Miller | | first1 = Kevin | last1 = Miller | ||

| date = NANOG 29 – October 2003}}</ref> which is different from the IPv6 specific work in <nowiki>RFC 4291</nowiki>, which superseded the <nowiki>RFC 3513</nowiki> mentioned in the Miller paper. | | date = NANOG 29 – October 2003}}</ref> which is different from the IPv6 specific work in <nowiki>RFC 4291</nowiki>, which superseded the <nowiki>RFC 3513</nowiki> mentioned in the Miller paper. | ||

The IPv6 architecture describes it as: | The IPv6 architecture describes it as: | ||

| Line 20: | Line 22: | ||

==Contrast to multicast== | ==Contrast to multicast== | ||

[[Multicasting]] | Anycasting is similar to [[Multicasting]]. In multicasting, a source '''S''' sends to a group '''G''' of recipients. Broadcasting is a special case where '''G''' contains all possible recipients. It is assumed that '''G''' has more than one member. | ||

An anycast source '''S''' sends to a destination address '''D''', which '''S''' believes to be a single | An anycast source '''S''' sends a data packet to a destination address '''D''', which '''S''' believes to be a single machine. In reality, there are multiple instances of '''D''', any one of which can receive the packet addressed to '''D'''. | ||

{{Image|Anycast-Load-Distribution.png|right|300px|Load distribution example}} | {{Image|Anycast-Load-Distribution.png|right|300px|Figure 1. Load distribution example}} | ||

==Load balancing case== | ==Load balancing case== | ||

In | In Figure 1, there are two clients and three servers, all with the same IP address 3.1.1.1. It makes no difference to either client which server satisfies its request. | ||

The | The traditional routing algorithm adds up the costs of links along the available routes to a destination and always picks the lowest cost route. From client '''1''', server '''A''' is closest (cost=1) and server '''3''' is furthest (cost=3). Therefore, client '''1''' always connects to server '''A''', and client 2 always connects to server '''C'''. | ||

{{Image|Anycast-before-failure.png|right|300px|Single client with all servers working}} | |||

An anycast router can balance the load among all routes, rapidly switching from one to another. A packet from Client 1 can be routed just as easily to Server C as to Server A.<ref> | |||

The figure raises a question. Do we have to assume all the routers in a load-balancing setup are anycast? Should we answer this question or change the figure? | |||

</ref> | |||

{{Image|Anycast-before-failure.png|right|300px|Figure 2. Single client with all servers working}} | |||

==Fault tolerance case== | ==Fault tolerance case== | ||

Now, simplify the scenario to have but one | Now, simplify the scenario to have but one client (Figure 2). As long as server '''A''' is up, router '''1''' will see a cost of 1 to reach server '''A'''. The routing process was aware of other routes to 3.1.1.1, but there was a cost of 2 to server '''B''' and a cost of 3 to server '''C'''. Router '''1''' put only the lowest-cost route into its routing table. | ||

{{Image|Anycast-after-failure.png|right|300px|Single client after failure}} | {{Image|Anycast-after-failure.png|right|300px|Figure 3. Single client after failure}} | ||

But what if server '''A''' fails? The router knows other paths to the same address, so it will install the path that goes through router '''2'''. The client will still receive exactly the same service from exactly the same address. | But what if server '''A''' fails? The router knows other paths to the same address, so it will install the path that goes through router '''2'''. The client will still receive exactly the same service from exactly the same address.<ref> | ||

Isn't this how a traditional router works? Why do we need anycast for fault tolerance? | |||

</ref> | |||

==Operational examples== | |||

Anycast works well for applications that do not require perfect synchronization of changes at the servers and do not need to keep track of sessions or user state. An application requiring the user to log in, for example, might get confused if the session was suddenly switched to a machine on which the user is not logged in. | |||

One common application of anycast is the root servers for the [[Domain Name System]]. While the official list has thirteen named servers, there are actually hundreds of geographically distributed machines. | |||

Another application is an active defense against [[Denial of service|DoS]] attacks. Instead of just providing more capacity to absorb the attack, or even [[null-routing]] it, it is possible to divert the attack to a set of [[Sinkhole|sinkholes]] that analyze the traffic, and perhaps even engage with the attacker, trying to elicit traceback information, or even [[tarpit]] the attacker's machines. | |||

When an attack is detected, the server under attack would be useless due to overload, so its address is reassigned as an anycast address of a set of sinkholes. For a single-stream attack, the sinkhole nearest the ingress router does the analysis. For a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, the entire set of sinkholes may engage. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

Latest revision as of 05:28, 17 October 2009

This is a draft version in which I have added lots of editorial footnotes, to be deleted in the finished version. I'm following Einstein's rule here - Make things as simple as possible, but no simpler. I'm not an expert in routing. Tell me if I've made any of this too simple. --David MacQuigg 17:34, 16 October 2009 (UTC)

Anycasting is an Internet Protocol routing technique in which the same IP address may exist at several points in the network, with the caveat that each instance of the address must provide exactly the same services. The technique is useful for load balancing, fault tolerance, and security against a DoS attack. A typical application is a heavily-used database like DNS, where the same data can be provided from any number of identical servers. Applications are not limited to "read-only" however. See the sinkholes operational example below.

Traditionally, an IP address needed to be unique. This would be absolutely true in a single network with no segmentation. The Internet, however, is a collection of networks linked by routers. When the same address is claimed by servers on different networks, an upstream router simply assumes it is the same server as seen via different routes. It picks the shortest path for its routing table, and ignores the rest. A router supporting anycast keeps these routes available as alternatives. Alternative routes may be selected randomly, in a cyclic pattern, or depending on external factors, such as the current load reported by each server.

While the term anycast came into prominence with IPv6 work,[1] it can be quite useful with IPv4. IPv4 has no infrastructure explicitly for anycast while IPv6 does, but the technique can be applied in both areas, with different address structures. Miller discusses "shared anycast",[2] which is different from the IPv6 specific work in RFC 4291, which superseded the RFC 3513 mentioned in the Miller paper.

The IPv6 architecture describes it as:

Anycast: An identifier for a set of interfaces (typically belonging to different nodes). A packet sent to an anycast address is delivered to one of the interfaces identified by that address (the "nearest" one, according to the routing protocols' measure of distance).[1]

Contrast to multicast

Anycasting is similar to Multicasting. In multicasting, a source S sends to a group G of recipients. Broadcasting is a special case where G contains all possible recipients. It is assumed that G has more than one member.

An anycast source S sends a data packet to a destination address D, which S believes to be a single machine. In reality, there are multiple instances of D, any one of which can receive the packet addressed to D.

Load balancing case

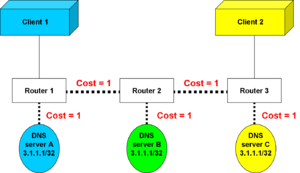

In Figure 1, there are two clients and three servers, all with the same IP address 3.1.1.1. It makes no difference to either client which server satisfies its request.

The traditional routing algorithm adds up the costs of links along the available routes to a destination and always picks the lowest cost route. From client 1, server A is closest (cost=1) and server 3 is furthest (cost=3). Therefore, client 1 always connects to server A, and client 2 always connects to server C.

An anycast router can balance the load among all routes, rapidly switching from one to another. A packet from Client 1 can be routed just as easily to Server C as to Server A.[3]

Fault tolerance case

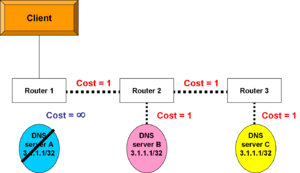

Now, simplify the scenario to have but one client (Figure 2). As long as server A is up, router 1 will see a cost of 1 to reach server A. The routing process was aware of other routes to 3.1.1.1, but there was a cost of 2 to server B and a cost of 3 to server C. Router 1 put only the lowest-cost route into its routing table.

But what if server A fails? The router knows other paths to the same address, so it will install the path that goes through router 2. The client will still receive exactly the same service from exactly the same address.[4]

Operational examples

Anycast works well for applications that do not require perfect synchronization of changes at the servers and do not need to keep track of sessions or user state. An application requiring the user to log in, for example, might get confused if the session was suddenly switched to a machine on which the user is not logged in.

One common application of anycast is the root servers for the Domain Name System. While the official list has thirteen named servers, there are actually hundreds of geographically distributed machines.

Another application is an active defense against DoS attacks. Instead of just providing more capacity to absorb the attack, or even null-routing it, it is possible to divert the attack to a set of sinkholes that analyze the traffic, and perhaps even engage with the attacker, trying to elicit traceback information, or even tarpit the attacker's machines.

When an attack is detected, the server under attack would be useless due to overload, so its address is reassigned as an anycast address of a set of sinkholes. For a single-stream attack, the sinkhole nearest the ingress router does the analysis. For a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, the entire set of sinkholes may engage.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hinden, R. & S. Deering. (February 2006), IP Version 6 Addressing Architecture., RFC 4291

- ↑ Miller, Kevin (NANOG 29 – October 2003), Deploying IP Anycast

- ↑ The figure raises a question. Do we have to assume all the routers in a load-balancing setup are anycast? Should we answer this question or change the figure?

- ↑ Isn't this how a traditional router works? Why do we need anycast for fault tolerance?