Hong Kong: Difference between revisions

imported>John Stephenson (→Democratic issues: links, tear gas, ref.) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

* Tsang, Steve. ''Government and Politics: A Documentary History of Hong Kong.'' (1995), 312pp [http://www.questia.com/read/14561367?title=Government%20and%20Politics%3a%20A%20Documentary%20History%20of%20Hong%20Kong online edition] | * Tsang, Steve. ''Government and Politics: A Documentary History of Hong Kong.'' (1995), 312pp [http://www.questia.com/read/14561367?title=Government%20and%20Politics%3a%20A%20Documentary%20History%20of%20Hong%20Kong online edition] | ||

== | ==Footnotes== | ||

{{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:00, 29 August 2024

Hong Kong (Chinese 香港; Cantonese:Heung1 Gong2; Pinyin: Xiānggǎng; literally: "fragrant harbour") is a Special Administrative Region (SAR) in the south of the People's Republic of China, and is one of the world's leading financial, industrial, and transportation centers. Hong Kong consists of a large number of islands as well as the Kowloon peninsula and territories south of the Sham Chun and Sha Tau Kok rivers on the mainland. These rivers mark the border between Hong Kong and the neighbouring sub-provincial city of Shenzhen in China's Guandong Province. China's only other Special Administration Region, Macau, lies a short distance by sea to the west of Hong Kong.

Formerly a British colony, Hong Kong has a population of 6,963,100 people[1] in an area of only 1,104 square kilometres. The territory's average population density is thus 6,420 people per square kilometre;[2] but even this figure far understates the density of most Hong Kong residential districts, as the majority of Hong's territory is sparsely inhabited.[3]. The region is low in natural resources, but has prospered due to its safe, natural, deep-water harbour. Hong Kong's ports are among the busiest in the world, and handled the equivalent of 23,998,000 standard twenty-foot containers in 2007.[4]

In 1997, British control over Hong Kong ended, and the colony returned to Chinese sovereignty. However, Hong Kong maintains its autonomy from the mainland, with separate governmental and legal systems. Hong Kong maintains its own Immigration and Customs authorities, and travel between the SAR and the mainland requires documentation, checks, and procedures similar to those required for travel to a foreign country.

Language

The main language for 95% of the population is Cantonese, one of the many varieties of Chinese. It is related to but not mutually intelligible with Mandarin. Although a dialect of Mandarin forms 'standard Chinese', Cantonese has its own standard dialect, with a written form using Chinese characters. This is quite different from written Mandarin. English is also widely spoken, due to the region's prior status as a British colony. Signs in Chinese and English are commonplace. Cantonese includes vocabulary derived from English, due to extensive contact between the two languages.

Geography

History

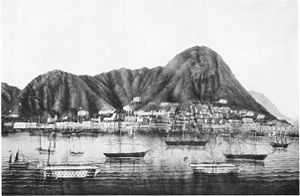

When British merchants were forced out of Canton in the 1820's, they began to use Hong Kong harbor for anchorage and storage depots. Hong Kong, with a population of 3600 villagers and 2000 fishermen, came under British control by the Convention of Chuenpi, a treaty with China in 1841, as part of the British conquest during the opium wars British foreign minister Lord Palmerston contemptuously dismissed the place as "a barren island with hardly a house upon it." Its prized harbor was used only by fishermen, pirates, and opium smugglers. However, it soon became a key and Royal Navy coaling station.

By the Treaty of the Bogue (Humen) in 1843, Chinese merchants based in the mainland were allowed free access to Hong Kong for trading purposes. By 1851 the population reached 32,000 (95% Chinese), The Second Anglo-Chinese War (1856-58) resulted in another British victory and led to the secession of the Kowloon Peninsula. Under a convention signed in Peking in 1898, the New Territories — comprising the area north of Kowloon up to the Shum Chun (Shenzhen) River and 235 islands--was leased for 99 years, primarily to forestall French or Russian occupation.

Business

In the 19th century the British colony was chiefly a naval base and as an entrepôt for trade with the mainland. An international busineess community grew up; Warren Delano, Jr., grandfather of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, worked in Hong Kong in the 1860s as a partner in the American trading firm of Russell and Company. Jardine Matheson, founded in 1832, was a British partnership that did marketing for correspondent merchants in Britain, India, and parts of south-east Asia. It became active in finance, insurance, and shipping, but its most profitable commodity was opium, which was sold, illegally, in Canton and along the coast of China. In 1843 it moved its headquarters to Hong Kong, signalling the new base for British merchants, who dominated the international trade of south China. They sent teas and silks to Europe, and imported coal, machinery, metals, wines, and liquors. In 2007 Jardine Matheson had revenues of US$ 32 billion, and is the largest employer in HKSAR after the government.[5]

Shortages of arable land, fresh water, forest and mineral resources, and skilled labor appeared to be insuperable barriers to the development of industry. However, Chinese businessmen by the 1880s were creating a distinct cultural-historical role for the colony. They contributed to China's nation-building effort by providing financing and imports China could not secure on its own. Their success made Hong Kong a valued member of the British Empire. By 1900, the colonial government appreciated the Chinese businessmen as more than profit-bound sojourners, but as allies in the struggle for order and stability, not just in Hong Kong and in south China, but in the British empire in Asia. Nationalism does not inevitably pit colonized against colonizers, for Chinese nationalism did not drive the Chinese merchants and intellectuals into opposition; the ideal of a powerful, modern China united them with the British, for both partiesrealized a strong, modern China meant a commercially vibrant China.

The Chinese nationalists played a major role in service to the Qing dynasty and the succeeding Republican governments, in leading the 1911 revolution and becoming a strategic a haven for Chinese refugees. Hong Kong's philanthropic and relief works, and the commercial and industrial activities of the entrepreneurs were role models for South China. The Chinese business community in Hong Kong, resembled the British business communities there and in Shanghai, which was larger and commercially more important before 1948. Both British and Chinese businessmen were dedicated to opening markets in China, to the point at which Hong Kong Chinese were in a sense both colonized and colonizers. Both groups benefited from their connections in the British Empire, and both were dependent on its power. Members of both societies saw themselves as permanent residents rather than as expatriates or sojourners, but they also continued to send money home to support philanthropic causes and, when necessary, to assist national war efforts. Both British and Chinese could have a number of identities: British or Chinese, imperial, national, and local. Both communities based their local identities on self-images of industriousness, entrepreneurship, and public spirit. London refused demands by British residents for self-government, arguing that saying the 98% Chinese majority would be subject to the control of a small European minority.[6]

Modernization proceeded rapidly, with the Hong Kong and China Gas Company starting in 1861, the Peak Tram in 1885, the Hongkong Electric Company in 1889, China Light and Power in 1903, the electric tramways in 1904 and the Kowloon-Canton Railway, in 1910. Successive reclamations began in 1851 — notably one completed in 1904 in Central District which produced Chater Road, Connaught Road and Des Voeux Road; and another in Wan Chai between 1921 and 1929.

A representative leader was Sir Kai Ho Kai, (1859-1914), barrister, physician, reformist, revolutionary and essayist. His grandfather was a Protestant printer in Malacca (Malasia); his father was educated at the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca and became a Protestant minister in Hong Kong as well as a rich real estate entrepreneur. Ho Kai was one of the first Chinese physicians to be professionally trained in Britain (at Aberdeen University), becoming a central figure in the history of Western medicine in China. His public service on Hong Kong's appointed Legislative Council from 1890 to 1914, his role in helping to found the Tung Wah Hospital, Alice Memorial Hospital, the Hong Kong College of Medicine and the Po Leung Kuk orphanage; he wrote numerous essays on governmental reform.[7]

Education and religion

Schooling was not compulsory but the colonial government began annual cash grants in 1847 to schools for the Chinese; there was never any effort to impose English. In 1873, the annual grants were extended to voluntary schools operated by Christian missionaries. College of Medicine for the Chinese, opened in 1887 with Sun Yat Sen as one of its first two students; it became the University of Hong Kong in 1911 and built arts, engineering and medical faculties. However, throughout the 20th century higher education opportunities were limited.

The Church Missionary Society of the Church of England promoted work in China after 1844. George Smith (1815–1871) was the first bishop of Hong Kong, 1850-64. Smith handled Anglican pastoral and missionary, and directed St. Paul's Missionary College (now St Paul's Boys' School). He spoke Chinese and conducted both Chinese and English services. Smith set up the first mission to seamen in Hong Kong and was president of the Bible Society in Hong Kong. He ordained the first two Chinese deacons in 1863. The governor appointed Smith as chairman of the education committee in 1852 and of its successor, the board of education, in 1860.[8]

Frederick Stewart (1836–1889), the first head of the government education department was a Scottish Presbyterian educator who helped structure the educational system 1862-1878. Most residents were too poor to educate their children: school attendance among the farming and large transient fishing communities was irregular and Chinese girls generally were not educated. Stewart passionately valued education for individual fulfillment and only secondly for society's needs. He established, developed, and managed both a school and a system, learning and using spoken Cantonese and written Chinese in his work. In 1873 he established a successful grant-in-aid scheme for non-government schools (generally warmly supported by missionaries) and saw a sharp increase in attendance. In 1889 he supported a successful initiative to extend government Western education taught through English to Chinese girls. His work was enthusiastically supported by the governors Sir Richard MacDonnell and Sir Arthur Kennedy, but his work was obstructed by John Pope-Hennessy, governor 1877-1882. Pope-Hennessy, a highly controversial Irish Catholic hostile to Protestants, favored the Chinese over the British, and faulted the English-language achievements of Stewart's Central School pupils and disapproved of the dual curriculum which was the school's unique and particular strength. Although language policy had been a source of controversy at various times during the 1860s and 1870s, it was not until Pope-Hennessy’s raised the issue that conflict over the roles of English and Chinese in the colony's education system came fully into the open.[9] In 1883, on the initiative of the Colonial Office, and under a new governor, Sir George Bowen, he was appointed registrar-general and protector of Chinese. In 1887 Stewart was appointed colonial secretary—the head of the permanent civil service—and he occasionally acted as governor. Through his work in setting up a government education system which accommodated the best of two cultures—English and Chinese languages, Western and Chinese curricula, and modern and traditional pedagogies—Stewart made a lasting impact which accelerated the modernization of China. His own educational example, the pedagogical materials he produced, and his graduates all were important. Bilingual and bicultural pupils from the flagship Hong Kong Government Central School for Boys staffed many Hong Kong and imperial institutions; many attended the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, of which Stewart was the first rector. Several won positions of influence in the imperial Chinese or Hong Kong colonial governments; others, admiring Western ideals, became revolutionaries, most notably Sun Yat Sen, the first president of China.[10]

Great Depression

In 1932, facing a worldwide Great Depression and higher tariffs from the United States, the British Commonwealth nations decided at the Imperial Economic Conference to protect industry and agriculture in the Empire by raising tariffs on imports from outside the Empire and encouraging colonial entrepreneurs. Since Hong Kong was a free port with no customs duties on imports or exports, industrialization there was different than in other British colonies, where industry could only be established with the aid of protective tariffs and other government assistance, and where manufactured goods could only be sold in local markets. Hong Kong's industrialization rapidly expanded thanks to the new preference for goods made inside the Empire, and especially to the higher tariffs on Japanese textiles, footwear, and other goods. Chinese entrepreneurs in Hong Kong soon took over from the Japanese as the main competitors of British manufacturers in textiles and rubber footwear. The local and regional market expanded, with 24,000 ocean-going ships clearing the harbor in 1939. The large-scale relocation of industrial enterprises from mainland China began in the late 1930s, and resumed after the war.[11]

Second World War

London realized it could never defend the isolated colony against Japan, but had to send forces to maintain imperial prestige. Indian and Canadian troops were sent in 1941 but they lacked training, equipment, and ammunition. They served a sacrificial role, with 6500 imprisoned for the duration, while British Commonwealth forces sought a major victory in North Africa. Refugees pured in from the mainland pushing the population well over one million, with extremely crowded conditions. Japan ruled from December, 1941 to September 1945, a time of hyperinflation and food shortages. Upwards of half the population left for the mainland.[12]

Social trends

Open currency markets and a free trade policy in Hong Kong after World War II gave it great economic advantages over Shanghai, whose government-controlled import-export trade could not compete with the British colony. In the late 1940s thousands of businessmen and professionals from Shanghai and other cities fled to Hong Kong top escape the imminent takeover of China by the Communists.

Despite a low birth rate, Hong Kong's population grew rapidly after 1945, as it became a base for entrepreneurs and a haven for refugees from poverty, war and Communism in China. The population tripled from 600,000 in 1945 to 1.8 million in 1948, then grew to 4 million in 1970 and 5.6 million in 1997. Steady growth continues, reaching 6.9 million in 2006.

The colony's strong high school system produced some of the professionals and skilled workers who contributed to rapid economic development after 1945, but they were outnumbered by new arrivals from China. Hong Kong's open and competitive employment system offered an important channel for upward social mobility, which tended to forestall a growth in class consciousness. Graduates joined an English-speaking elite and took pride in its acquaintance with the British culture. This elite was then incorporated by the British Establishment. This integration reduced potential friction between the colonial government and the local elite, who displayed far less antagonism or demands for independence than elites in other colonies. Demands for political participation emerged in the 1970s, as the colonial government vastly expanded its social service commitments. Its policy of "administrative absorption" encompassed more elites from all social strata. Its image was also improved by attempts to be a "government by consultation," while the threat of a takeover by Communist China undercut demands for autonomy. Economic development consistently raised the people's living standards and lowered their demand for political participation. Hong Kong elites were proud of not being affected by the "British disease," the symptoms of which included too much social welfare, militant trade unionism, frequent labour disputes, and a decline in economic competitiveness, as affected Britain itself in the 1970s. Radical ideologies were unattractive to the community and the Maoist factions gained little support. After 1984 both Britain and China promised more democracy, but as of 2008 there still is little of it.[13]

Economic boom

In the 1950s, Hong Kong viewed Guangdong on the mainland as its economic past: an underdeveloped hinterland of cottage industries and peasant agriculture. Guangdong, meanwhile, looked on Hong Kong as its political past: a territory oppressed by colonialism. That is, Hong Kong leaders saw Guangdong as socialist=planned=unfree=poor. Meanwhile the Commuist leaders in Guangdong saw Hong Kong as colonial=exploitative=class stratified=dehumanizing.[14]

The colony experienced some of the highest economic growth rates in world history during the last half of the 20th century. In the 1960s its average annual rate of growth was 13.2%, setting a world record. New factories opened, especially textiles and plastics. A major construction boom continued almost non-stop. In the 1960s the port became as a major center for world trade, exceeding all of China by 30%. It became a major international financial center. Low taxation, a strong currency, and a free currency exchange attracted international banks and foreign investment, although uncertainty regarding the 1997 takeover sent some investors to Canada. In the 1970s the growth rate slowed to a very high 8% annually. Per capita income soared, despite the fast growing population, and was the third highest in Asia by 1980, albeit less than half that of Japan.

In 1971 the colonial government made education compulsory and virtually free. Total school enrollment in 1981 was 1,339,000, but included a mere 16,000 full-time higher education students. In 1989 Governor Edward Youde moved to expand and strengthen higher education in response to public demands. He envision the founding of a world class university, an Asian equivalent of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1991 the colony established the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST). More expansion took place in the 1990s, resulting in nine major centers of higher education, with enrollment expanded by 50%.[15]By 2006 the most prestigious school, the University of Hong Kong, had 11,600 undergraduates, 7,900 postgraduates, and 2,000 MPhil and PhD students.

1997

When Britain turned Hong Kong over to China in 1997 it was the most modern colonial metropolis in the world, where robust entrepreneurship flourished under a British legal system providing a high degree of civil liberties for its citizens, but which had never set up a democratic system. Between 1960 and 1982, Hong Kong showed the staggering average growth rate of 7.0% per year, then held at 6.7% annually to 1992. In 1995, Hong Kong's GDP per person (in parity purchasing power) was the third highest in the world.

In 1997, at the end of the 99 year lease, the whole of the Hong Kong territory was returned to China. A "one country, two systems" model for 50 years was promised by China's leader Deng Xiaoping, and the formula was accepted by Britain. Beijing selected the Basic Law Drafting Committee in 1985, making it clear it placed top priority on the stability and prosperity of the territory and that radical political reforms would be unlikely. Of the 59 members there were 23 members from Hong Kong, most of them prominent businessmen and leading professionals. The interests of the Establishment in Hong Kong apparently were assured, as the Chinese authorities were keen to retain Hong Kong's attractiveness to investors. The Basic Law Drafting Committee favoured an "executive-led" system of government for the future HKSAR with power concentrated in the hands of the Chief Executive, rather than the weak Legislative Council.

The 1985 elections to the colonial Legislative Council involved representation of different interest groups; there were a mere 70,000 eligible voters, of whom only 25,000 voted.The September 1985 elections to the Legislative Council were based on the electoral college, comprising members of the District Boards, the Urban Council and the Provisional Regional Council, and the functional constituencies.[ 10] Qualified voters therefore only numbered about 70,000 and those who actually voted amounted to about 25,000.

To rule after 1997 China created its first Special Administration Region, and as a result, Hong Kong became largely autonomous with its own government and laws, distinct from that of the rest of the People's Republic. All final decisions, however, were made by the government of China, but the influence was light-handed and "soft" before 2003.[16]

Democratic issues

On 1 July 2003, over half a million Hong Kong citizens staged a mass protest against the poor governance of the post-handover SAR government. The grievances of the marchers quickly snowballed into a widely backed movement for democracy, and another large rally was held on 1 July 2004. The landslide support for pro-democratic candidates during the local elections held on 23 November 2003 unnerved Beijing over its possible loss of control over Hong Kong. The government of China quickly shifted from a soft-line approach that talked about virtual autonomy to a hard-line approach, attempting to dampen the local democracy movement. Beijing banned universal suffrage for the elections of a Chief Executive in 2007 and a legislature in 2008. There were five fundamental causes of Hong Kong's broad-based demand for full democracy. First economic uncertainly rose sharply after 1999, as the competitiveness of the Hong Kong economy slipped and the transition to a knowledge economy was hindered by stagnant rates of university attendance. Secondly, the level of economic inequality increased,[17] along with a sense that cronyism was rampant and getting worse. Thirdly the government deficit has soared, leading to cutbacks in government services; by 2003 the government had spent half the financial reserves left by the British, and sold land assets to cover the deficit. At a deeper level citizens are anxious about their lack of voice in an authoritarian polity.[18] The The fifth fundamental problem was the failure of the new "Principal Officials Accountability System" and the growth of popular distrust towards the non-democratic system. [19]

In August 2014, the Chinese government announced its intention to allow only approved candidates to contest the 2017 election of Hong Kong's chief executive. On 22nd September, student groups announced a week-long boycott of classes in protest. By 28th September, tens of thousands of people, many part of the 'Occupy Central' movment, had blocked roads and brought the business district to a standstill, and police at times deployed tear gas to disperse crowds. The demonstrations were dubbed the 'Umbrella Revolution' due to the umbrellas participants used to protect themselves from the gas, police pepper sprays and the heat.[20]

Further reading

- Carroll, John M. A Concise History of Hong Kong (2007) 270 pages excerpt and text search

- DK. Eyewitness Top 10 Travel Guides: Hong Kong (2002) excerpt and text search

- Reiber, Beth. Frommer's Hong Kong (2007) excerpt and text search

- Stone, Andrew. Lonely Planet Hong Kong & Macau City Guide (2008) excerpt and text search

- Tsang, Steve. A Modern History of Hong Kong (2007) excerpt and text search

- Vickers, Claire. Hong Kong - Culture Smart!: a quick guide to customs and etiquette (2006) excerpt and text search

- Welsh, Frank. A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong (1993), 624pp readable and well-researched history

- Wright, Rachel. Living and Working in Hong Kong: The Complete Practical Guide to Expatriate Life in China's Gateway (2008) excerpt and text search

Primary sources

- Endacott, G. B., ed. An Eastern Entrepot: A Collection of Documents Illustrating the History of Hong Kong (1964) 293 pp

- Tsang, Steve. Government and Politics: A Documentary History of Hong Kong. (1995), 312pp online edition

Footnotes

- ↑ http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hong_kong_statistics/statistics_by_subject/index.jsp

- ↑ Note: According to the March/April 2009 issue of BBC Knowledge Magazine, "The city [of Hong Kong] has an average of 6200 people per square kilometer [16062 people per square mile], the second highest population density in the world after Monaco. Globally, the average is 48 people per square kilometer [124 people per square mile]." By square kilometer or square mile, the density of Hong Kong is approximately 129 times the global average.

- ↑ http://www.info.gov.hk/info/hkbrief/eng/fact.htm

- ↑ http://www.pdc.gov.hk/docs/Hkport.pdf

- ↑ See Jardine's History

- ↑ John Carroll, "Colonialism, Nationalism, and Difference: Reassessing the Role of Hong Kong in Modern Chinese History." Chinese Historical Review 2006 13(1): 92-104. Issn: 1547-402x

- ↑ G. H. Choa, The Life and Times of Sir Kai Ho Kai: A Prominent Figure in Nineteenth-Century Hong Kong. (2nd ed. 2000)

- ↑ Gillian Bickley, "Smith, George (1815–1871)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Sept 2004); online edn, Jan 2008

- ↑ Kate Lowe and Eugene McLaughlin. "Sir John Pope Hennessy and the 'native race craze': colonial government in Hong Kong, 1877–1882", Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 20 (1992), 223–47 ·

- ↑ Gillian Bickley, "Stewart, Frederick (1836–1889)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008

- ↑ Norman Miners, "Industrial Development in the Colonial Empire and the Imperial Economic Conference at Ottawa 1932." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 2002 30(2): 53-76. Issn: 0308-6534

- ↑ Andrew J. Whitfield, Hong Kong, Empire and the Anglo-American Alliance at War, 1941-1945. (2001) online edition

- ↑ Joseph Y.S. Cheng, "Elections and Political Parties in Hong Kong's Political Development", Journal of Contemporary Asia, 2001, 31#3 346-374

- ↑ Seth Harter, "'Time Is Moving Forward, but We Are Moving Faster': Racing towards Modernity in Hong Kong and Guangdong, 1945-1962." (2006).

- ↑ Timothy Man-kong Wong, "From Expansion to Repositioning: Recent Changes in Higher Education in Hong Kong," China: An International Journal 2#1 March 2004, pp. 150-166 in Project Muse

- ↑ Willy Lam, "Beijing's hand in Hong Kong politics," Association for Asian Research June 14, 2004, online

- ↑ Li Zhang, "Economic Growth and Income Inequality in Hong Kong: Trends and Explanations," China: An International Journal 3#1 March 2005, pp. 74-103 in Project Muse

- ↑ Yushuo Zheng, "Hong Kong's Democrats Stumble," Journal of Democracy 16#1 January 2005, pp. 138-152 in Project Muse

- ↑ Ming Sing, "The Legitimacy Problem and Democratic Reform in Hong Kong." Journal of Contemporary China 2006 15(48): 517-532. Issn: 1067-0564 Fulltext: Ebsco; Christine Loh, and Richard Cullen, "Political Reform in Hong Kong: the Principal Officials Accountability System. The First Year (2002-2003)." Journal of Contemporary China 2005 14(42): 153-176. Issn: 1067-0564 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ BBC News: 'How the humble umbrella became a HK protest symbol'. 29th September 2014.