Greenhouse effect: Difference between revisions

imported>Paul D Farrar |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

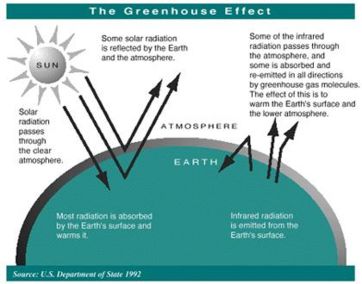

The ''' | [[Image:Gef.jpg|EPA illustration of greenhouse effect.<br/> <small> The sun radiates energy to the earth mainly in the form of ultraviolet and visible (short wavelength) light. This energy, which is not absorbed by a clear atmosphere, warms the surface of the earth. The warm surface radiates energy back into space in the form of infrared (long wavelength) light. Much of the infrared energy radiated by the surface does not disappear in space, but is absorbed by greenhouse gases present in the lower atmosphere. This absorption warms the lower atmosphere.</small> | ||

|right|thumb|362px]] | |||

:''See also: [[Global warming]]'' | |||

The '''greenhouse effect''' (or "atmospheric effect") is a general attribute of planets and moons with atmospheres. It is the difference between surface radiation and top-of-atmosphere radiation due to the presence of [[greenhouse gas|greenhouse gases]]. For example, in the case of the [[Earth]], the surface emits 390 W/m<sup>2</sup><ref>Watts per square metre</ref> (averaged over a year and the whole surface), but the emission at the top of the atmosphere is 235 W/m<sup>2</sup>, giving a global-average greenhouse effect of 155 W/m<sup>2</sup><ref name="Tren96">Trenberth, K, <i>et al</i>., 1996. in <i>Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change</i>, Cambridge Univ. Press.</ref>. The top-of-atmosphere outgoing radiation balances the absorbed 235 W/m<sup>2</sup> of solar radiation (342 W/m<sup>2</sup> incident minus 107 W/m<sup>2</sup> reflected). The term "greenhouse effect" is a misnomer, since actual [[greenhouse]]s operate by a different mechanism. | |||

== | The greenhouse effect was discovered by [[Joseph Fourier]] in 1824 and first investigated quantitatively by [[Svante Arrhenius]] in 1896 <ref name="urlWater Vapor Feedback And Global Warming1 - Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 25(1):441 - Abstract">{{cite web |url=http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.energy.25.1.441?cookieSet=1&journalCode=energy.2 |title=Water Vapor Feedback And Global Warming1 - Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 25(1):441 - Abstract |format= |work= |accessdate=7.02.08}}</ref><ref name="urlHistorical Overview | ||

of Climate Change Science">{{cite web|url=http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_Ch01.pdf |title=Historical Overview | |||

of Climate Change Science |format= |work= |accessdate=7.02.08}}</ref>. | |||

== The | == The physics of the greenhouse == | ||

The essential condition for a greenhouse effect is the presence in a planetary atmosphere of gases that absorb (and emit) in the [[thermal radiation]] band of the planetary surface | The essential condition for a greenhouse effect is the presence in a planetary atmosphere of gases that absorb (and emit) in the [[thermal radiation]] band of the planetary surface or lower atmosphere. Greenhouse gases often are transparent, or nearly so, to incoming solar radiation (ozone and water vapor are exceptions). The surface thermal radiation band is in the long-wave [[infrared radiation| infrared]] region (3.5 µm - 100 µm). The greenhouse gases are triatomic (or more, but note the exception for [[Titan]]) molecules which absorb energy into a variety of [[molecular sprectra|rotational, bending, and stretching modes]]. Common solar-system gases that meet the requirements are [[water]] vapor (H<sub>2</sub>O), [[carbon dioxide]] (CO<sub>2</sub>), [[ozone]] (O<sub>3</sub>), and [[methane]] (CH<sub>4</sub>). For Earth, H<sub>2</sub>O, CO<sub>2</sub>, and O<sub>3</sub> provide most of the greenhouse. Common homonuclear diatomic gases, such as [[nitrogen]] (N<sub>2</sub>) and [[oxygen]] (O<sub>2</sub>), do not afford dipole transitions in the infrared and hence hardly absorb energy. | ||

The greenhouse effect occurs at a state near local thermodynamic equilibrium. When a gas molecule is excited by an infrared quantum, the energy is | The greenhouse effect occurs at a state near local thermodynamic equilibrium. When a gas molecule is excited by an infrared quantum, the energy is quickly redistributed according to the principles of [[statistical mechanics]]. Thus infrared absorption adds energy and heats the gas. Likewise, thermal infrared emission withdraws energy and cools the gas. In simple terms, this means that an atmosphere that contains greenhouse gases absorbs heat by absorbing radiation of the proper wavelength as it passes through, and loses heat by emitting the same wavelength. (By Kirchoff's law, absorptivity equals emissivity for any given wavelength.) Whether the temperature rises or falls depends on the balance between the two effects and on any other heating or cooling processes. On Earth, transfer of sensible heat from the ground and the release of [[latent heat of vaporization]] when water vapor condenses also are significant sources of energy to the atmosphere. | ||

It should be noted that the greenhouse gas molecules maintain their identity and are not destroyed or chemically altered. This differs from the case of ionizing radiation absorption (such as the absorption of solar [[ultraviolet radiation]] by [[oxygen]] and [[ozone]]). | |||

== | == References and notes == | ||

<references/>[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 23 August 2024

The sun radiates energy to the earth mainly in the form of ultraviolet and visible (short wavelength) light. This energy, which is not absorbed by a clear atmosphere, warms the surface of the earth. The warm surface radiates energy back into space in the form of infrared (long wavelength) light. Much of the infrared energy radiated by the surface does not disappear in space, but is absorbed by greenhouse gases present in the lower atmosphere. This absorption warms the lower atmosphere.

- See also: Global warming

The greenhouse effect (or "atmospheric effect") is a general attribute of planets and moons with atmospheres. It is the difference between surface radiation and top-of-atmosphere radiation due to the presence of greenhouse gases. For example, in the case of the Earth, the surface emits 390 W/m2[1] (averaged over a year and the whole surface), but the emission at the top of the atmosphere is 235 W/m2, giving a global-average greenhouse effect of 155 W/m2[2]. The top-of-atmosphere outgoing radiation balances the absorbed 235 W/m2 of solar radiation (342 W/m2 incident minus 107 W/m2 reflected). The term "greenhouse effect" is a misnomer, since actual greenhouses operate by a different mechanism.

The greenhouse effect was discovered by Joseph Fourier in 1824 and first investigated quantitatively by Svante Arrhenius in 1896 [3][4].

The physics of the greenhouse

The essential condition for a greenhouse effect is the presence in a planetary atmosphere of gases that absorb (and emit) in the thermal radiation band of the planetary surface or lower atmosphere. Greenhouse gases often are transparent, or nearly so, to incoming solar radiation (ozone and water vapor are exceptions). The surface thermal radiation band is in the long-wave infrared region (3.5 µm - 100 µm). The greenhouse gases are triatomic (or more, but note the exception for Titan) molecules which absorb energy into a variety of rotational, bending, and stretching modes. Common solar-system gases that meet the requirements are water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), ozone (O3), and methane (CH4). For Earth, H2O, CO2, and O3 provide most of the greenhouse. Common homonuclear diatomic gases, such as nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2), do not afford dipole transitions in the infrared and hence hardly absorb energy.

The greenhouse effect occurs at a state near local thermodynamic equilibrium. When a gas molecule is excited by an infrared quantum, the energy is quickly redistributed according to the principles of statistical mechanics. Thus infrared absorption adds energy and heats the gas. Likewise, thermal infrared emission withdraws energy and cools the gas. In simple terms, this means that an atmosphere that contains greenhouse gases absorbs heat by absorbing radiation of the proper wavelength as it passes through, and loses heat by emitting the same wavelength. (By Kirchoff's law, absorptivity equals emissivity for any given wavelength.) Whether the temperature rises or falls depends on the balance between the two effects and on any other heating or cooling processes. On Earth, transfer of sensible heat from the ground and the release of latent heat of vaporization when water vapor condenses also are significant sources of energy to the atmosphere.

It should be noted that the greenhouse gas molecules maintain their identity and are not destroyed or chemically altered. This differs from the case of ionizing radiation absorption (such as the absorption of solar ultraviolet radiation by oxygen and ozone).

References and notes

- ↑ Watts per square metre

- ↑ Trenberth, K, et al., 1996. in Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change, Cambridge Univ. Press.

- ↑ Water Vapor Feedback And Global Warming1 - Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 25(1):441 - Abstract. Retrieved on 7.02.08.

- ↑ [http://ipcc-wg1.ucar.edu/wg1/Report/AR4WG1_Print_Ch01.pdf Historical Overview of Climate Change Science]. Retrieved on 7.02.08.