Venn diagram: Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews (→References: fix labeling to be X&Y instead of A&B) |

imported>John R. Brews m (reorder words) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

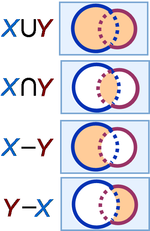

{{Image|Venn diagrams XY.PNG|right|150px|Venn diagrams; set ''X'' is the interior of the blue circle (left), set ''Y'' is the interior of the red circle (right). The rectangle represents the universal set. The sets designated by symbols on the left are colored orange.}} | {{Image|Venn diagrams XY.PNG|right|150px|Venn diagrams; set ''X'' is the interior of the blue circle (left), set ''Y'' is the interior of the red circle (right). The rectangle represents the universal set. The sets designated by symbols on the left are colored orange.}} | ||

A '''Venn diagram''' is | A '''Venn diagram''' is a visualization of logical concepts and propositions using arrangements of intersecting circles. | ||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

*************** | *************** | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

**************** | **************** | ||

--> | --> | ||

==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

Suppose X and Y are [[Set (mathematics)|sets]], for example, collections of some description. Various operations allow us to build new sets from them, and these definitions are illustrated using the three Venn diagrams in the figure.<ref name=Oakhill/> If we assume the rims contain ''no'' points, the figure is straightforward. However, some minutiae arise if the rims are considered to be additional sets with points of their own. These details are described in a footnote.<ref name=details/> | Suppose X and Y are [[Set (mathematics)|sets]], for example, collections of some description. Various operations allow us to build new sets from them, and these definitions are illustrated using the three Venn diagrams in the figure.<ref name=Oakhill/> If we assume the rims contain ''no'' points, the figure is straightforward. However, some minutiae arise if the rims are considered to be additional sets with points of their own. These details are described in a footnote.<ref name=details/> | ||

Revision as of 13:31, 11 July 2011

A Venn diagram is a visualization of logical concepts and propositions using arrangements of intersecting circles.

Examples

Suppose X and Y are sets, for example, collections of some description. Various operations allow us to build new sets from them, and these definitions are illustrated using the three Venn diagrams in the figure.[1] If we assume the rims contain no points, the figure is straightforward. However, some minutiae arise if the rims are considered to be additional sets with points of their own. These details are described in a footnote.[2]

Union

The union of X and Y, written X∪Y, contains all the elements in X and all those in Y.

Intersection

The intersection of X and Y, written X∩Y, contains all the elements that are common to both X and Y.

Set difference

The difference X minus Y, written X−Y or X\Y, contains all those elements in X that are not also in Y.

Complement and universal set

The universal set (if it exists), usually denoted U, is a set of which everything under discussion is a member. In pure set theory, normally sets are the only objects considered. In that case, U would be the set of all sets. However, one may also consider sets that are collections of numbers, or colors, or books, for example; see Set (mathematics).

In the presence of a universal set we can define X′, the complement of X, to be U−X. Set X′ contains everything in the universe apart from the elements of X.

History

The use of Venn diagrams was introduced by John Venn (1834-1923).[3] A brief biography is found in Hurley.[4]

References

- ↑ Alan Garnham, Jane Oakhill (1994). “§6.2.3b: Venn diagrams”, Thinking and reasoning. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 105 ff. ISBN 0631170030.

- ↑ If we suppose the perimeters of the circles to contain no points, no complication occurs. If, on the other hand, we consider them to have non-zero width, the figure contains four sets (besides the universal set), set X (white) of points interior to the blue circle, set Y (also white) of points interior to the red circle, set RimX (blue) and set RimY (red). These sets are not disjoint when the two circles overlap, for example, as they do in the figure. In cases of overlap such as the depicted union X∪Y, the red rim enters the interior of the blue circle. Hence, those points in set RimY that are also inside the blue circle are also in set X. They have dual identity, and can be taken either as red or as white points. The figure shows points in the designated union X∪Y as orange. It includes all points in X or in Y or in both, and thus includes the ambiguous, dual-identity points of set RimY. Accordingly, these dual-identity points are part of the union X∪Y and, to make this point, the spaces in the dashed part of the perimeter are colored orange, as are all the points in the union. Likewise for the dual-identity points of set RimX that are part of X∪Y. In set X−Y of the third panel, as a different example, the spaces in the dashed perimeters are colored to show their dual identities as well: the dashed perimeter portion of blue set RimX is also part of set Y as shown by white spaces. Likewise, the dashed part of red set RimY also is part of set X, and hence also part of set X−Y as shown by the orange-colored spaces.

- ↑ John Venn (1883). "On the employment of geometrical diagrams for the sensible representation of logical propositions". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society: Mathematical and physical sciences 4: pp. 47 ff. and also John Venn (1881). “Chapter V: Diagrammatic representation”, Symbolic logic. Macmillan, pp. 100 ff. Symbolic Logic available also from Chelsea Pub. Co. ISBN 0828402515 (1979) and from the American Mathematical Society ISBN 0821841998 (2006).

- ↑ Patrick J. Hurley (2007). “Eminent logicians: John Venn”, A concise introduction to logic, 10th ed. Cengage learning, p. 252. ISBN 0495503835.

Note: CZ:List-defined references methodology is used for references here.