Texas, history

The American state of Texas has a history stretching back centuries. Texas history has embodied the republican political ideals and values shared by all Americans, that is, a devotion to personal liberty, rampant individualism, economic opportunity, and democratic politics. A strong leavening of Hispanic culture makes the southern half of Texas distinct.

Spanish Texas

Exploration

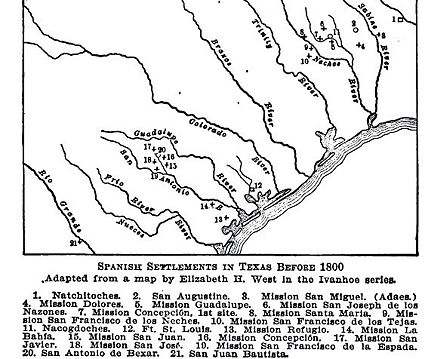

Spanish interest in Texas dates from the mapping of the Gulf of Mexico by Alonso Alvárez de Pineda in 1519. Juan Ponce de León's expedition to Florida in 1513 and the completion of the conquest of the Aztecs quickened Spanish concern with the lands to the north. In 1528-36 Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and in 1540-44 Francisco Vásquez de Coronado explored much of western Texas, fruitlessly seeking the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. De Vaca and Coronado's reports, stressing Indian hostility and the arid nature of the land, discouraged permanent settlement north of the Rio Grande.

The Spanish title to Texas remained uncontested until 1684, when French soldiers and colonists erected Fort Saint Louis in the vicinity of Matagorda Bay. They were forced out by local Indians. Alarmed by the French intrusion, Alonso de León led an expedition northward from the Rio Grande and established three missions in east Texas. Continuing border struggles with French forces across the Sabine River led to the creation of additional missions and presidios (forts).

Spain founded San Antonio in 1718 as its principal military garrison. Emanating from San Antonio, campaigns, generally unsuccessful, were mounted against the Apache, Comanche, and Tonkawa of central Texas, although the barrier to significant permanent colonization was not lifted. In 1762 France ceded western Louisiana to Spain. Relieved of the French threat on its borders, Spanish authorities abandoned the missions and presidios between the Trinity and Red rivers and relocated the several hundred colonists at San Antonio. A rancher, Gil Ybarbo, acted as spokesman for a number of settlers who preferred to remain in the area. Sent by force to San Antonio in 1790, they returned of their own will and founded the city of Nacogdoches, which became the major Spanish city in east Texas.

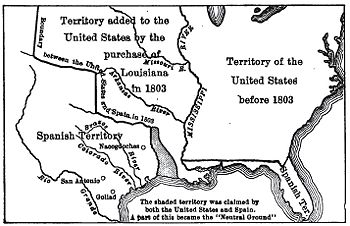

In 1800, Spain returned western Louisiana to France. In the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 the entire Louisiana territory was sold by France to the U.S. Boundary disputes between the U.S. and Spain soon followed along the Texas border, and in 1806 both nations signed the "Neutral Ground Agreement." Entered into by American and Spanish military commanders, the compact stated that neither country would exercise sovereignty over the land between the Sabine River and the Arroyo Hondo, just west of Natchitoches, in what is now Louisiana. Finally, in 1819 the Adams-Onís Treaty, ratified in 1821, fixed the northern boundary of Spanish Texas at the Sabine River.

American settlers

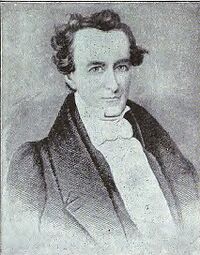

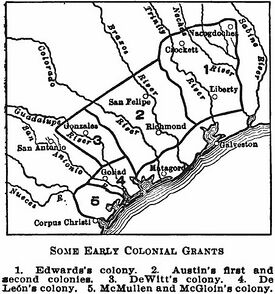

American colonization of Texas began in 1821 under the leadership of Moses Austin, who was awarded a permit by Spanish authorities at San Antonio to settle 300 families in Texas. The contract was later honored by the National Congress of Mexico after independence was won. Austin died on his return to the United States to begin the task of colonization, but the provisions of the agreement were subsequently carried out by his son Stephen Austin. Empresarios were licensed by the Mexican government and continued the recruiting of colonists for permanent settlement in Texas. Attracted by the prospect of free land--the United States had no such policy at the time--the bulk of settlers came from the states of the Old South, as well as from Britain, Ireland, and Germany. Later efforts to balance the American predominance by encouraging Mexicans to colonize proved generally unsuccessful.

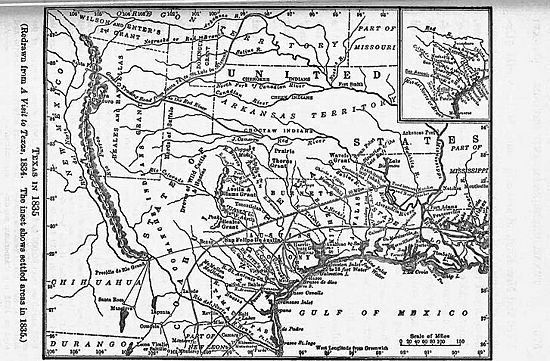

In 1835, on the eve of the revolution, there were approximately 25,000 colonists residing in Texas, plus several thousand Mexicans, called "Tejanos," as well as Indian tribes that were not under control of Mexico. Slavery of blacks was a major question. After lengthy bargaining with the Mexicans, Stephen Austin had assured his colonists that slavery had obtained legal recognition, but with the stipulation that children born to slaves in Texas would be emancipated at the age of fourteen. But the institution was placed in jeopardy again in 1827, when the state legislature of Texas-Coahuila, comprised entirely of Mexicans, sought to prohibit slavery. Relief was obtained from this decree and from an executive proclamation of emancipation in 1829. The law of April 6, 1830, once again outlawed slavery in the province but recognized a subterfuge known as "work contracts" to evade the terms of the law.

Revolution

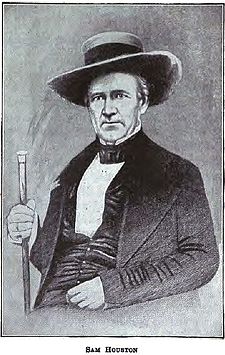

Although full legal slavery was not allowed, slavery in practice existed because of the lifetime labor contracts. The fight for independence was not waged to protect property in slaves. The colonists' specific grievances were lack of trial by jury, the use of Spanish as the official language in legal and commercial transactions, and burdensome customs regulations. The basic cause of the Texas Revolution lay in the conflicting political and social ideologies of the Mexican government and the American pioneers. Some of the colonists believed that outstanding differences could be resolved if Texas were granted separate statehood, but a more radical faction, led by Sam Houston, looked to complete autonomy and eventual annexation by the United States. Ethnic tension between Anglos and Hispanics was a minor factor, since the 30,000 or so Anglos of East Texas had only limited contact with Mexicans; furthermore, most 4,000 or so Tejanos fought alongside Anglos in the conflict with Mexico City.

When Antonio López de Santa Anna seized dictatorial authority in Mexico City in 1834 and called for additional troops to invade Texas, a military conflict became inevitable. The first clash of the war for independence took place at Gonzales on October 2, 1835. Encouraged by the relative ease of their triumph in that skirmish, the Texan "Army of the People" moved quickly to capture Goliad; in December, San Antonio was occupied after the Mexican garrison capitulated. Houston negotiated a treaty whereby the Indians in the region, with about 3,000 warriors, remained neutral.

Texas was momentarily free of Mexican troops, but in the interim an invasion force was organizing. In late February 1836 the main contingent of Santa Anna's army reached San Antonio, where the Texas defenders were encamped in the Alamo, a church fortress dating from the Spanish missionary period. Although vastly outnumbered, the garrison of some 180 defenders held out until the last man. William B. Travis, David Crockett, and James Bowie were among those who died here. "Remember the Alamo!" became not only a battle cry at the time, but an iconic memory stereotyping brutal, blood-thirsty Mexicans slaughtering valiant, freedom-loving Anglo-Texans.

Campaigning along the coast, Gen. José Urrea forced the surrender of Col. James Fannin at Goliad. Even though Urrea had pledged honorable treatment, Santa Anna personally ordered the deaths of Fannin and about 400 of his followers; and on Palm Sunday the executions were carried out by a firing squad. Since the majority of Fannin's men had recently arrived in Texas as volunteers from the United States, the executions were designed to discourage further aid in the cause of Texas.

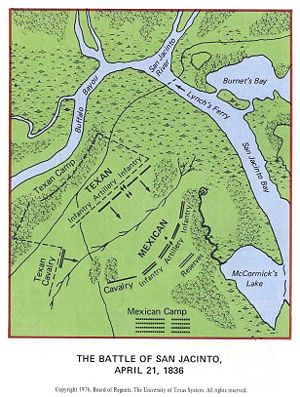

News of the fall of the Alamo reached Gen. Houston at Gonzales. Mustering a band of early colonists to Texas and some American volunteers, Houston retreated to the Brazos River, casually pursued by an overconfident Santa Anna. Believing victory to be in his grasp, the Mexican commander turned to pursue the Texas provisional government at Harrisburg; but, spurred by President David G. Burnet, the administrators escaped to Galveston. Now convinced that the strategic position was in his favor, Houston left his encampment along the Brazos and blocked Santa Anna's troops at San Jacinto as they tried to regain their original position. The decisive battle of the campaign was fought at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. Inspired by the rallying shout, "Remember the Alamo, remember Goliad," the Texans vanquished the Mexican army and imprisoned its leader. In return for his life Santa Anna signed the Treaties of Velasco that recognized the independence of Texas, with its boundary at the Rio Grande.[1]

The Texas navy also contributed to the victory. Failure to control the sea lanes of the Gulf of Mexico impeded the movement of supplies to Mexican troops and compelled Santa Anna to undertake a lengthy and hazardous overland march into Texas. Financed mainly by contributions from the United States, four Texas sloops proved more than a match for Santa Anna's naval squadrons. But in the period of the early republic the navy languished under Houston as Mexico partially blockaded the Texas coast. President Mirabeau B. Lamar determined to change the situation and embarked on a policy of naval construction. A partial alliance was entered into with the state of Yucatán, which was also seeking independence from Mexico. The navy was employed in that campaign.[2]

Republic

During the early stages of the war, Texas had been governed by a "Consultation." When all hope of a negotiated settlement proved unrealistic and Mexican liberals failed to support the goal of separate statehood, a convention was called to debate the question of independence. A declaration of independence was essential to facilitate volunteering and financial aid from the United States, and on Mar. 2, 1836, it was promulgated. A constitution for an independent Texas was also written, with the stipulation that it would not become legally binding until ratified by the people. With independence achieved, the Republic of Texas was born. Elected president in September 1836, Houston quickly turned his attention to the internal problems of land legislation, defense against Mexico and Indian raids, and a sound financial base for Texas. But Mexico soon repudiated the Treaty of Velasco, whereby Santa Anna had acknowledged Texan independence. The United States became the first nation to commence diplomatic relations with Texas, and Britain soon followed. Annexation talks were tentatively begun but were quickly abandoned in the face of substantial northern antislavery pressure. Lamar was elected president in 1838. Believing that the likelihood of annexation was small, Lamar opened diplomatic relations with Britain and France; they tried and failed to have Mexico face reality and recognize the new republic, which originated in a revolution just as Mexico itself had in 1821. When Mexico refused to meet with peace commissioners, Lamar launched a military expedition to Santa Fe in order to assert the Texan claim to the Rio Grande as its western boundary. Miscalculating the anti--Santa Anna sentiment in New Mexico, the poorly led Texans were captured and marched in irons overland to Mexico City; they were eventually released.

Annexation was highly controversial in the U.S., primarily because anti-slavery forces did not want to see new territory opened for the expansion of slavery, and Whigs opposed any geographical expansion (because it would delay modernization).[3] Nevertheless Texas grew rapidly, reaching 100,000 population by 1846, with settlements reaching as far to the northwest as Waco and Fort Worth. The capital was moved to Austin, in the west.

Texans waged intermittent warfare against the Indians, particularly the Cherokee and Comanche, who continuously raided frontier settlements. President Houston had a tolerant policy, but President Lamar did not. When the Cherokee were negotiating for Mexican support to attack frontier settlements, Lamar decided to buy them out. They would not sell and Texas drove them out in 1839; they resettled in what is now Oklahoma. The Comanches and Texans fought a series of pitched battles until Houston became president again in 1841 and made peace again.[4] At the same time, the new republic initiated a progressive public school and homestead program. Houston was reelected in 1841. Despite numerous border provocations, he insisted on a posture of peace toward Mexico. Financial conditions made stability imperative as the republic's indebtedness approached $10 million and the value of Texas currency depreciated to less than twenty cents on the dollar. Rivalry between east and west Texas over land titles and the location of the permanent seat of government also troubled the president.

Annexation 1845

The capstone of his Republic was the successful conclusion of the annexation negotiations with the U.S. Fear of British designs and the increasing economic importance of Texas spurred President John Tyler to reopen talks. A treaty of annexation was rejected by the U.S. Senate, mainly by anti-slavery votes, and the question of annexation became the major issue in the election of 1844. Democrat James K. Polk's victory for president on a platform calling for the "reannexation" of Texas prompted the passage of a joint congressional resolution. A final Mexican offer of independence, backed by England and France, was overwhelmingly spurned by the people of Texas. All formalities were completed when the Texas constitution was accepted by Congress, and the state officially joined the Union on Dec. 29, 1845. Since Houston had left office in 1844, Anson Jones functioned as the last president of the Republic of Texas.

Statehood

Population

Intensified migration to Texas after statehood raised the population to about 150,000. Societies such as the Texas Emigration and Land Company now pledged to settle colonists who would agree to constitute a militia for defense against the Indians; in return they would receive a grant of 320 acres of choice land. Most of the newcomers continued to migrate from the states of the lower South; slavery was granted legal protection by the Texas constitution of 1845. The Texas population by 1860 was quite diverse, with large elements of European whites (from the American South), African Americans (mostly slaves brought from the east), Tejanos (Hispanics with Spanish heritage), and about 20,000 recent German immigrants.[5]

- The Germans who settled Texas were diverse in many ways. They included peasant farmers and intellectuals; Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and atheists; Prussians, Saxons, Hessians, and Alsatians; abolitionists and slaveholders; farmers and townsfolk; frugal, honest folk and ax murderers. They differed in dialect, customs, and physical features. A majority had been farmers in Germany, and most arrived seeking economic opportunities. A few dissident intellectuals fleeing the 1848 revolutions in Germany sought political freedom, but few, save perhaps the Wends, went for religious freedom.

- The German settlements in Texas reflected their diversity. Even in the confined area of the Hill Country, each valley offered a different kind of German. The Llano valley had stern, teetotaling German Methodists, who renounced dancing and fraternal organizations; the Pedernales valley had fun-loving, hardworking Lutherans and Catholics who enjoyed drinking and dancing; and the Guadalupe valley had atheist Germans descended from intellectual political refugees. The scattered German ethnic islands were also diverse. These small enclaves included Lindsay in Cooke County, largely Westphalian Catholic; Waka in Ochiltree County, Midwestern Mennonite; Hurnville in Clay County, Russian German Baptist; and Lockett in Wilbarger County, Wendish Lutheran.

Transportation

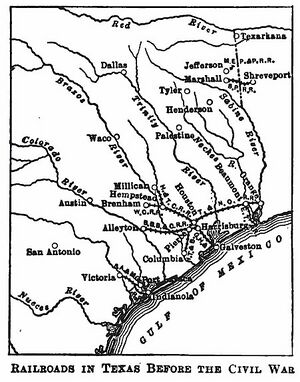

A liberal land grant program encouraged the construction of intrastate railroads, and by 1875 rail connections with many cities outside the state had also been effected. Stagecoach travel was popular, and a number of cities in northern Texas were serviced by the celebrated Butterfield Overland Stage. Some river traffic, particularly freight on the Brazos and Colorado rivers, continued to flourish.

The Texas Rangers were formed during the Republic and continued as state police took an active part. Originally intended by Stephen Austin as a striking force against hostile Indians, the rangers were famous for their ability as horsemen and their courage when greatly outnumbered. Hispanics portray them as brutal and intolerant.

U.S. War with Mexico

Mexico had never tolerated annexation and swore to invade and reconquer the breakaway province, and to go to war with the U.S. if annexation took place. The immediate cause of the Mexican-American War, 1846-48 was a boundary dispute; Mexico insisted that it owned the area south of the Nueces river. There were no battles in Texas, but it was an important staging point for American army movements that invaded and conquered Texas.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in 1848 made the Rio Grande the boundary.

Compromise of 1850

The US acquired New Mexico, but Texas also claimed the Rio Grande to its source, thence north on the meridian to the 42nd parallel, thereby including parts of New Mexico as well as the future states of Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Wyoming. The dispute had national consequences because it involved lands north of 36°30'and was related to the divisive question of slavery in the territories. Congressional debate soon revealed that Texas was willing to compromise if some settlement of its outstanding indebtedness could be realized. The Compromise of 1850 resolved the issue. The Texas debt, of approximately $10 million, was assumed by the United States as compensation for a reduction in the state's boundary claims. The northern limit was placed at the intersection of the 100th meridian and 36°30', thence west to the 103rd meridian, thence south to the 32nd parallel, then following that line to the Rio Grande, and along the channel of that river to the Gulf of Mexico.

Coming of Civil War

In the 1850s, loyalty to the Union or secession became the dominant issue in Texas politics. In the U.S. Senate, Houston was the only southerner to vote against the Kansas Nebraska Act, which repealed the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Believing that slavery had reached its natural limit of expansion and that further agitation would only destroy the Union, Houston defied an angered Texas state legislature. With his career in the Senate stymied, Houston returned to Texas and suffered his only political defeat in 1857 in the gubernatorial contest. But in 1859, campaigning on a platform of loyalty to the Union, he successfully defeated the incumbent governor, Hardin Runnels.

Civil War, 1861-65

In the 1860 presidential election, John Breckinridge, a southern Democrat and proslavery nominee, carried the state. Commenting on Abraham Lincoln's election, Houston urged that Texas remain in the Union until it became the victim of a "federal wrong." The majority of Texans, on the other hand, chose to view Lincoln's victory at the polls as a threat to their slave property and to states' rights. Houston adamantly refused to swear allegiance to the Confederacy and was deposed in 1861 in favor of Lt. Gov. Edward L. Clark. A popular convention endorsed secession, the people ratified it, and Texas officially joined the Confederacy on March 2, 1861.

In the war the state supplied the South with about 60,000 soldiers, most of whom remained in Texas to guard against Union invasions and Indian raids. "Terry's Texas Rangers" (a cavalry unit commanded by Benjamin F. Terry) and John Sibley's brigade, which campaigned in New Mexico, were the best known. There was little fighting within Texas, which served principally as a conduit for supplies from Mexico. Matagorda, Brownsville, and Galveston fell to Union forces, but in a combined military and naval assault Galveston was recaptured by the Confederacy.

German Texans were highly suspect during the war, and a number were executed without trial.

Reconstruction

Slavery ended and Reconstruction began in Texas on June 19, 1865, celebrated by the Freedmen as "Juneteenth". Andrew J. Hamilton, a staunch Unionist before the war, was named provisional governor by President Andrew Johnson, but disruptions and violence were endemic throughout the state. The Reconstruction Act of 1867 shut down the incumbent government, put the state under control of the U.S. Army, and restructured politics.

- The first critical step...was the registration of voters according to guidelines established by Congress and interpreted by Generals Sheridan and Griffin. The Reconstruction Acts called for registering all adult males, white and black, except those who had ever sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States and then engaged in rebellion.… Sheridan interpreted these restrictions stringently, barring from registration not only all pre-1861 officials of state and local governments who had supported the Confederacy but also all city officeholders and even minor functionaries such as sextons of cemeteries. In May Griffin...appointed a three-man board of registrars for each county, making his choices on the advice of known Unionists and local Freedman's Bureau agents. In every county where practicable a freedman served as one of the three registrars.... Final registration amounted to approximately 59,633 whites and 49,479 blacks. It is impossible to say how many whites were rejected or refused to register (estimates vary from 7,500 to 12,000), but blacks, who constituted only about 30 percent of the state's population, were significantly overrepresented at 45 percent of all voters.[6]

The Republican party won the elections of 1869, issued a new state constitution, and elected E. J. Davis as governor. The Republicans were led by native Texans ("Scalawags"), with few Carpetbaggers (northerners). Legislative inexperience was primarily responsible for the passage of many questionable statutes, particularly concerning taxation. Financial irregularities increased; in their spleen at "bottom rail on top" (a reference to the improved status of blacks) some Texans embraced the Ku Klux Klan and other violent informal groups seeking to impede legitimate political gains of former slaves. By 1874 the conservative Democrats, or Redeemers, took power as Richard Coke, was elected governor. Shortly thereafter the last federal troops were withdrawn from military occupation duty.

John L. Haynes (1821-88) was a Texas politician and writer who dissented with many of the typical Southern views of the time. From the late 1850's through the 1880's, Haynes won notoriety as a protector of Mexican Americans, an opponent of secession, a Union army officer, a supporter of freedmen's rights, and a Republican "scalawag." The unifying theme in Haynes's life was his consistent opposition to the dominance of Texas politics and society by a minority of conservative, Democratic, and Anglo planters. He was a Southern dissenter by principle, not merely expedience.[7]

After Reconstruction Texas was a part of the Solid South that nearly always voted for the Democratic nominees.

Gilded Age

The Gilded Age of the 1870s and 1880s generated a major economic boom for the 800,00 people recorded in the 1870 census. Internal railroad construction, made possible by state land bonuses, increased appreciably. By the mid-1870s nearly every major city in Texas had passenger and freight service, and attention turned to interstate and transcontinental railroads. The Missouri, Kansas and Texas (Katy) Railroad, chartered in Kansas, was completed across northern Texas in 1872. In that year the Houston and Texas Central became a part of the gigantic Southern Pacific railway system, the International and Great Northern Railway spanned the state from northeast to southwest, and the Texas and Pacific, building westward, joined the Southern Pacific at a point near El Paso and ran to San Francisco.

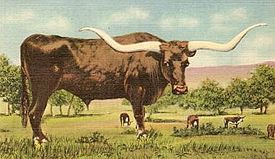

Texas had long had many cattle, but because markets were far and transportation unavailable, they had little value. Many large scale Cattle drives moved herds north to railheads in Kansas. The construction of railroads from Chicago to Kansas put the great Chicago cattle market within reach. The first major cattle drive north to Kansas took place in 1866. For 20 years thereafter, large herds of cattle were driven north along the Chisholm Trail. As the railroads were built across Texas, they ended the long cattle drives. The open range was quickly closed, and the farmers followed the cattlemen west.

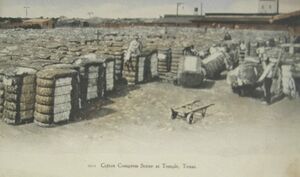

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Texas increased its production and became the leading cotton-growing state in the Union. The cattle industry also made great strides. Range cattle had roamed the Texas Plains since the days of the Spanish explorers, but removal of the Indian barrier in west Texas and improved methods of drilling for subsurface water greatly facilitated the growth of the cattle business. Overland drives brought the cattle to rail points in Kansas, where they were shipped to eastern and mid-western markets. The piney woods area of east Texas continued to sustain the lumber industry. In the Rio Grande Valley citrus fruit production became increasingly important.

Texas was both southern and western, but the south predominated. Most of the original Anglo migrants came from the South; they implanted an agricultural, slave-holding economy and held political control of the state. It started off as frontier, but so too had all of the South. Texas ranching was a mix of south, west and Hispanic. After the close of the frontier around 1890, Texas had more in common with southern cotton farmers than western ranchers and cattlemen.

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in Texas began earlier than most states, with the election of Governor James Stephen Hogg (1851-1906, governor 1891-1895) in 1890 and his reelection in 1892. Hogg was the leading reformer of the era, taking credit for establishing the Texas Railroad Commission, ousting Standard Oil, and passing laws to stop outside monopoly control of Texas oil and other resources was enacted.[9] Hogg was a reformer and an advocate of a strong state government. Policies that he established have continued and are reflected in the railroad commission's supervision of the oil and transportation industries, the attorney general's prosecutions of antitrust activities, and state support of an advanced public education program. Hogg, the regular Democrat, was reelected after an intense contest in 1892, with 44% percent of the vote (190,500) to 31% (133,400) for conservative Jeffersonians Democrat George W. Clark (1841-1918)[10] and 25% (108,500) for Populist Thomas Nugent (1841-95)[11] . Hogg's coalition included white farmers, a few important businessmen who did not object to the Railroad Commission, manual workers in the cities, and a some black voters. Clark had the support of most businessmen, large ranchers in the south and west, and blacks controlled by the Republican Party. Nugent's strength lay white small farmers; he fared poorly among blacks.

Businessman Edward House (1858-1938), was Hogg's campaign manager; behind the scenes House engineered the election of three more protégés as governor--most of them more conservative than Hogg. In 1913 House became the top adviser to President Woodrow Wilson, and brought several Texans to high office.[12] In 1905, progressives passed a law requiring a direct primary in major elections and passed a series of corporate taxes. In 1906, a progressive Democrat, Thomas Campbell, won the governorship, and the legislature responded with an unprecedented outpouring of reforms, including regulation of the insurance industry, state insurance for bank deposits, additional tax reforms, improvements in public education, abolition of the barbarous convict-leasing system, pure food and drug legislation, and several labor safety laws.

Population

Texas reached 4 million population in 1910, making it the fifth largest state, and continued to grow. It remained primarily rural, based on cotton farms[13] and ranches, with 30% living in numerous villages and towns and a few cities.

Galveston, with 17,000 was the largest city in 1870; it recovered from the devastating hurricane of 1900, which killed 6,000 people, and reached 37,000 in 1910. Galveston became nationally famous for its modernized "commission form" of government that stressed efficiency and minimized patronage. The largest city in 1910 was San Antonio at 96,000. Houston (79,000 in 1910) was a rail and oil center; it competed with Dallas (92,000), the banking and merchandising center. Thanks to the meat packing plants that opened in Fort Worth in 1903, it reached 73,000 in 1910. El Paso counted 39,000; Austin, the capital, 30,000; and Waco 26,000. The Model T and other autos began arriving, and along with tractors they started to replace mules and horses on the farm. None of the cities had significant suburbs; instead they built street car systems to bring shoppers to the central business district.

Lynching

Blacks grew in number but declined from 22% of 1890 population in 1890 to 16% in 1920. They were increasingly segregated in public places, and lost the right to vote. Physical intimidation occurred regularly. Of the 468 lynching victims in the state between 1885, the peak, and the last episode in 1942, 339 were black, 77 white, 53 Hispanic, and 1 Indian. [14] Much improved law enforcement after 1920 meant the violence rapidly died out, but segregation only ended in 1964.

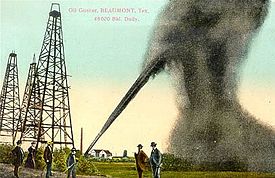

Oil

Joseph S. Cullinan, a Pennsylvania oilman, built the oil industry starting with a well at Corsicana in 1895 that produced more than 800,000 barrels a year at its peak in 1900. It was the gusher at Spindletop, near Beaumont, in 1901 that produced 75,000–100,000 barrels a day and revolutionized the industry. The Spindletop field, pumped 17,500,000 barrels in 1902. Independents and wildcatters competed with major corporations such as Texaco (founded by Cullinan in 1902), Gulf and Humble Oil (now part of Exxon-Mobil).

Plan de San Diego: 1915

In 1911 an extremely bloody decade-long civil war broke out in Mexico. Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled to Texas, raising the Hispanic population from 72,000 in 1900 to 250,000 in 1920. Revolutionaries and radicals came too; tensions between the U.S. and Mexico escalated to an undeclared war, as American armies invaded parts of Mexico. In 1915 a radical manifesto called the "Plan de San Diego" was issued in San Diego, a village in Duval County in south Texas. It called on Hispanics to reconquer the Southwest and kill all the Anglo men. Rebels assassinated opponents and killed several dozen people in attacks on railroads and ranches before the Texas Rangers smashed the insurrection. Tejanos strongly repudiated the Plan and affirmed their American loyalty by founding the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). LULAC, headed by professionals, businessmen and modernizers, became the central Tejano organization promoting civic pride and civil rights.[15]

Politics

n 1915 Governor James E. ("Pa") Ferguson took office, but was ousted in 1917 by impeachment for corruption. This began a long controversy over "Fergusonism," during which the ousted governor's wife was twice elected chief executive, in 1924 and 1932.

Great Depression: 1929-39

East Texas was the nation's largest cotton producer; two million Texans depended on cotton for their livelihood during the hard depression decade.[16] Cotton prices were low, as the world market had collapsed. After 1933 the New Deal cotton programs ordered less cotton to be produced, in order to cause an even higher increase in prices. The New Deal therefore started by plowing up millions of acres of cotton that had already been planted in 1933. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) followed with its voluntary production controls and price-support loans. Cotton growers pressed Congress for mandatory controls, and these were implemented under the Bankhead Cotton Control Act of 1934. When the Supreme Court invalidated the first Agricultural Adjustment Act in 1936, the New Deal replaced it with the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act. This measure was overwhelmed by the 19-million-bale cotton crop of 1937, and after a year of legislative stalemate, Congress passed the second Agricultural Adjustment Act (1938), which incorporated major features of the Ever-Normal Granary Plan. By 1940 cotton prices were high and prosperity had returned for the land owners. However, tenants and sharecroppers, were often denied their share of the benefit payments and, especially after 1935, were forced off the land because of the forced reductions in acreage.[17]

World War II

Civil Rights

AFter 1874 white men in the Democratic party controlled the state and minorities had few rights or opportunities. For example, the Texas legislature approved a poll tax in 1902 and later barred blacks from the Democratic primary. The state passed Jim Crow segregation laws and showed little tolerance for any public roles for African Americans; Mexican Americans were not officially segregated and had the vote. However they had second class status and their votes were controlled by local bosses such as Manuel B. Bravo in Zapata County.[18]streaming into the state. Change occurred, however, when the Supreme Court's Smith v. Allwright decision (1944) voided the state's white Democratic primary.[19]

Even so blacks had little power and remained segregated until the President Lyndon B. Johnson convinced Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1965 in memory of John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. By 1978 the Texas House of Representatives included 14 African Americans and 17 Mexican Americans. In 1980 almost 1,000 Mexican Americans held public office in local government along with 200 blacks. Despite sending prominent liberals to the U.S. Senate after World War II, such as Lyndon B. Johnson and Ralph Yarborough, Texas voters retained their conservative tendencies even during the presidencies of John F. Kennedy and native son Johnson.

Postwar

After 1960 industrialization in Texas was more rapid than in the nation as a whole. Chemical concerns invested heavily in the state, and the electronics and aerospace industries developed tremendously, especially in the Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston areas. In 1964 NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center) in Houston was named headquarters for all U.S. manned spacecraft flights. Construction of a ship channel linking Houston, the U.S. petrochemical center, to the Gulf of Mexico and the advent of the space age combined to make the city one of the fastest-growing in the nation. Houston also became a medical and research center of international fame. Dallas continued to lead in finance, marketing, and insurance activities, while such west Texas cities as Lubbock, Amarillo, and Wichita Falls showed marked economic growth. In 1994 the state reached 18 million population and passed New York for second place, behind California; but it ranked first in cattle, with 14 million.[20]

Politics: move to the GOP

By the 1970s Texas was voting Republican in national election, and after 1990 the GOP started dominating state elections. The first major Republican was Senator John Tower, elected in 1961. The election of Republican William P. Clements in 1978 as governor signaled the rise of a two-party system in state offices. The Democrats, however, reclaimed the governor's mansion in 1982 with the election of Mark White. In 1990 Texas voters elected liberal Democrat, Ann Richards. Under her administration women and minorities were appointed to numerous offices. She was the last Democrat to be elected governor, and was defeated for reelection in 1994. Texans supported Jimmy Carter, a Sunbelt Democrat, for president in 1976 but voted Republican in the next three presidential contests. Indeed, in 1992 Bill Clinton became the first Democrat in the history of the United States to lose Texas and win the presidency. He was opposed by two native sons, incumbent George H.W. Bush and maverick Ross Perot. In 1994 Republican George W. Bush, son of the former president, beat Richards for governor. Meanwhile, Republican Kay Bailey Hutchison in 1993 became the first woman to represent Texas in the U.S. Senate. Her election marked the first time Texas had two Republican senators since 1875. In recent years Texas has become a stronghold for Republicans and a national bastion of economic conservatism.

Further reading

See the longer guide at Texas, history/Bibliography

- The Handbook of Texas Online - Published by the Texas State Historical Association thousands of scholarly articles on every aspect of Texas history

- Barkely, Roy R. and Odintz, Mark F., eds. The Portable Handbook of Texas (2000). 1072 pp. excerpt and text search

- Acosta, Teresa Palomo and Winegarten, Ruthe. Las Tejanas: 300 Years of History. (2003). 436 pp. excerpts and text search

- Barker, Eugene Campbell Charles Shirley Potts, and Charles William Ramsdell. A School History of Texas (1912) 384 pp. Solid textbook by leading scholars of the day online edition

- Calvert, Robert A., Arnoldo De León, and Gregg Cantrell. The History of Texas (2002), 512pp, textbook online edition

- Campbell, Randolph B. Gone to Texas: a History of the Lone Star State (2003), 500 pages. the best scholarly history; online edition

- De Leon, Arnoldo. Mexican Americans in Texas: A Brief History 2nd ed. (1999. online edition

- Fehrenbach, T. R. Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans. (2nd ed 2000). 767 pp. excerpt and text search

- Haley, James L. Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas. (2006). 654 pp. popular excerpt and text search

- Hendrickson Jr., Kenneth E. Chief Executives of Texas: From Stephen F. Austin to John B. Connally, Jr. (1995) online edition

- McDonald, Archie P. Texas: A Compact History. (2007). 256 pp. excerpt and text search

- Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986, (1987). excerpts and text search

- Richardson Rupert N. et al. Texas: The Lone Star State (9th ed. 2004), 450pp; textbook

- Willett, David and Curley, Stephen, eds. Invisible Texans: Women and Minorities in Texas History. (2004). 236 pp.; 18 essays by scholars

notes

- ↑ The Mexican Congress repudiated the treaties.

- ↑ After annexation the ships became the property of the U.S. Navy.

- ↑ Joel H. Silbey, Storm over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War.(2005)

- ↑ Gary Clayton Anderson, The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820-1875. (2005); F. Todd Smith, From Dominance to Disappearance: The Indians of Texas and the Near Southwest, 1786-1859 (2005)

- ↑ from Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ Randolph Campbell, Gone to Texas 2003 p. 276.

- ↑ James Marten, "John L. Haynes: a Southern Dissenter in Texas." Southern Studies 1990 1(3): 257-279. Issn: 0735-8342

- ↑ Donald E. Worcester, "Longhorn cattle," Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ See Robert C. Cotner, James Stephen Hogg: A Biography (1959); Cotner, "Hogg, James Stephen, (1851-1906)" in Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ Doug Johnson, "Clark, George W." in Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ Nugent had 36% in a losing race in 1894. See Worth Robert Miller, "Nugent, Thomas Lewis," in Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ Charles E. Neu, "House, Edward Mandell," Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ Cotton remained king despite the arrival in 1894 of the boll weevil, an insect that ate the unripe bolls and caused a steady drop in yields per acre over the next thirty years.

- ↑ Charges of murder or attempted murder caused 40% percent of the lynchings; rape or attempted rape accounted for 26%. John R. Ross, "Lynching" in Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ Benjamin H. Johnson, Revolution in Texas: how a forgotten rebellion and its bloody suppression turned Mexicans into Americans. (2003).

- ↑ See Ben H. Procter, "Great Depression," Handbook of Texas Online (2008)

- ↑ Keith J. Volanto, Texas, Cotton, and the New Deal (2005)

- ↑ See J. Quezada Gilberto, Border Boss: Manuel B. Bravo and Zapata County (1999)

- ↑ Charles L. Zelden, The Battle for the Black Ballot: Smith v. Allwright and the Defeat of the Texas All-White Primary. (2004). 156 pp.

- ↑ See Sam Roberts, "A Rank That Rankles: New York Slips to No. 3; Now Texas Is 2d Most Populous State," New York Times May 19, 1994