Information management

Although bound up with the tradition of the ‘special library’, information management differs from such earlier concepts in its focus on all kinds of information and a concern for the relationship between information provision and organizational performance. In many special libraries there had long been responsibility for managing internal documentation of various kinds, especially research reports. The history of this development is usefully explored by Black, Muddiman and Plant,[1] who note the emergence of information management concepts following the end of the First World War, with the formal organization of ‘information bureaux’ in the establishment of ASLIB (the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux) in the UK in 1924. Some techniques, however, were even older, witness Kaiser’s work on indexing.[2][3] Indeed, we can date many of the ideas of what is now called ‘information management’ (although ‘documentation’ is used as a near equivalent in much of Europe) to the founding by Otlet and La Fontaine of the International Institute of Bibliography in 1895.[4]

The first use of the terms ‘information management’ or ‘information resource(s) management’ can be dated to the report of the US Commission on Federal Paperwork[5] which drew attention to the costs of handling ‘paperwork’ (which included electronic documents of all kinds) in Federal departments and in other organizations of all kinds in tendering for government research contracts. More recently, the ‘digital revolution’ and the newer Web-based technologies have transformed the handling of information in organizations and made the economic issues more apparent, to the extent that information management is now seen as having a necessary role in the management of organizations.

However, although the original use of the term clearly identified ‘information’ as the content of documents, ‘information management’ has also come to be used in other areas, usually to identify either the management of information technology (e.g., Synott and Gruber[6]) or the management of information systems (e.g., Galliers and Leidner[7]). To resolve this confusion of interests, a definition is needed and that provided for another encyclopedia will serve here:

The application of management principles to the acquisition, organization, control, dissemination and use of information relevant to the effective operation of organizations of all kinds. 'Information' here refers to all types of information of value, whether having their origin inside or outside the organization, including data resources, such as production data; records and files related, for example, to the personnel function; market research data; and competitive intelligence from a wide range of sources. Information management deals with the value, quality, ownership, use and security of information in the context of organizational performance.[8]

The life-cycle of information

The information life-cycle is an appropriate model of information processes with which to begin a consideration of information management. Such life-cycles are well-known in various fields from information systems development (see, for example, the US Department of Justice systems development life cycle[9] to records management (see, for example, Penn[10]) and usually involve some notion of the ‘death’ of a system or the destruction of records, once they have fulfilled their function. The information life-cycle is somewhat different, however, since information begets information in a cyclic process that involves no necessary destruction of the information at any point.

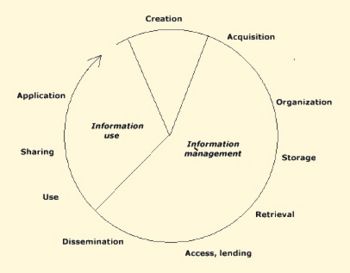

The figure to the right, representing the life-cycle, suggests that there are three distinct areas in the life-cycle: the creation of information, which may be the creative act of an individual, or the by-product of automatic processes (e.g., in the creation of production records in a company); the management of the embodiments of information, such as databases, electronic files and documents; and the use of information.

The creation of information, where it depends upon the actions of the individual is clearly outside the scope of any organizational unit charged with the management of information. However, where the creator makes use of software and networks, such as in the composition of this article, where the only resources used have been electronic resources and where various software systems, such as a word-processor and a Web browser have been employed, then the management of these systems in organizations will be necessary. We define this, however, as ‘information systems management’, rather than information management. Similarly, where the information is generated automatically, or semi-automatically through monitoring various processes, those processes may be carried out by information and communication technologies that can be managed and, indeed, must be managed.

One can also easily imagine a situation in which the information management unit of an organization is charged with the physical (or electronic) production of internal reports of one kind or another and, thus, must be involved in the process of creation of these documents. The sector of the diagram labelled information management covers those activities that are common to, for example, libraries managing published documents, and information systems departments managing databases–the same operations have to be designed in either case. The term content management is also applied to these activities.

The information use sector of the life-cycle is the province of the recipients of information, whether they have deliberately sought the information from the organized physical or electronic storage areas, or have received it as a result of a dissemination process based upon their needs, as understood by the system. The question for information management in relation to this sector is, "To what extent is it possible to manage the processes of information use, sharing and application so that information has a more significant impact on the performance of the organization?" This question will be considered later in this article.

The scope of information management

Although the scope of information management may be determined from the figure, there is also other work that does so more specifically. Choo,[11] for example, has produced a variant of the life-cycle based on the idea of an ‘information value chain’, proposing a range of activities:

- identifying information needs;

- assessing the relationship of sources to needs and acquiring those resources;

- organization and storage of the information;

- design and development of information products;

- distribution of information, either formally or informally; and

- information use.

Kirk[12] has suggested that alternative definitions of information management can be related to Braman's[13] definitions of information as being a resource, a commodity, the perception of pattern, or a ‘constitutive force’ (i.e., having the power to affect other phenomena).

Becoming more specific still, Macevičiūtė and Wilson[14] show, through an analysis of papers in six key information management journals, that the field is rather diffuse; a term association visualization of the data revealed twenty groups, some of which contained only one or two papers, the largest groups being concerned with information systems development aspects of information management, information systems modelling, health information management, user services development, and medical patients’ databases.

In a brief survey for this article, an analysis of 130 news items on information management, drawn from Google's alert service on the subject, showed that top ten topics of interest to the information industry were, in rank order: 1-content or document management systems; 2-health information management; 3-security information systems; 4-financial information systems; 5-master data management; 6-business intelligence systems; 7-customer relationship management systems; 8-legal information systems; 9-mobile information systems; and 10-records management systems. This results in what might be called a product area categorisation of content, as distinct from the more theoretical perspectives of Choo and Macevičiūtė and Wilson.

Regardless of the nature of the analysis, however, it can be seen that, although the concept of ‘information management’ originated in the era before the ubiquitous use of computers, the topic is now firmly associated with information technology. Information is generated through the use of computer systems (as this essay is), much information is available only in digital form (increasingly through Web-based technologies), information systems are computer-based systems, and information is disseminated to and shared by users largely through the use of computer networks.

Consequently, we are increasingly seeing a team approach to the management of information in organizations, with two strands: the technology strand and the information content strand.

The intellectual tools

We cannot, however, allow the nature of information management to be defined solely by reference to the machine: the intellectual tools used in the management of information are probably of greater significance.

Here, we can bring together notions from the different life-cycles described above and attempt a categorisation of intellectual (and other) tools that are employed in information management.

Information needs analysis

The obvious starting point is that to which Choo draws attention, i.e., the need to carry out some kind of information needs analysis, so the acquisition, organization and dissemination of information may be based on some understanding of the organizational and personal goals of the target audience. The theoretical aspects of this stage in the cycle deserve an article of their own and will not be dealt with here. Rather, some observations on the practice of information needs analysis will be offered. Work of this kind goes on more or less automatically in any unit that is serving the members of an organization through casual conversation and observation of the expressed needs for information and, by these means, the information manager acquires at least a partial understanding of what kinds of information are needed. However, this partial understanding needs to be bolstered by the occasional more systematic exploration of needs, for example, by carrying out occasional surveys and by using feedback questionnaires to follow up the provision of information, either generally, or in relation to specific areas that may be perceived as problematical in one way or another.

The information manager also needs to distinguish between the personal information needs of those working in the organization and the information needs of the organization itself. Wilson,[15] Loughridge, Greene and Wilson[16] and Huotari and Wilson[17] have explored the idea of critical success factors as a means of determining the information needs of organizations, in relation to business in general, to university departments and to Finnish corporations. These studies reveal the significance of the information management function in organizations – a function that is often ignored in the literature of business management.

Information acquisition

When we turn to the intellectual operations that correspond to the life-cycle stages, the situation becomes more complex, since the operations are often integrated and the techniques seek to satisfy the needs of more than one stage of the life-cycle. Bearing this in mind, however, we can broadly distinguish between two sets of information that need to be acquired: information created in the organization itself, and information from external sources.

Today, much of the internal information in organizations is created originally in electronic formats, in the shape of e-mail messages, database entries, spreadsheet, word-processed documents and all of the other products of the electronic office. In addition, much information relating to production and sales is generated more or less automatically as those engaged in these activities carry out their tasks. For example, computer-controlled production machines will generate a data flow that reports many parameters of the production process, and sales data, entered into spreadsheets or databases will be analysed by macros that report trends, regional differences and other information of relevance to management.

In many cases, the management of internal information of these kinds will be controlled not by an information manager but by staff in the appropriate departments of the organization. However, the concept of business intelligence has led to the emergence of systems, the aim of which is to aggregate, analyse and report on the significance to management of these different information sets.

The term business intelligence was used as early as 1958, by H.P. Luhn in a classic paper entitled A business intelligence system. It is clear from the paper, as this abstract shows, that what was envisaged was, in fact, a complete information management system:

An automatic system is being developed to disseminate information to the various sections of any industrial, scientific or government organization. This intelligence system will utilize data-processing machines for auto-abstracting and auto-encoding of documents and for creating interest profiles for each of the "action points" in an organization. Both incoming and internally generated documents are automatically abstracted, characterized by a word pattern, and sent automatically to appropriate action points. This paper shows the flexibility of such a system in identifying known information, in finding who needs to know it and in disseminating it efficiently either in abstract form or as a complete document.[18]

It is interesting to reflect that today, some fifty years and billions of dollars worth of research later, no such system exists.

In its origins, then, business intelligence was a fluid concept, embracing what is now the whole of information management. Today, the situation is similarly fluid, with the concept being used as a synonym for competitive intelligence[19] and environmental scanning[20] and being associated with processing internal data[21] with artificial intelligence and expert systems[22] and with the similarly fluid concept of knowledge management.[23]

We have to conclude, therefore, that the concept, as it stands, has no clear, distinctive definition and this conclusion is supported by the definition offered by the TechWeb TechEncyclopedia:

Any information that pertains to the history, current status or future projections of an organization.[24]

Similarly, business intelligence software is a broad concept for a variety of software systems. Again, TechWeb offers an interesting comment:

Business intelligence was the 1990s buzzword for the management information system (MIS) of the 1970s and the decision support system (DSS) and executive information system (EIS) of the 1980s. MIS implementations often failed because the hardware was too slow and the software was not sophisticated. Countless DSS, EIS and OLAP tools followed, which added functionality, but were often point solutions to the problem. BI implies yet more integration and ease of use (of course, no matter what the subject, every new approach in the information field is touted as the one providing more integration and greater ease of use).[25]

If we accept that business intelligence is, as TechWeb notes, any information relating to any aspect of the business, past, present or future, then we can more carefully distinguish between environmental scanning and competitive intelligence, although, again, these terms are often used interchangeably. We can distinguish between the two quite readily, however: environmental scanning relates to the acquisition of information on the business environment as a whole, taking account not only of the actions of competitors, but also of political, social, legal and economic issues and trends that might affect the future of the business. Competitive intelligence, on the other hand, involves the acquisition of information on the competitive environment, per se, with a focus on the strategies, policies and market activities of competing businesses. Both of these functions have a considerable body of literature, not always as finely distinguished as in the definitions above, for which useful starting points are Bergeron and Hiller[26] and Choo and Auster.[27]

Today, as far as business intelligence is concerned and certainly for many other kinds of information, acquisition of the physical containers of information–books, reports, journals, patents, government information, etc.–has been replaced by electronic access to such resources. Much of the information required is freely available through the use of search engines, scanning the World Wide Web, and a great deal is available as subscription services, especially in relation to scientific, medical, technical, financial and legal information. The problems created by the costs of subscription contracts for libraries is well known as are the efforts to reduce these costs for the developing world[28] For many university libraries, subscription costs for electronic resources has threatened the viability of the book acquisition budget[29][30] This issue is responsible, to a significant degree, for driving the ‘Open Access’ movement.[31]

Information mapping or auditing

As well as acquiring information on a systematic basis from inside and outside the organization, the information manager needs to know what information resources exist throughout the organization. The discovery of these resources is known as information mapping.[32] The term information auditing[33][34] is also applied, to draw attention to the money value of those resources.

By extension we can include an organization’s intellectual property and intangible assets in the mapping process, although this is not usually done under the information mapping rubric. There is a degree of overlap of these two terms and no clear distinction appears to exist: we could define intangible assets as the generic term, to cover all assets that have no physical existence, but which have real value to the organization, such as brands, goodwill, designs, logos, etc., and retain intellectual property for those intangible assets over which the organization has a legal right, such as trade marks, patents, copyrights, registered industrial processes and so on. The distinction, however, is hard to retain and many writers use the terms interchangeably. The term intellectual capital is also applied to both intangible assets and intellectual property, and all are sometimes referred to as invisible assets.

Sullivan[35] sets out a brief history of the intellectual capital idea, crediting the Japanese researcher Hiroyuki Itami[36] with the origin of the term and pointing to the work of more recent authors in popularising the concept.[37][38][39][40][41][35]

The notion of information mapping is also applied to the identification and recording of the personal expertise of organizational members. This idea appears to have originated in the 1960s in the personnel management sector with the creation of indexes to expertise or skills inventories[42][43] and has continued to the present day under these names, generally outside the information management function. However, the application of computer systems brings the function within the purview of the information systems department, if not the information management function. More recently, without reference to the existing history of the concept, the proponents of knowledge management have coined the term knowledge mapping to define exactly the same function, apparently without knowledge of the earlier usage.[44]

Information organization

Traditionally, in the library setting, the organization of information meant cataloguing, classification and, mainly in the special library context, indexing (the area is often referred to as knowledge organization, but that term is ambiguous, since it ought properly to refer to the problems of individual learning and understanding, rather than to the organization of information products and/or their surrogates). And, of course, these techniques continue to be widely employed today, whenever the organization of the physical container of information is necessary. Thus, books continue to be catalogued and classified before they are placed on the library shelf. Electronic resources offer possibilities for different approaches, however, although the tools of classification and cataloguing may continue to be employed in that context.

The exposure of the problem of organizing information to the computer science community has resulted in part in a re-invention of library concepts, so that, for example, classification schemes have become taxonomies or, rather less appropriately, ontologies (a word which w'uld actually mean not classification but alternative theories of being) and faceted classification has been either re-invented or used without awareness of its origins, although more are now aware of Ranganathan’s contribution (see, e.g., Prieto-Diaz[45] and Uddin and Janacek[46]). Cataloguing has become meta-data tags on Web pages, and indexing, in its latest manifestation, has become tagging on social bookmark Websites.[47][48]

Weinberger[49] has proposed that social tagging by many different people can result in social taxonomies, which will overcome the lack of structure in the Web because the resulting multiple retrieval points can be used to bring together what structure of any kind would otherwise disperse. The validity of this view is yet to be proved and the formal equivalent of this process, that is, the full text searching of entire document files, is not always satisfactory and has resulted in the attention devoted to taxonomies and meta-data in the literature on computer-based information handling. The notion of the Semantic Web[50] is based on the proposition that if the structure of electronic documents on the Web can be made explicit, it will be possible to make inferences from the structure as to the ‘meaning’ of the document. This may well be true for certain restricted fields of discourse, but, to date, progress towards the Semantic Web has been slow.

Whatever the changes, however, the problems remain the same: how to uniquely identify an element of information (whether that element is a book, a Web page, or an e-mail message), and how to identify the subject content. Some of the problems of managing physical information resources disappear when the form is electronic: thus, a book can be in only one place on the shelf, but an electronic document can be filed in many places, if the subject content requires it, or it may be filed in only one place, and be found not by searching the file structures, but by using a search engine, which scans the full text of the document.

At the level of Websites, the notion of information architecture has come to play a significant role in organizing and structuring information resources. As is often the case with developments in the world of computing, the terminology is somewhat misleading, since the aim of information architecture is to structure a Website, so that its contents may be easily navigated and discovered. Richard Saul Wurman is credited with having coined the term 'information architecture' at the American Institute of Architecture conference in 1976,[51] but the term information architecture came to more general notice through the publication of the book by Morville and Rosenfeld in 1988.[52] The definition by Morville and Rosenfeld is worth quoting in full, because it reveals the complexity of the concept:

in•for•ma•tion ar•chi•tec•ture n.

1. The structural design of shared information environments.

2. The combination of organization, labeling, search, and navigation systems within web sites and intranets.

3. The art and science of shaping information products and experiences to support usability and findability.

4. An emerging discipline and community of practice focused on bringing principles of design and architecture to the digital landscape.[52]

Document management systems are closely allied to information architecture, since they are the software systems used to create and organize electronic content on Websites and intranets.[53][54] The terms content management systems and enterprise content management systems are also closely related. Document management systems embody all of the elements of the capture (e.g., images of documents may be included), organization, version control, indexing, meta-tagging, workflow control and publication to a Website or intranet of electronic documents. Numerous document management products exist among which some of the more widely used are Xerox DocuShare, Xythos Enterprise Document Management Suite and Micosoft's Sharepoint.

Information access & retrieval

As with the storage and organization of information, access and retrieval relate directly to the form in which it is kept. Access to physical objects, such as books and back files of paper journals, filing cabinets full of print reports, etc. is becoming less of a day-to-day event, as electronic documents dominate, but, in the case of archives, continues to be necessary. In this case, traditional methods prevail for the physical management, e.g., shelf classification, while retrieval is often achieved through computer-based catalogues.

Access to and retrieval from electronic document systems, digital libraries, etc., has now become a matter of Web-based systems, with intranets and subject portals and search engines. In some cases, specialised information retrieval systems are employed, rather than enterprise versions of search engines such as Google, but we might expect the differences between an IR system and a search engine to continue to disappear.

In most cases, the information user will be presented with a Web interface to whatever document collections he or she needs access and will be unaware of the underlying technology and systems. Exceptions occur for specialised systems for the interrogation of databases, but even these are now being integrated with intranets in organizations. In other words, the trend is towards the use of intranets as the basic mode of information delivery.[55][56][57]

Dissemination

Means for the dissemination of information have been evolved in special and academic libraries for decades: traditionally, methods such as the distribution of photocopied journal contents pages, circulation of journals and the production of current awareness bulletins were employed. Today, however, with the spread of computer networks inside and outside organizations, these methods have been replaced by electronic alerting services and the electronic distribution either of the documents themselves or of notices of their existence.

Many publishers of medical, scientific and technical publications now have alerting services, through which one may receive e-mail alerts on the publication of new books in one’s field or of newly-published journal papers. Elsevier's personalization/ Science Direct ‘personalization and alerting services’ are typical in providing alerts on new journal papers and books from a pre-defined list, new items on specific topics and new occurrences of the citation of a specific paper. Alerting services are also provided by libraries and other third-parties: for example, the National Library of Medicine in the USA has thirty clinical alerts and seven ‘clinical advisories’ in areas as diverse as HIV/AIDS, and diet and exercise. How such services are used has been explored, for example, by Björk and Turk[58] and by Fourie.[59]

Weblogs, or blogs, are also becoming a common means of distributing news of all kinds. They are much used in the computer industry, for example, where the major manufacturers have Weblogs written by staff members. Microsoft has a number of these, including the blog of the Office Business Applications Team, the Windows XP Embedded Team, and the Microsoft Office Project 2007. There are, of course, also unofficial Weblogs, such as Chris's unofficial Office Live developer blog at Microsoft and the Unofficial Google Weblog. As these appear on the Websites of the companies, however, it is not clear how unofficial they may be.

The virtual ubiquity of electronic documents in organizations today means that internal reports and other publications can be readily circulated to organizational members. One of the problems here is that users tend to opt into mailing lists and, as a result, receive more information than they need or can cope with. Consequently, the subject of information overload has become significant for organizations (see Edmunds and Morris[60] Allen and Wilson[61] and, from a different perspective, Olsen, Sochats and Williams[62]).

Information use

As noted in the life-cycle diagram, information use covers all of those activities that occur once information has been received by the user. It may be used by the individual to add to or confirm their own knowledge, it may be shared with others in a team or across the organization, it may be applied to the solution of a current problem, and it may be used in the creation of new ideas and subsequent new information outputs.

Very little of this can be under the control of an information management or information systems department in an organization, since they involve issues of general management, team-building, reward systems in the organization and other human resources and human relations issues outside the scope of this article.

However, there are two areas where the provision of information handling tools may be of help. The first is the area of personal information management (PIM), a phrase usually associated with the maintenance of contact lists, timetables and diaries, personal expenses and other such everyday information needs. The term can be expanded, however, to include personal information searching and the retention of documents in personal files. PIM has come to be associated with the PDA (personal digital assistant) and its ability, particularly since the announcement of the Palm Pilot in 1996, but synchronisation with the desktop computer was a key design criterion of the Palm[63] acknowledging that people had been using PCs for their personal information management for some time.

Research into personal information management is relatively sparse, since most informations systems research is focussed upon company-wide systems initiatives, rather than on individual needs[64] but the subject is attracting increasing interest, perhaps in part because of the integration of the PDA and the mobile phone. Topics such as the personal management of e-mail[65] the retention of information[66][67] and personal information collections in general[68] are gaining interest from the research community.

We can regard groupware as somewhat akin to personal information management since, to a significant degree it involves coordinating the personal information behaviour of many individuals. This may be done through, for example, corporate, group or team calendars for the coordination of meetings, group contact lists, and shared document or spreadsheet use, or shared, interactive project management systems. The management of versions of documents is critical in groupware systems, along with the ability of different individuals to work on the same document at the same time, without conflict within the system (see, for example, Ellis & Gibbs[33] Li & Li[69]).

Destruction or retention

The life-cycle diagram ought to have a spur reaching out from a point adjacent to dissemination to identify the need to evaluate information resources to determine whether they should be retained in an archive or destroyed. This is a characteristic process in records management and, regardless of constantly reducing cost of computer storage, needs to be taken into account for all kinds of information resources. All too often, however, there is no organizational policy on how and when information should be disposed of, although privacy, data protection and freedom of information legislation have an effect on these matters.[70][71][72]

To some extent the legislative issues work against the retention of information; for example, the destruction of records and of e-mail files may be undertaken not because the information no longer has value, but because the availability of such information to the courts could be prejudicial to particular individuals (see, e.g., Shipley and Schwalbe[73]).

The value of information

The value of information was referred to in the definition of information management quoted earlier and the economics of information deals with this topic. Briefly, however, in the context of information management, the value of information lies in its contribution to organizational performance. However, although this is simple to express, it is extremely difficult to determine. The main reason for the difficulty is that information has value in two senses: its exchange value, or what we have to pay for an item of information, and its use value, or the economic advantage we are able to derive from having the information.[74][75]

The exchange value of information is determined by the economics of the market and the laws of supply and demand. Thus, we are happy to pay a specific sum for a daily newspaper, but, with each price rise, we are likely to assess what value we derive from having the newspaper and, at some point, may decide that the derived value is not enough to justify the cost. In the context of information management, the exchange value of information has been shown to be of relevance in the way university libraries have evaluated journals as subscription costs have risen. University departments and faculty members have been asked to review specific titles to determine whether or not to cancel them as costs have spiralled beyond the libraries’ ability to pay.

The use value of information is more problematic, since, by definition, we can only know this value when the information has been put to use and some economic advantage has been derived. The use value, therefore, cannot be determined in advance. Hence, the paradox that organizations acquire information resources, at some cost, without knowing whether or not those resources are going to be of value to them. In other words, the potential value of information, in many situations, is taken on trust. Companies in the pharmaceutical industry, for example, will pay significant amounts of money for the key journals in their area because they believe that the information on current research may assist their own research efforts in developing new drugs. Similarly, computer companies (which are chiefly assembly plants) will invest in acquiring information on potential sources for, and prices of components such as disc drives, cooling fans, and microchips because such information is crucial in producing the low-cost consumer products that personal computers have now become. The belief is that the cost of acquiring this information and organizing it in corporate databases will bring benefits in lower-cost products that gain a market advantage.

Information strategy

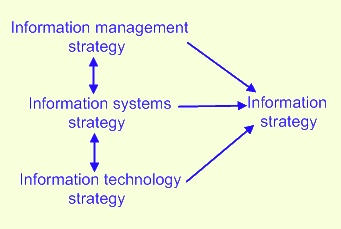

It is now generally recognized that, if an organization is to benefit from its investment in information resources, systems and services, it needs an information strategy. An information strategy sets out a plan for the way information will be acquired by the organization, and how the various processes set out in the life-cycle will be accomplished. Such a plan ought to be based upon a solid understanding of how information contributes to the objectives of the organization and the work tasks of its members and will need to deal with the technological issues as well as with the information issues. The relationship between strategies is shown in Figure 2:

The figure suggests that an information strategy is a composite of strategies for the management of information (as defined in this article), for the development of information systems through which the information is managed, and for the underlying technological infrastructure upon which the systems are built.

Because of difficulties with the definition of ‘information management’ mentioned at the beginning of this article, information strategies sometimes relate only to the technology, or only to the information systems. However, unless the associations are understood and dealt with in a comprehensive strategy, there is always a danger that lack of co-ordination will prevent the full achievement of the organization’s intentions.

Conclusion

An encyclopedia article can only touch upon the main elements of information management. Today, it is a matter of critical importance for organizations that they manage access to and use of information in a cost-effective manner. Given the volume of information processed in organizations, not only by the formal systems established for the purpose, but also by individuals who perform information tasks constantly in their work, effective information management is becoming a more and more significant area for policy development and planning.

References

- ↑ Black, A., Muddiman, D. and Plant, H. (2007) The early information society: information management in Britain before the computer. London: Ashgate.

- ↑ Kaiser, J. (1908) The card system in the office. London: McCorquodale and Co.

- ↑ Kaiser, J. (1911) Systematic indexing. London: John Gibson.

- ↑ Rayward, W.B. (1975) The universe of information: the work of Paul Otlet for documentation and international organisation. Moscow: International Federation for Documentation. (FID 520) Available https://archive.ugent.be/retrieve/2272/otlet-universeofinformation.pdf Accessed 17 July, 2008

- ↑ U.S. Commission on Federal Paperwork (1977) Information resources management. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office

- ↑ Synott, W.R. and Gruber, W.H. (1981) Information Resource Management: Opportunities and Strategies for the 1980s. New York, NY: Wiley.

- ↑ Galliers, R. and Leidner, D.E. (2004) Strategic Information Management: Challenges and Strategies in Managing Information Systems. New York, NY: Wiley.

- ↑ Wilson, T.D. (2003) Information management, In John Feather and Paul Sturges, (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Information and Library Science. (pp. 263-278) London: Routledge.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Justice. (2003) The Department of Justice Systems Development Life Cycle Guidance Document. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Justice Management Division. Retrieved 4 April, 2007 from http://www.usdoj.gov/jmd/irm/lifecycle/table.htm Accessed 17 July, 2008 (Archived at WebCite.org http://www.webcitation.org/5NqXrpKiW)

- ↑ Penn, I.A. (1983) Understanding the life cycle concept of records management. Records Management Quarterly, 17(3), 5-8, 41.

- ↑ Choo, C.W. (2002) Information Management for the Intelligent Organization. 3rd ed. Medford, NJ: Information Today Inc.

- ↑ Kirk, J. (2005) Information in organizations: directions for information management. In, E. Macevičiūtė and T.D. Wilson, (Eds.) Introducing information management: an Information Research reader. (pp. 3-17) London: Facet Publishing.

- ↑ Braman, S. (1989) Defining information: an approach for policy makers. Telecommunication Policy, 13(3), 233-242

- ↑ Macevičiūtė, E. and Wilson, T.D. (2005) The development of the information management research area. In, E. Macevičiūtė and T.D. Wilson, (Eds.) Introducing information management: an Information Research reader. (pp. 18-30) London: Facet Publishing.

- ↑ Wilson, T.D. (1994) Tools for the analysis of business information needs. Aslib Proceedings, 46(1), 19-23.

- ↑ Loughridge, B., Greene, F. & Wilson, T.D. (1996) The management information needs of academic Heads of Department: a critical success factors approach. London: British Library Research and Development Department (BLRDD Report No. 6252) Available http://informationr.net/tdw/publ/hodsin/ Accessed 30 April, 2007.

- ↑ Huotari, M-L. and Wilson, T.D. (2001) Determining organizational information needs: the Critical Success Factors approach. Information Research, 6(3), paper 108. Available http://www.shef.ac.uk/~is/publications/infres/paper108.html Accessed 30 April, 2007.

- ↑ Luhn, H.P. (1958) A business intelligence system. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 2(4), 314-319 (p. 314)

- ↑ Vella, C.M. and McGonagle, J.J. (1999) The Internet age of competitive intelligence. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ↑ Pawar B.S. and Sharda R. (1997) Obtaining business intelligence on the Internet. Long Range Planning, 30(1), 9-10, 110

- ↑ Dhar, V. and Stein, R. (1997) Seven methods for transforming corporate data into business intelligence. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Harmon, P. and King, D. (1985) Expert systems: artificial intelligence in business. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- ↑ Cody, W.F., Kreulen, J.T., Krishna, V. and Spangler, W.S. (2002) The integration of business intelligence and knowledge management. IBM Systems Journal, 41(4), 697-713. Retrieved May 19, 2007 from http://researchweb.watson.ibm.com/journal/sj/414/cody.html Accessed 19 May, 2007. (Archived at WebCite http://www.webcitation.org/5OxWpsmZF)

- ↑ Business intelligence. (2007) In TechEncyclopedia Available http://www.techweb.com/encyclopedia/defineterm.jhtml?term=business%20intelligence Accessed 17 July, 2008 (Archived at WebCite http://www.webcitation.org/5OxYNzCkE).

- ↑ BI software. (2007) TechEncyclopedia. Available http://www.techweb.com/encyclopedia/defineterm.jhtml?term=BIsoftware Accessed 17 July, 2008. (Archived at WebCite http://www.webcitation.org/5OxY6jf70)

- ↑ Bergeron, P. and Hiller, C.A. (2002) Competitive intelligence. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 36, 353-390

- ↑ Choo, C.W. and Auster, E. (1993) Environmental scanning: acquisition and use of information by managers. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 28, 279-314.

- ↑ Feret, B. and Kay, M. (2001) eIFL - electronic information for libraries, a global initiative of the SOROS Foundation’s network. Paper presented at the 67th IFLA Council and General Conference, August 16-25, 2001. Available http://www.ifla.org.sg/IV/ifla67/papers/117-141e.pdf Accessed 19 May, 2007 (Archived at WebCite http://www.webcitation.org/5OxYNzCkE)

- ↑ Cummings, A.M., Witte, M.L., Bowen, W.G., Lazarus, L.O. and Ekman, R.H. (1992) University libraries and scholarly communication. A study prepared for the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Chapter 6, Book and serial pricing. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Available http://etext.virginia.edu/subjects/mellon/ch6.html Access 19 May 2007. (Archived at WebCite.org http://www.webcitation.org/5OxczFoJa)

- ↑ Griebel, R. (1995) German university library budgets – model and reality. Library Management, 16(7), 3-8

- ↑ Suber, P. (2006) Open access overview. Focusing on open access to peer-reviewed research articles and their preprints. Available from http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/overview.htm Accessed 19 May, 2007. (Archived at WebCite http://www.webcitation.org/5OxdIlAfB)

- ↑ Burk, C.F. and Horton, F.W. (1988) InfoMap: a complete guide to discovering your information resources. London: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Ellis, D., Barker, R., Potter, S. and Pridgeon C. (1993) Information audits, communication audits an information mapping : a review and survey. International Journal of Information Management, 13(2), 134-151. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Ellis" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Henczel, S. (2001) The information audit: a practical guide. Munich: K.G. Saur.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Sullivan, P.H. (1998) Profiting from intellectual capital: extracting value from innovation. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons., Inc.

- ↑ Itami, H. (1980, 1987) Mobilizing invisible assets. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Originally published in Japanese, 1980

- ↑ Sveiby, K-E. and Lloyd, T. (1987) Managing know-how. London: Bloomsbury.

- ↑ Sveiby, K-E. (1989) The invisible balance-sheet. Stockholm: Ledarskap.

- ↑ Stewart, T.A. (1991) Now capital means brains, not just bucks. Fortune, 123(1), .31-32

- ↑ Stewart, T.A. (1999) Intellectual capital: the new wealth of organizations. New York, NY: Bantam Dell Publishing Group

- ↑ Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M.S. (1997) Intellectual capital: realizing your company's true value by finding its hidden brainpower. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

- ↑ Bronstein, R.J. (1965) Setting up a skills inventory: how to do it on a shoestring. Personnel, (March/April), 66-67

- ↑ Canada. Treasury Board. Secretariat. (1994) Employee skills inventories for the Federal public service. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada.

- ↑ Vail, E.F. (1999) Knowledge mapping: getting started with knowledge management. Information systems management,16(4), 16-23

- ↑ Prieto-Diaz, R. (1991) Implementing faceted classification for software reuse. Communications of the ACM, 34(5), 88-97.

- ↑ Uddin, M.N. and Janacek, P. (2007) Faceted classification in web information architecture: a framework for using semantic web tools. The Electronic Library, 25(2), 219-233.

- ↑ Hammond, T., Hannay, T., Lund, B. and Scott, J. (2005) Social bookmarking tools (I): a general overview. D-Lib Magazine, 11(4) Available http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april05/hammond/04hammond.html Accessed 8 June, 2007

- ↑ Lund, B., Hammond, T., Hannay, T. and Flack, M. (2005) Social bookmarking tools (II): a case study – Connotea. D-Lib Magazine, 11(4) Available http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april05/lund/04lund.html Accessed 8 June, 2007.

- ↑ Weinberger, D. (2007) Everything is miscellaneous: the power of the new digital disorder. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company

- ↑ Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J. and Lassila, O. (2001) The Semantic Web: a new form of Web content that is meaningful to computers will unleash a revolution of new possibilities. Scientific American, 284(5), 28-37.

- ↑ Resmini, Andrea; Luca Rosati (Fall 2011). "A Brief History of Information Architecture". Journal of Information Architecture 3 (2): 33. ISSN 1903-7260. Retrieved on 21 October 2013.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Morvill, P. and Rosenfeld, L. (2007) Information architecture for the World Wide Web. 3rd. ed. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly.

- ↑ White, M. (2005) The content management handbook. London: Facet Publishing

- ↑ White, M. (2006) Selecting and implementing content management software for intranets and Web sites. Legal Information Management, 6(3), 202-207

- ↑ Bernard, R. (1997) The corporate intranet. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Scott, J.E. (1998) Organizational knowledge and the intranet. Decision Support Systems, 23(1), 3-17.

- ↑ Vaast, E. (2001) Intranets in French firms: evolutions and revolutions. Information Research, 6(4), paper 109. Available http://InformationR.net/ir/6-4/paper109.html Accessed 18 July, 2007

- ↑ Björk, B-C. and Turk, Z. (2000) How scientists retrieve publications: an empirical study of how the Internet is overtaking paper media. Journal of Electronic Publishing, 6(2) Available http://www.press.umich.edu/jep/06-02/bjork.html Accessed 18 July, 2008.

- ↑ Fourie, I. (1999) Empowering users – current awareness on the Internet. The Electronic Library, 17(6), 379-388.

- ↑ Edmunds, A. and Morris, A. (2000) The problem of information overload in business organizations: a review of the literature. International Journal of Information Management, 20(1), 17-28.

- ↑ Allen, D. and Wilson, T.D. (2003) Information overload: context and causes. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 4, 31-44.

- ↑ Olsen, K.A., Sochats, K.M. and Williams, J.G. (1998) Full-text searching and information overload. The International Information and Library Review, 30(2), 105-122.

- ↑ Moggridge, B. (2007) Designing interactions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- ↑ Whittaker, S., Terveen, L., and Nardi, B. (2000) Let's stop pushing the envelope and start addressing it: a reference task agenda for HCI. Human Computer Interaction, 15(2/3), 75-106.

- ↑ Whittaker, S. & Sidner, C. (1996) Email overload: exploring personal information management of email. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems: common ground. (pp. 276-283) New York, NY: ACM Press

- ↑ Jones, W. (2004) Finders, keepers? The present and future perfect in support of personal information management. First Monday, 9(3) Available http://ftp.firstmonday.dk/www/issues/issue9_3/jones/index.htmlm Accessed 18 July, 2008.

- ↑ Bruce, H., Jones, W. & Dumais, S. (2004) Information behaviour that keeps found things found. Information Research, 10(1) paper 207. Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://InformationR.net/ir/10-1/paper207.html

- ↑ Bruce, H. (2005) Personal, anticipated information need. Information Research, 10(3) paper 232 Available http://InformationR.net/ir/10-3/paper232.html Accessed 19 July, 2008

- ↑ Li, R. & Li, D. (2005) Commutativity-based concurrency control in groupware. In, International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing, 2005. (10 pp.) Piscataway, NJ: IEEE

- ↑ Atherton, J. (1985/1986) From life cycle to continuum. some thoughts on the records management–archives relationship. Archivaria, No. 21, 43-51.

- ↑ Caudle, S.L., Gorr, W.L. & Newcomer, K.E. (1991) Key information systems management issues for the public sector. MIS Quarterly, 15(2), 171-188.

- ↑ Barata, K. (2004) Archives in the digital age. Journal of the Society of Archivists, 25(1), 63-70.

- ↑ Shipley, D. and Schwalbe, W. (2007) Send; the how, why, when and when not of email. London: Canongate

- ↑ Repo, A.J. (1987) Economics of information. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 22, 3-35

- ↑ Taylor, R.S. (1994) The value-added information system. Washington, DC: Ablex.